Square root recovery

A decade on from the Global Financial Crisis, economic recovery has turned out to be both one of the weakest, and the longest, in modern history. John Pattullo shares his views on economic growth since the downturn, and into the future.

Remember 2009, when a year and a half after the worst financial crisis to hit the globe since the 1930s finally looked to be over, and economists had begun speculating over the likely shape of the recovery? The discussions turned emphatically alphabetical with various letters V, U, W and L thrown into the debate, and when they ran out of suitable letters, squiggly mathematical symbols (notably George Soros’ inverted square root sign) would do nicely.

Nearly eight years on, disappointingly, economic recovery has turned out to be both one of the weakest, and the longest, in modern history with many bumps along the way.

In the US, where economic recovery began earlier than the rest of the developed world, growth has been uneven, both geographically and through the years, and at levels only modest at best. Reaching its eighth year and 96th month on 30 June, this has been one of the longest economic cycles in the US, behind only two others — the 1960s (106 months) and the 1990s (120 months).

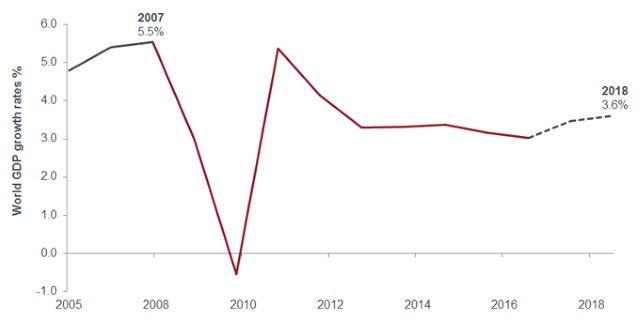

Nevertheless, there has been some positive news recently that the fairly tepid growth may have begun to accelerate. In October, the International Monetary Fund upgraded its forecasts for 2017 and 2018, stating that the world economy is gaining momentum, enjoying its most widespread growth since the temporary bounce back from the global recession in 2010.

However, many remain concerned that despite this benign short term outlook, the underlying growth dynamics in many advanced economies remain weak. This is based on low levels of investment, sluggish productivity and protectionist policies among other structural factors.

Today’s alphabet soup of economic recovery

Since the downturn, monetary policy efforts aimed at propelling economic growth have successfully brought about considerable asset price inflation, but very little wages or goods inflation. Did central bankers target the wrong sort of inflation?

The current economic expansion is a most unusual one. Different parts of the economy have displayed different shapes of recovery. Asset prices have had a V-shaped recovery, falling sharply but bouncing back even faster and continuing to rise. In fact equities seem to be reaching a new peak every day (widely referred to as “the most hated bull market ever”). The result has been more inequality in society with the rich getting richer and the poor, getting poorer; a situation exacerbated by new structural forces in the economy. One example is changes in the work force with a rapidly expanding new class of workers — the precariat — defined by the instability and insecurity of their jobs.

Productivity and real wages, which fell and failed to recover, exhibited a classic L shape. Economic growth (as in gross domestic product, GDP), however, has taken on a square root shape. As the chart shows, post the financial crisis the world economy collapsed, rebounded and has since almost plateaued.

A square root recovery

[caption id=”attachment_249762″ align=”alignnone” width=”640″] Source: OECD (2017), “OECD Economic Outlook No. 101 (Edition 2017/1)”, OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database). Dotted line represents forecasts for 2017 and 2018.[/caption]

Source: OECD (2017), “OECD Economic Outlook No. 101 (Edition 2017/1)”, OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database). Dotted line represents forecasts for 2017 and 2018.[/caption]

This has resulted in a dilemma for central banks. Numerous quantitative easing (QE) policies in the ten years since the financial crisis have failed to produce the desired inflation and growth environment. Lack of investment and productivity have contributed to the low growth pattern, while deteriorating demographics, deflationary effects of technology and behavioural changes in consumers have all contributed to the slow growth and low inflation world that we now live in. These factors are unlikely to disappear any time soon.

As a result, many tools used by central banks in gauging the economy and setting policy now look flawed, and with interest rates at such low levels, central bankers are facing the lobster pot problem, where they cannot get out of QE as easily as they assumed. The US Federal Reserve has announced a very gradual tapering of its balance sheet while emphasising that rate hikes will be slow, gradual and data dependent, while the European Central Bank has also indicated a gradual tapering of its asset purchases. The emphasis is very much on the ‘gradual’.

Going out with a big bang or a whimper?

Despite the recent optimism on higher economic growth rates, given the fundamental picture of both short and long-term structural factors that impede growth and inflation in today’s world, we believe, that we are likely to stay in the square root for a long time.

We also do not think that the economy will go out with a bang, but a whimper, and will continue to limp along for the foreseeable future. However, if there is another downturn, the underlying causes could be geopolitical, China-induced or from an asset price bubble, which could trigger a correction, but not, in our view, from an inflationary economic boom.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- The Fund invests in high yield (non-investment grade) bonds and while these generally offer higher rates of interest than investment grade bonds, they are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- If a Fund has a high exposure to a particular country or geographical region it carries a higher level of risk than a Fund which is more broadly diversified.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.