The scarcity of sustainability: unintended asset allocation risks in sustainable model portfolios

Adam Hetts and Sabrina Denis from the Portfolio Construction and Strategy Team examine whether unintended risks are introduced by a shift to ‘sustainable’ investing and the scarcity of allocation options.

Key Takeaways

- There is an inconsistency of risk profiles between traditional and sustainable model portfolios. This is arguably because the asset management industry’s product offering is still catching up to advisor demand for sustainable investment solutions.

- Differences based on more limited sustainable investment availability are not just attributed to regions but can also be influenced by a style and sector tilt, all of which can have an impact on returns.

- These are important considerations for advisors in maintaining asset allocation risk consistency across model portfolios and finding a sustainable method to accomplish clients’ sustainable investing goals.

Sustainable investment considerations are currently a major catalyst shifting the investment landscape. They carry myriad, intended influences on one’s asset allocation including the application of a forward-looking view accounting for the varied impact of climate change across global asset classes and sectors. However, what if this relatively new investment landscape is also creating the potential for other, unintended, asset allocation risks? What if many of the new sustainable model portfolios that advisers are building as a service to their clients are actually unrecognisable to their traditional models when it comes to regional biases, style drifts, and sector concentrations? What are these unintended risks introduced by a shift to ‘sustainable’ investing?

At Janus Henderson, our Portfolio Construction and Strategy (PCS) Team sees this risk dilemma as prevalent in client consultations with UK advisers. We provide consultations free of charge with instant portfolio ‘look through’ analysis that, when attempted independently, can be timely and complicated to assess. These assessments are currently showing risks and inconsistencies in sustainable model portfolios that may have been masked by recent strong equity performance in certain sectors and regions. We believe that a case study outlined below from a recent UK client consultation is representative of the issues many advisers face.

The scarcity of sustainability

If our main concern is the inconsistency of risk profiles between traditional and sustainable model portfolios, we should begin by focusing on the root cause of this inconsistency. This, in our view, is that the asset management industry’s product offering is still catching up to adviser demand for sustainable investment solutions.

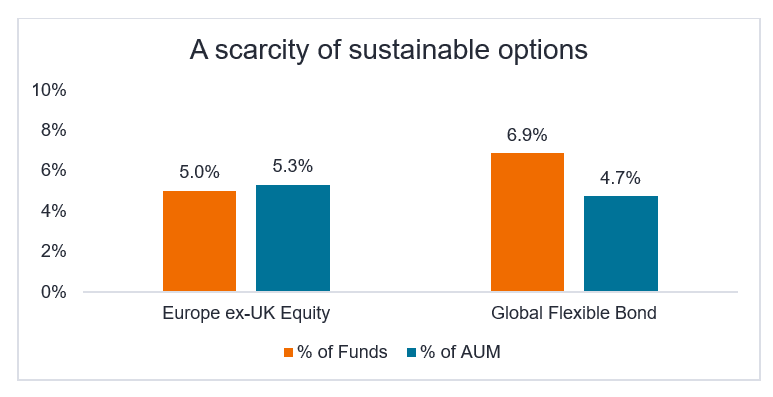

For example, an adviser investing in Europe ex-UK equity for their traditional model portfolio has a plethora of solutions available. That same adviser looking to mirror this selection in their sustainable model portfolios is limited to a much smaller selection. Compared to traditional Europe ex-UK equity, the sustainable options are severely limited with only 5.0% of the number of funds and 5.3% of the assets under management (AUM) as shown in Figure 1. There is a similar discrepancy within global fixed income.

Figure 1: Availability of sustainable funds and AUM

Source: Janus Henderson PCS Team, Morningstar. Percentage of all funds and AUM that explicitly indicate any kind of sustainability, impact or ESG strategy in their prospectus or offering documents, as at 1 June 2021.

Source: Janus Henderson PCS Team, Morningstar. Percentage of all funds and AUM that explicitly indicate any kind of sustainability, impact or ESG strategy in their prospectus or offering documents, as at 1 June 2021.

Granular or global?

This availability challenge for advisers makes it easy to understand why many sustainable model portfolios take a different approach to traditional model portfolios. If, for example, an adviser owns a Europe ex-UK equity fund in their traditional model portfolio and wants to select a sustainable European equity ex-UK fund but there are none available for the sustainable model, the likelihood is they will transition to a global sustainable fund. The result is often that the different approach presents a different set of, often unintended, risks.

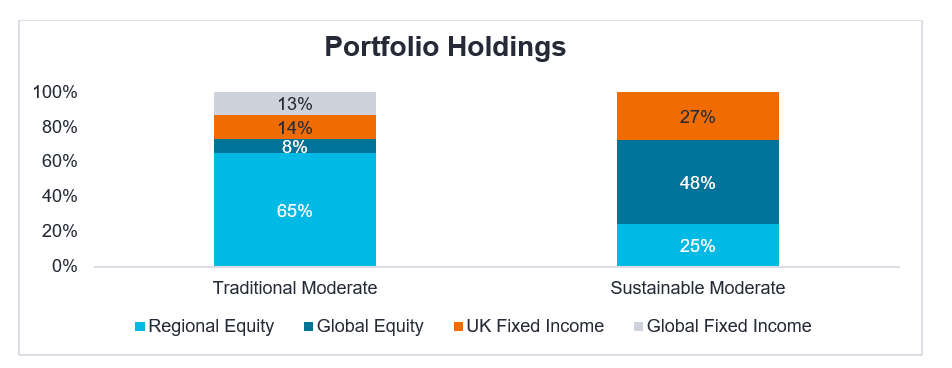

The example portfolios in Figure 2 show exactly this phenomenon in our recent UK client consultation case study. Within equities, the traditional model portfolio includes fewer global strategies, with more granular regional equity allocations, while the sustainable model portfolio relies more on global equity. Within fixed income, the phenomenon is the opposite with the traditional model portfolio fixed income allocation split between UK and global fixed income and the sustainable model with all its fixed income allocated to the UK. As we will discuss, we believe these asset allocation shifts – and therefore risk shifts – are attributable to the relative paucity of sustainable strategies in certain categories, which has forced the adviser in this case study to find alternative categories.

Figure 2: Portfolio holdings – significant differences

Source: Janus Henderson PCS Team, as at 1st June 2021. For illustrative purposes only.

Different risks mean different returns

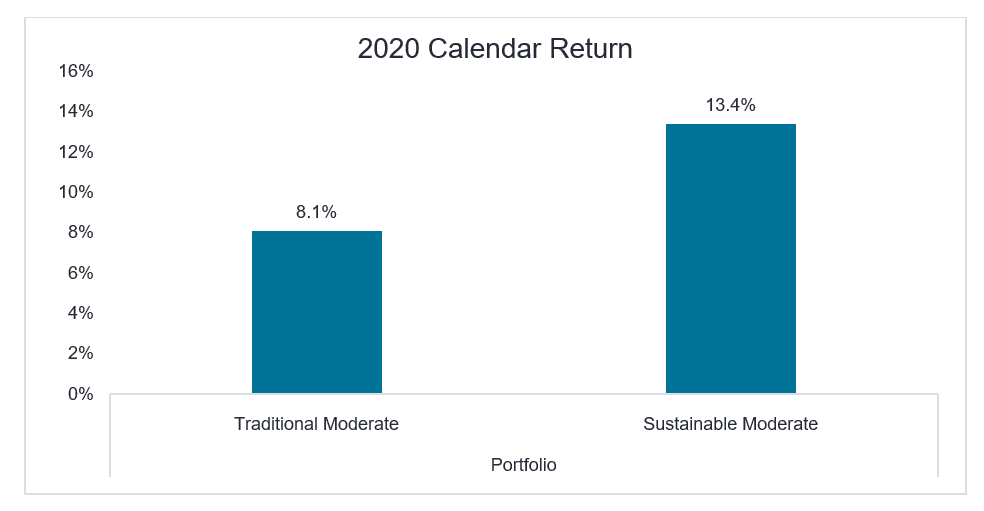

The inconsistent asset allocation creates a meaningful return divergence. The sustainable model portfolio has fared well in the last year with a calendar return of 13.4% in 2020, returning approximately five percentage points more than the broader ‘traditional’ portfolio (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Traditional vs Sustainable – 2020 returns

Source: Janus Henderson PCS Team, Morningstar. Cumulative 2020 Calendar returns, net of fees (GBP).

Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

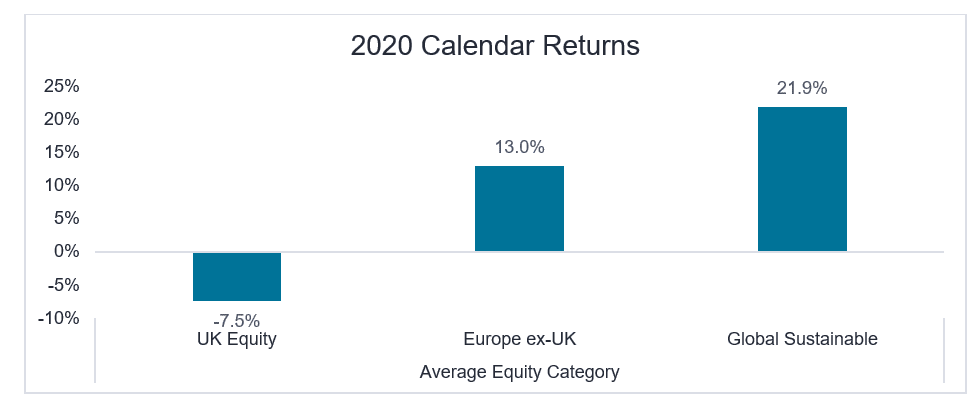

The scarcity of sustainable regional equity strategies is one of the many reasons for the sustainable model being underweight regional equity strategies and overweight global equity strategies. This introduces meaningful return differentials as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Regional vs Global equity – 2020 returns

Source: Janus Henderson PCS Team, Morningstar. Aggregated calendar returns in 2020 (GBP) of global sustainable equity, Europe ex-UK and UK equity Morningstar categories, net of fees, reported as of May 2021.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

Additional considerations

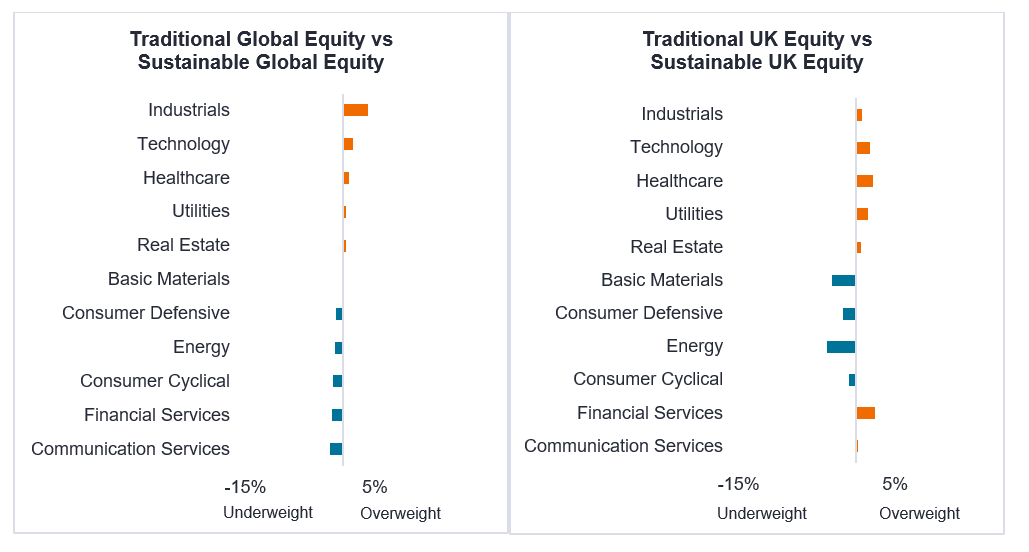

The differences between traditional and sustainable solutions are not just attributed to regions. It is interesting to note that, even when controlling for regional differences (e.g. global versus UK), a sustainable implementation alone can often introduce a style and sector tilt.

Comparing the sector exposures of global and UK funds versus their sustainable counterparts, we see global sustainable equity funds tend to have a stronger bias towards the technology and healthcare sectors (Figure 5). These sectors generally outperformed in recent years, especially in 2020 as ‘beneficiaries’ of the COVID-19 crisis. Our analysis shows that managers of sustainable funds have typically been less exposed to cyclical sectors, such as consumer cyclicals, energy and communication services, relative to broader equity funds.

Figure 5: Traditional vs Sustainable – sector exposures

Source: Janus Henderson PCS Team, Morningstar as at 1 June 2021. Sector exposures of funds’ holdings in the Morningstar categories, comparing global equity vs Sustainable Global equity and UK equity vs Sustainable UK Equity.

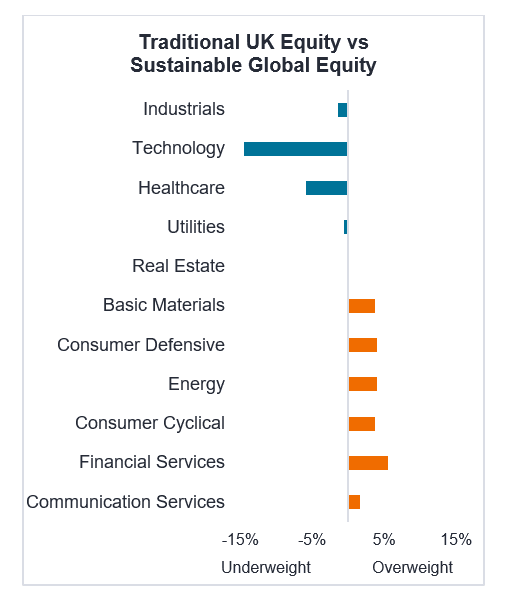

Taken to the extreme, a swap from traditional UK equity to a sustainable global equity would introduce a significant sector tilt (Figure 6):

Figure 6: A shift to a sustainable global equity model

Source: Janus Henderson PCS Team, Morningstar, as at 1 June 2021. Sector exposures of funds holdings in the Morningstar categories, comparing global ESG equity versus UK equity.

Looking forward

The unfortunate reality today is that selection is still limited for many portions of advisers’ sustainability asset allocation. The appropriate risk management tools and asset allocation perspective is indispensable for advisers focused on building sustainable model portfolios while limiting unintended asset allocation tilts, biases, drifts, and other risks. These, in our view, are important considerations in maintaining asset allocation risk consistency across model portfolios and finding a sustainable method to accomplish your clients’ sustainable investing goals. We would be delighted to contribute to conversations on the issue.

The client case study is used for illustrative purposes only.

This information is issued by Janus Henderson Investors (Australia) Institutional Funds Management Limited (AFSL 444266, ABN 16 165 119 531). The information herein shall not in any way constitute advice or an invitation to invest. It is solely for information purposes and subject to change without notice. This information does not purport to be a comprehensive statement or description of any markets or securities referred to within. Any references to individual securities do not constitute a securities recommendation. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

Whilst Janus Henderson Investors (Australia) Institutional Funds Management Limited believe that the information is correct at the date of this document, no warranty or representation is given to this effect and no responsibility can be accepted by Janus Henderson Investors (Australia) Institutional Funds Management Limited to any end users for any action taken on the basis of this information. All opinions and estimates in this information are subject to change without notice and are the views of the author at the time of publication. Janus Henderson Investors (Australia) Institutional Funds Management Limited is not under any obligation to update this information to the extent that it is or becomes out of date or incorrect.