The Great Transition: demographic change in China

7 minute read

Jennifer James and Ales Koutny, emerging market specialists within the Global Bonds Team, interpret the data in China’s latest census, highlighting pressing economic and societal issues that will need to be addressed.

Key takeaways

- Declining birth rates, a shrinking workforce and an ageing population are set to put pressure on old age dependency ratios.

- The ongoing imbalance between the number of men and women threatens to further aggravate population issues.

- Greater urbanisation to raise productivity, shifts in family planning and changes to pension ages are just a few of the measures China is using to meet the challenges of demographic change.

China has finally published its once-a-decade census data, with the release of the 2020 Census. While China’s total population has grown, the underlying data reveals that monumental changes are occurring, which, if not properly addressed, could spell trouble in coming years. The environmental, social and governance implications (ESG) could be enormous.

Since the early 1960s, China’s population has sharply increased from an estimated 600 million people to over 1.4 billion people. The massive increase in both absolute and relative levels in a short period of time helped the country to become the leading manufacturer to the world. An abundance of cheap labour, coupled with the globalisation of supply chains, put the country in pole position to benefit from this shift and generated strong economic growth. This was made official by its inclusion in the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001.

China’s relationship with its own population growth has always been complicated. From Mao Zedong’s belief that “the more people, the stronger we are” to Deng Xiaoping’s support for the one-child policy in order to raise living standards, China’s attempts to deal with population shifts have been cumbersome.

As China continues to ascend on the world stage, it now has to grapple with the same demographic trends that other nations face – an ageing society, shrinking workforce, lower fertility rates and male/female imbalance. However, what sets China apart is the speed of such demographic shifts. A decade ago, according to the 2020 Census data, China had six million more births than deaths every year, yet recent census data intimates that China could face its first population decline as early as next year.

Fertility rates

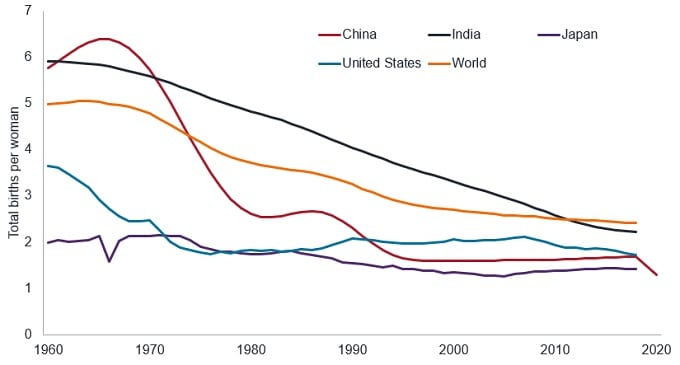

China’s fertility rates have quickly moved from a high of 6.4 children per woman in the mid-1960s to a low of 1.3 according to the 2020 census data. Moreover, this encompasses a significant deceleration due to the scrapping of the one-child policy in 2015. Estimates excluding the two years of anomalous fertility rates post policy changes put the current number at 1.1, only slightly ahead of South Korea’s fertility rate of 0.98, the world’s lowest. Although the massive reduction in birth rates puts China on a par with developed nations’ ageing societies, China has reached this level with astonishing speed. This will have significant consequences for the sustainability of the country’s finances in the long run, as a small younger cohort of the population will have to support a much larger ageing one.

Figure 1: declining fertility rate is a global phenomenon

Working age population

The 2020 Census data reveals that the total population in China has increased by 72 million (0.5% compound annualised growth rate) to 1.41 billion people between 2010 and 2020, although this is mainly due to improved longevity; ie, people living longer.

The working age population has actually decreased by 37 million (-0.3% CAGR) to 879 million people, as more people retire than younger people enter the workforce. China has one of the youngest retirement ages – 60 for most men, 50 for blue-collar female workers and 55 for white-collar female workers. Chinese authorities have already said that they would “gradually” delay the retirement age over the next five years, a deeply unpopular policy move.

Fortunately, even if the trends witnessed in the last decade continue to grow, China’s human capital should continue to increase in the next few years as the educational delta (the difference in educational attainment) between retirees and new graduates continues to support productive gains. Yet, before the end of the current decade, these improvements may not be enough to overcome such challenging demographics.

Internal migration and deindustrialisation

As the nation has become wealthier, one interesting theme that has arisen is the ‘rusting’ in certain parts of the country. China’s northeast provinces are going through a transition fairly similar to the shifts seen in the ‘American rustbelt’ that started in the 1980s.

In the ten years to 2020, the provinces of Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang in the northeast have seen a combined 10% population exodus in favour of wealthier more southern coastal areas. These northeastern provinces had previously benefited from a strong push to drive economic growth linked with ex-Soviet Union countries in the 1960s, but a continuous loss of incentives and competitiveness saw a number of industries closing their doors. This led to many workers in recent years searching for opportunities in more economically active areas in the south or closer to the coast.

China’s push for urbanisation has also created large-scale internal migration. The current urbanisation rate of 64% is nearly double the rate at the start of this century (36% in 2000), and arguably ahead of target to reach the current five-year plan aim of 65% by 2025. The rapid shift to a more city-based general population is in line with other countries’ experience of development. It is still below the developed countries’ average of approximately 80% urban rates, according to the UN World Urbanization Prospects 2018 Report, implying more to come. China’s appetite for raw materials to meet infrastructure and construction needs, therefore, is likely to remain robust.

Population gender divide

Due to a general cultural preference for male children and the government imposition of a one-child policy, there are approximately 35 million more men than women in China according to the 2020 Census data. To put this in perspective, it is only three million fewer than the entire population of Canada. Moreover, the declining ratio of women of childbearing age to men is expected to continue to worsen as the current skew towards males in the younger cohorts works its way through the age groups.

Therefore, even if the fertility rate remains the same, a downward pressure on the number of births should be expected due to the gender skew of the younger generation, as men cannot biologically have babies.

Avoiding the precipice

China’s census data has revealed that the country has made strong advancements in a number of areas, but it is facing a demographic cliff by the end of the decade. While income, life expectancy and urbanisation have all shown strong gains in the past decade, extremely fast societal ageing will place a burden on the country if not addressed soon enough. The country has tried a few initiatives to enable citizens to have more children, such as scrapping the one-child policy and creating a universal basic healthcare programme. Yet, as more people move into cities, rents and education costs will continue to rise. Most researchers expect China’s fertility rate decline to continue, potentially approaching the lows seen in South Korea.

Unless the country creates social and fiscal policies to strongly incentivise new births, an unseen and rapid societal transition will take place in the coming decades putting strains on the country’s finances and societal cohesion as a dwindling workforce cohort needs to offset the increasing costs of an ageing society.

Although there are no obvious immediate consequences, the potential long-term costs of inaction are enormous.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

Marketing Communication.