Breaking the link: GDP declines and default rates

Jenna Barnard and Nicholas Ware, Portfolio Managers in the Strategic Fixed Income Team, muse over how low corporate default rates may prove to be despite the pandemic-induced economic shock.

6 minute read

Key takeaways:

- Since late March, a confluence of factors has conspired to put credit markets in a sweet spot for returns; in this article we discuss the growing realisation of just how low default rates may prove to be relative to the size of the economic shock.

- Coming into the joint virus/oil shock, forecasters predicted default rates in the mid‑teens for the high yield market in line with previous peaks, applying their old models with no filter for the unique nature of this shock or the actions of authorities to minimise defaults.

- In many respects, this downturn has been very different to the experience of 2008‑09 when high yield markets ground to a halt for months on end. Both European and US high yield markets have benefited from the indirect impact of liquidity provision by central banks and, in particular, their focus on supporting the investment grade corporate bond market.

Since late March, when the systemic/liquidity phase of the Covid‑19 crisis concluded – courtesy of overwhelming central bank actions – the market environment has been a rather idyllic one for corporate bond investors. A confluence of factors has conspired to put the credit markets in a sweet spot for returns: historically cheap valuations; direct central bank purchases of corporate bonds, companies prioritising balance sheets over equity returns and guidance for zero or negative interest rates for many years to come.

A change of perception

However, perhaps the most important factor has been the growing realisation of just how low default rates may prove to be relative to the size of the economic shock. This is particularly the case in Europe where JP Morgan, the investment bank, recently forecasted high yield market default rates of 4% (this is actually below the historic average), reflecting extremely low distress in the market at current trading levels.

US high yield default rates are generally forecast to be around 10%, reflecting a high commodity weighting in that index, among other factors; but it is worth noting that this is still below the peaks of previous, less severe, economic shocks. Away from obvious problem areas, which should prove easy for active fund managers to avoid (traditional retailers, energy credits, Wirecard!), there are surprisingly few trouble spots at present. Authorities, both central banks and governments, have been intent on minimising defaults throughout this crisis and their efforts would appear to be meeting with some success.

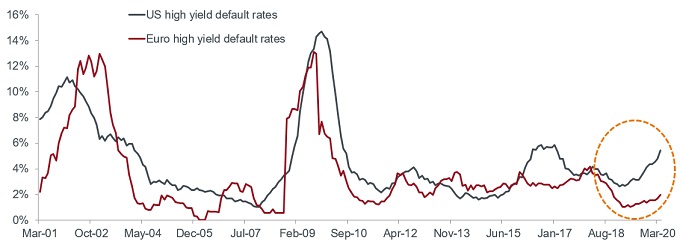

Naturally enough, we came into this joint virus/oil shock with forecasters predicting default rates in the mid‑teens for the high yield market, in line with previous peaks (see chart). This was a natural conclusion for top‑down modellers like Moody’s, who simply inputted historically high unemployment levels and low activity readings, with no filter for the unique nature of this shock or the actions of authorities to minimise defaults.

Chart: high yield default rates in Europe and US through past crises

Source: Moody’s, as at 30 April 2020.

Unconvinced by earlier ‘high’ projections

A Deutsche Bank study published on 23 March showed credit spreads were pricing default rates that were higher than anything seen historically. European high yield was implying a 5‑year cumulative default rate of 51.7%, assuming a 40% recovery, against a 5‑year historic worst of 32.5%. As a team, we were sceptical of these predictions and felt they were too high. Indeed, we added considerable additional high yield risk through March and early April, both in direct corporate bond investments and also using a European high yield credit derivative index (the iTraxx Crossover Index).

A number of factors explain the remarkably low current and forecast default rates in European high yield in particular. Before delving into them, it is worth pointing out a salient feature of this crisis, which is suppressing default levels in both geographies – namely, that the high yield markets in both Europe and the US have been shrinking for a number of years leading into the Covid‑19 shock. The European market peaked in size in June 2014 and the US in April 2015.

That is to say, this economic downturn, unlike the previous two (which were associated with high default rates) was not caused by excessive speculative lending in this area of the bond market. The tinder of bad lending, which could have sparked a huge default wave, was simply not there to the extent it has been in the past. In contrast, we worry about the loan market and the private credit market when thinking about the legacy of bad lending decisions in recent years.

Energy industry remains the bane of US high yield

Indeed, the singular area of bad lending for high yield bond investors in the last decade has been the US fracking/energy industry, which still comprises a significant part of the US high yield market courtesy of its debt binge a number of years ago and explains much of its consequent higher default rate at present.

Energy plays a much more important role in the US index (12.8%) as compared to Europe (5.0%) and also accounts for a large share of US defaults (ICE Bank of America, as at 25 June 2020). Year‑to‑date to the end of May, last 12‑months US defaults had climbed 222 basis points from the start of the year to a 10‑year high of 4.85% according to JP Morgan; notably energy accounts for 38% of that amount. They believe roughly half of the remaining defaults for 2020, to reach their (lower than consensus) 8% default forecast, will come from the energy sector.

Beneficial, indirect, impact of liquidity provision by central banks

The actions of European governments in providing direct aid to corporates has fed into lower default rates. We wrote two articles in April providing what we felt were interesting examples of some of the distressed European companies that were benefiting from government injections of liquidity. TUI (travel industry) secured a €1.8 billion loan from the German government through public lender KfW. A useful contrast is also provided by the fate of Europcar (car rental), which secured a €67 million loan for its Spanish subsidiary, backed by a 70% guarantee by the Spanish government and a €220 million loan backed by a 90% guarantee from the French government, while Hertz in the US has gone bust.

Both European and US high yield markets have benefited from the indirect impact of liquidity provision by central banks and their focus on supporting the investment grade corporate bond market, in particular. Investors have been willing to invest in new bonds issued by companies directly impacted by the travel and leisure industry shutdown (cruise lines, airlines, casinos, theme parks) in order to provide a war chest of liquidity to see these companies through even a second wave of the virus in the coming winter.

This is very different to the experience of 2008-09 when high yield markets ground to a halt for months on end, particularly in the immature European high yield market where there was virtually no new issuance for the best part of 18 months.

In many respects, this downturn has been unique. Our intent in this article was simply to highlight the distinct market characteristics going into this crisis and the supportive factors that have dampened the likely default losses for credit investors.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- The Fund invests in high yield (non-investment grade) bonds and while these generally offer higher rates of interest than investment grade bonds, they are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- If a Fund has a high exposure to a particular country or geographical region it carries a higher level of risk than a Fund which is more broadly diversified.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.