Boom-bust economics is back! Be warned…

John Pattullo explains why he believes a recession seems unavoidable and that we are back to the boom-bust economics of the '80s.

13 minute read

Key takeaways:

- Major economies are currently experiencing ‘cold turkey’ from the harsh increases in interest rates in response to the over‑stimulus of the pandemic era. We are back to boom‑bust economics – akin to the 1980s.

- Rate hikes are late, and their pace is increasingly aggressive into an already slowing economy. Central banks have panicked, chasing current headline inflation, which has of course been exaggerated by the Ukraine war.

- Now, the narrative is changing from an inflation scare to a severe halt/growth scare in global activity. A recession seems unavoidable as the ‘growth tax’ of oil and interest rate rises destroys demand. We expect unemployment will rise as inflation fades but these are both lagging indicators.

- Growth has peaked and inflation is peaking. We believe sovereign bonds will become the place to be into this severe downturn. The economic cycle still exists but needs to be managed accordingly.

In many ways over the last couple of years we have had a ‘war time’ response to the COVID‑19 crisis, with very easy fiscal and monetary policy working in the same direction, and unfortunately, overstimulating global economies. We are now approaching the ‘cold turkey’ stage.

This is not much different from the political business cycles we encountered in the 1980s before central banks became independent. Now, we are experiencing very strange, scary and short‑lived economic cycles with large swings that we believe are yet to come.

Currently, major economies are approaching one of the most significant macroeconomic turning points in recent decades. In our view, economic growth and inflation have reached their peak (certainly in the US) and central banks are tightening financial conditions at a time when their economies are heading into a slowdown. We believe that markets are pivoting from a ‘headline inflation’ hysteria towards what we see as quite an acute ‘growth shock and economic downturn’.

The chronic sell‑off in the bond markets this year has been driven by the hawkish turn of central banks and in particular the US Federal Reserve (Fed). Having fallen badly behind the curve, a scramble began to combat high inflation. The situation was then further compounded by the war in Ukraine, which simply exacerbated existing tensions in the economies (stresses in the food and energy sectors to name a few).

In the case of the Fed, facing a shortened window of opportunity to tame inflation it began ‘front loading’ interest rate hikes, raising rates in March and then again aggressively in May. In June, overly concerned with the recent ‘eye catching’ University of Michigan inflation expectations survey, which surprised to the upside, the Fed broke with its earlier communication and raised interest rates by a substantial 75 basis points (bp). At his press conference on 15 June, Chair Powell said that the central bank is “strongly committed” to bringing down inflation using monetary tools, which equates to higher interest rates until “compelling evidence” emerges that inflation is coming down.

Other developed world central banks also turned dramatically hawkish, ditching post-pandemic stimulus and picking up the pace of interest rate hikes in a bid to control surging inflation. At their last policy meeting in June, the European Central Bank (ECB), signalled an end to asset purchases as well as a 25bp rate hike (both in July) while President Lagarde was clear that a larger hike was to be expected in September.

The rapid and aggressive sell‑off in the bond markets has been indiscriminate – total returns across government bonds, investment grade and high yield corporate bonds are deeply negative year‑to-date. Interesting to note that credit has not been the main culprit. Until about mid-April, the poor performance of corporate bonds was mainly a result of rising yields (falling prices) of the underlying government bonds (in other words, their duration exposure). The situation has since changed. Fears of an economic downturn as a result of excessive central bank tightening has resulted in credit risk becoming a bigger factor now, driving credit spreads wider on worries that default rates will inevitably rise.

Where are we today?

Back in autumn 2021, we mentioned that April 2022 was to be a key inflection point for growth momentum in the economies – that it would begin to collapse from a year‑on‑year perspective given the strength of economic data twelve months previously. The growth outlook is currently looking even worse than we expected as every region of the world is being downgraded. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), GDP-weighted global growth is expected to be down 3.2% year‑on‑year in 2022 – a level normally seen in a recession. In the US, gross domestic product (GDP) growth was negative in the first quarter and given that it is expected to be around or below zero for the second (data should be out by the end of July), the country is heading for a ‘technical’ recession.

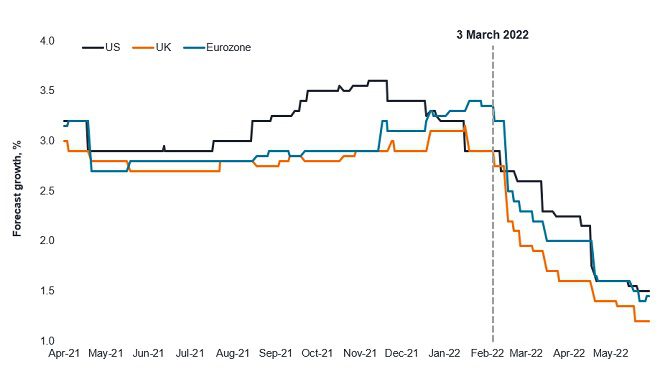

Figure 1 shows 2022 growth forecasts for the US, Europe and the UK. The additional downgrades since March are due to the war in Ukraine and the spread of Omicron/lockdowns in China, but the main culprit was the persistently higher gas and energy prices. Given hawkish central bank action as inflation keeps surprising to the upside, the debate on whether there will be a soft or hard landing (recession) in the economies has now intensified.

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, as at 24 June 2022.

Note: annual percentages, year-on-year.

Signals from the consumer

We lean on the bearish side of the consensus in this debate. In part due to the self-induced financial tightening as a result of rising interest rates and quantitative tightening (QT) plans, but also because of ‘consumer confidence’ data. This is one of the macro factors that we watch as we believe it has good predictive powers. Consumer confidence reports present timely data; they are released before the hard economic figures are out and not subject to revisions. A recent report by BofA Merrill Lynch concurs with our view – stating that consumers have a good sense of the outlook for income, future wages and unemployment.

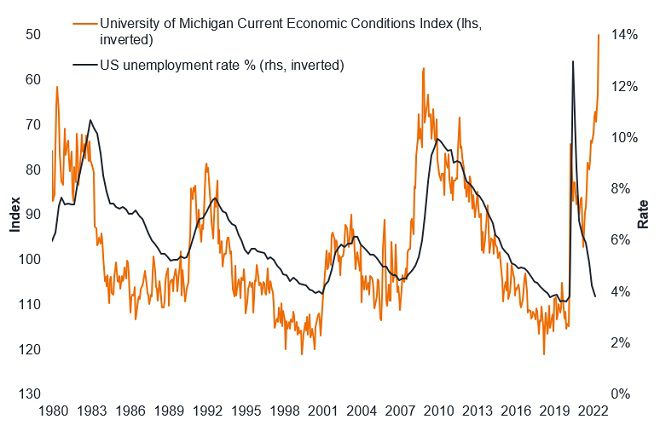

The latest consumer confidence figures show a drop across the globe to levels that are associated with recessions. Figure 2 shows the data for the US and reveals an interesting development – consumer confidence has decoupled from the employment market. Normally, when unemployment is low, consumers are very confident (and vice versa). But the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index has been declining steadily. It last fell by 8.4 points to 50.0 in June, well below earlier consensus expectations and its lowest recorded value since the series began in 1952. This paints a dismal picture of household sentiment as the impact of inflation and higher energy prices put a drag on confidence at the individual level.

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, as at 30 June 2022.

Note: US unemployment rate data is quarterly, as at 31 March 2022.

It seems that while the Fed is fixated on the hot labour market (low unemployment rate) believing that the US economy can flourish as they raise interest rates, US consumers are signalling the opposite and will probably cut spending, given that real income (income adjusted for inflation) matters and inflation is chipping away at their earnings. This pattern in the data is repeated across Europe and the UK.

More corroborating evidence for our bearish stance

Tightening financial conditions are being felt everywhere and there are increasing numbers of indicators that point to a significant slowdown in growth. Business confidence was steady until March when it started collapsing after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The latest eurozone quarterly bank survey showed that banks tightened credit in March. This could become a vicious circle as banks and businesses react together.

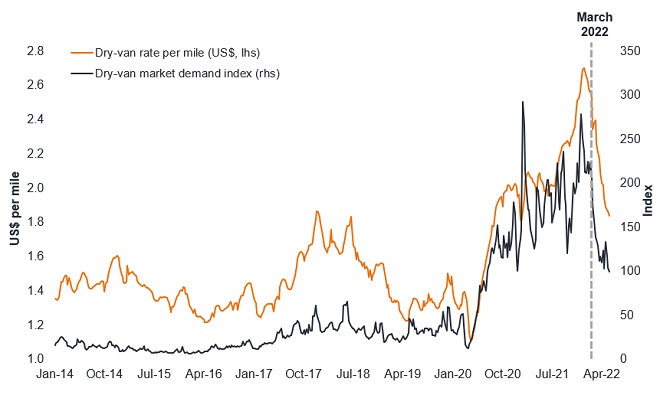

Trucking data in the US – another timely series, shows how some of the logistics problems in the past couple of years are starting to correct as the van rates are trending down (figure 3). An interesting feature in the chart is the demand index, and how it fell sharply in March. We have seen similar drops in a few other consumer areas such as sales of used cars and mattresses, indicating a real shift in consumer sentiment since then. Importantly, this is in the US, a relatively strong global economy.

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, weekly data, as at 10 June 2022.

Purchasing Managers’ Indices (PMIs) have also shown a downward trend. Global PMIs fell in April for both manufacturing and services, with the former decreasing to a 20-month low. More recently, in June, PMIs are showing a deceleration too. In the US, housing activity is on a downward trend and the negative impact of higher mortgage rates is just starting to show; housing starts dropped sharply in May significantly below expectations, while the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) housing market index has been falling for six straight months.

In the retail sector, recent profits warning from some of the biggest retailers in the US emphasise how many companies have over‑earned, over‑stocked and over‑hired on an unsustainable basis over the course of the pandemic – the inventory glut at major retailers in the US has recently worsened as retail sales fall. When companies buy too much during times of scarcity, the excess inventory later becomes a problem (and eventually a drag on growth) as stock has to be sold at a discount. Good examples of this are the recent large clearance sale by Target (general merchandise retailer) in the US and Samsung’s (electronics company) freezing of procurement orders. In another sign of how bad the inventory glut has become, many stores such as Gap, Walmart and Target are reported to be weighing the idea of refunding customers for returns but asking them not to send the unwanted items back given the costs involved!

Now, the odds of a recession increase with oil and energy prices on the rise. Rising energy prices are akin to a tax on growth. As well as leading to higher inflation, they also lead to a slowdown in the overall growth of the economy. If more of the household budget has to be devoted to energy, the same adjustment has to be made to non-energy spending, ultimately reducing consumption and demand for goods. Higher energy prices might also contribute to lower productivity and reduced investment. While energy is a more significant factor in the European economy than in the US, as Europe is particularly exposed to higher natural gas prices (a fallout of the war in Ukraine), US household spending on energy is also currently up to a level close to those seen during the two oil shocks of the 1970s.

Finally, the strength of the US dollar is another cause for concern. The currency has been supported by the classic safe‑haven flight by investors on a combination of sharply deteriorating global growth expectations, rising uncertainty and higher US rates.

Against this picture, with interest rates expected to rise substantially over the next couple of years and QT policies expected to be enacted in the developed world at a time when the economies are decelerating from a year‑on‑year perspective, the global economy is set to experience significant declines.

Where next for inflation?

From a year‑on‑year perspective given the high base data in 2021, inflation figures should generally come down from here. The real questions are by how much, and will they remain at uncomfortable levels?

Inflation trends in Europe and the UK will likely be shaped by energy prices, given their dependence on oil and gas. As for the US, we conducted a scenario analysis using Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’ assumptions on the impact of different oil prices on future levels of inflation. The results of our in‑house analysis showed that under a very hawkish scenario (of continuing shocks and rising goods prices), by February 2023 inflation could sit in an uncomfortably high range of 4.3-4.8% – regardless of oil prices. However, if the core goods cycle turns (as prices of core goods are coming down), then inflation can come down very quickly to below 2% in a couple of years’ time.

In addition, UBS economist Alan Detmeister, who accurately predicted the surge in US inflation in 2022 back in the autumn, now believes that core CPI has peaked but the high headline figure is likely to persist for a little while – energy prices have historically been persistent and stubborn to crack, until they do.

Where are we heading?

We believe that we are at a significant inflection point in the economies and that both growth and core inflation may have peaked – particularly in the US. The Fed is in an unenviable position. While it has begun raising interest rates to tame rampant inflation, the larger and faster rate hikes that it has signalled could severely dampen economic growth prospects and decimate demand. Given that it also has plans to unwind the stimulus measures of the pandemic era (through QT), the Fed is dangerously close to severely tightening financial conditions into an already slowing economy. Central banks in Europe and the UK are also on a mission to tame inflation, seemingly accepting the consequences of ‘demand destruction’ (slowing inflation will lead to reduced demand, which reduces economic growth).

Given the aggressive stance of central banks and the evidence of the macro factors detailed earlier, we believe that we are likely heading for a steep downturn. Soaring energy costs, a strong US dollar, a very flat yield curve and slowing growth in money supply are all the concoctions necessary for a recession. We feel that a hard landing is almost certain in the UK and Europe with a less severe downturn expected in the US.

Equity markets have already begun to price in recessions. Although equity prices are lower as price-earnings ratios have fallen, there has been limited revision to earnings forecasts and we expect several rounds of earnings revisions to materialise in the near future. Yet bond markets still seem preoccupied with the inflation narrative – decoupled from the growth story. We believe this will reverse soon.

As growth prospects take over as the dominant factor in bond pricing, we expect to see lower government bond yields (and higher prices). The prospects for corporate bonds (credit) are less clear and although fundamentals still look good in this part of the fixed income market, they will not remain immune in a severe downturn. In our view, high yield corporate bonds remain relatively expensive compared to investment grade counterparts. In addition, we see Europe as poorly placed compared to the US given the threat of an energy crisis this winter.

While we cannot know for certain where inflation would end, it is certain that our highly indebted economies post COVID-19 are not suited to higher interest rates or higher bond yields. We expect to see some sort of pivot from the Fed, potentially around the Jackson Hole conference in August, given that the Fed needs to see “compelling” evidence of inflation coming down. No doubt the market will be ahead of the Fed as usual.

Our conclusion is that a recession is unavoidable. Historian Adam Tooze, has been talking about a ‘polycrisis’ – a combination of seven or more stress/macro factors around the world, which include among them inflation, the war in Ukraine and higher food and energy prices. We have recently experienced an extraordinary boom‑bust cycle driven by COVID-19. Economic cycles will be more boom‑bust going forward in our opinion as the echo of COVID will linger – just as the echo of Lehman did after the Global Financial Crisis.

While the next cycles will be shorter and/or more violent, they are likely to also open up good opportunities for investors. We believe that bonds, which have been the problem for most of this year, could soon become the solution going forward, opening up opportunities for asset allocation in fixed income – particularly for increasing duration in portfolios.

Bearish: an investor who is pessimistic about the markets and expects prices to decline in the near- to medium-term.

Boom‑bust: a boom-bust cycle is a series of events in which a rapid increase in business activity in the economy is followed by a rapid decrease in business activity, and this process is repeated again and again.

Flat yield curve: a normal yield curve (a graph that plots the yields of similar quality bonds against their maturities) is upward sloping, where longer maturity bond yields are higher than short-term ones. In a flat yield curve the difference between long‑term and short‑term bond yields almost disappears. A flat yield curve is typically an indication that investors are worried about the macroeconomic outlook.

Front loading: in this article this refers to bigger interest rate increases in the early part of an interest rate hiking cycle by a central bank followed by smaller ones in the future.

Hawkish: an aggressive tone. For example, if the US Federal Reserve uses hawkish language to describe the threat of inflation, one could reasonably expect stronger actions from the central bank. Opposite of Dovish.

Quantitative tightening: a contractionary monetary policy that is the reverse of quantitative easing.

Spot rate: the price quoted for immediate settlement on an interest rate, commodity, security or currency. Transactions that settle immediately are said to occur in the spot market because they occur ‘on the spot’.

Recession/technical recession: a recession is a significant decline in activity across the economy lasting longer than a few months. A technical recession is when a country faces a back-to-back decline (two consecutive quarters of negative growth) in real GDP.

Soft/hard landing: a soft landing is a slowdown in economic growth that avoids a recession. A hard landing suggests a more marked economic slowdown, or a sharp downturn following a period of rapid growth.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- The Fund invests in high yield (non-investment grade) bonds and while these generally offer higher rates of interest than investment grade bonds, they are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- If a Fund has a high exposure to a particular country or geographical region it carries a higher level of risk than a Fund which is more broadly diversified.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.