China’s trilemma and the renminbi’s fall

The renminbi's resilience has faltered as appetite for Chinese assets has turned. What does this mean for China's markets as the country faces a rekindled policy trilemma?

5 minute read

Key takeaways:

- China’s economic situation and a divergence in policy stance from the rest of the world has diminished appetite for Chinese assets and broken the renminbi’s resilience.

- Capital flight has ensued and reignited China’s trilemma in not being able to have open capital markets, independent monetary policy and a managed exchange rate all at the same time.

- While targeted fiscal action remains in China’s toolkit, volatility could persist in Chinese markets given that the renminbi acts as the main escape valve for the country’s economic pressures.

No longer a place to hide

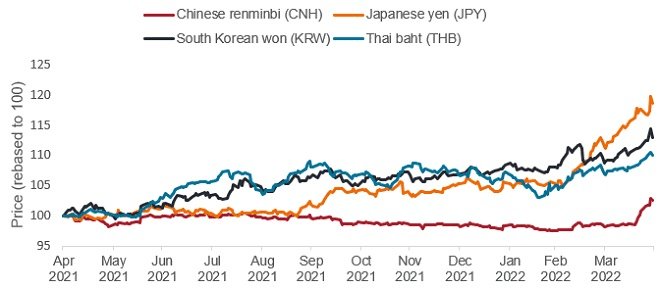

China’s onshore renminbi (CNH) has been an oasis of calm over the last year and up until recently, one of the few Asian currencies that had outperformed the US dollar. Its strength has been fortified by a strong twin surplus in China’s current and capital account, with a trade surplus driven by strong exports. The balance of payments – the difference between money flowing into and out of an economy – has shifted, with disruption to exports from lockdowns arising from China’s zero-tolerance approach to a resurgence in Covid cases. Coupled with policy uncertainty and diminishing growth prospects, these headwinds are dampening investor appetite for Chinese assets, depressing the currency.

Relative attractiveness wanes

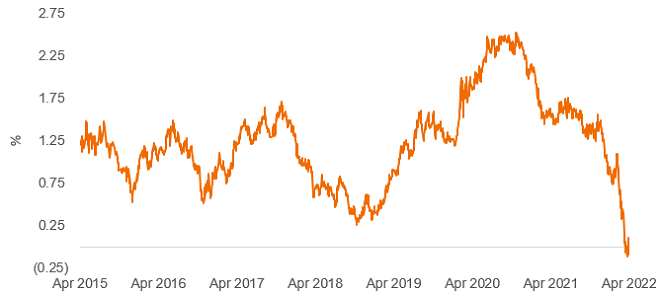

China has diverged from the rest of the globe in its tentative lean towards easing, while most economies are synchronised towards tightening. As China’s policy has diverged from the US, the yield differential between US and China 10-year government bonds has broken into negative territory for the first time since 2010. More broadly, as the average yield in other global government markets, such as the EU and UK, continues to trend higher, the incentive to invest in the Chinese market dwindles, particularly against a backdrop of policy uncertainty in the country.

The US Federal Reserve’s increasing hawkishness on a front-loaded tightening cycle has compounded the renminbi’s weakness and contributed to a reversal in the trend of money flowing into China. Capital inflows into the currency were encouraged by greater representation of China in fixed income and equities indices, but the tide has turned into US$44 billion of foreign capital outflows this year1.

China’s trilemma

China faces what is characterised in economics as a ‘policy trilemma’, where a country cannot simultaneously achieve exchange rate stability, independent monetary policy and free capital movement, but only two of these. China faces the requirement to ease financial conditions to reach its economic growth target. One of the ways it aims to do this is by reducing the FX reserve requirement ratio – the portion of reservable liabilities that commercial banks must hold onto, rather than lend out or invest, for foreign exchange activities – which has just been cut by 1% to 8%. This aims to increase liquidity in the domestic (onshore) US dollar market, which slows down renminbi depreciation. China will want to manage its renminbi dollar exchange rate to avoid swinging too much in either direction, as it wants its exports to be attractive, while not destroying demand for Chinese assets. Capital market reform towards openness has left it susceptible to outflows and so currency volatility is the unfortunate, but inescapable, side effect.

As renminbi weakness has been relatively contained, it appears that markets currently perceive only a temporary halt to the domestic re-investment of proceeds and repatriation of income. If we start to see a capital exodus akin to the 2014-16 period when the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) spent a trillion US dollars of its foreign reserves to stabilise markets, it would place further pressure on the currency as the main escape valve to stabilise the situation. This period marked a time of significant volatility in Chinese assets.

In light of the risk of further capital flight, we expect such currency moves to be only the beginning of a longer-term trend of depreciation. A continuation of this weakness, in our view, should be expected. A further 8-10% depreciation might be required for the renminbi to approach similar trends seen in other Asian currencies, as highlighted in Figure 1. The first real test for the currency is if the exchange rate versus the US dollar will be contained below 7 – psychologically the level deemed acceptable by market participants – or if it goes beyond this and the central bank directly intervenes in currency markets.

Uncertainty ahead

On the positive side, a weaker currency can help Chinese growth, as exports form a significant part of China’s economy; necessary if the country is to meet its 5.5% GDP growth target. As the government tries to tackle the challenges of stamping out Covid completely, progressing on its ‘shared prosperity’ agenda and maintaining growth around its expected target, volatility will likely remain high across Chinese financial assets. The ‘shared prosperity’ agenda has increased investor uncertainty around policy towards markets, as shown by the regulatory tightening over key strategic industries.

We believe the renminbi will act as the main escape valve for the country’s economic pressures and continue to depreciate. Chinese authorities until now have not shown particular attention to a specific level they will tolerate, but they have shown some signs of concern due to the speed of the move. To circumvent the trilemma, outside of monetary policy, targeted fiscal action offers a potential solution to reinvigorate growth. Financial assets are also dependent upon exceptional policies from government that can be enacted in very short order, such as coal tax cuts and extra infrastructure spending.

Volatility: The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index, moves up and down. If the price swings up and down with large movements, it has high volatility. If the price moves more slowly and to a lesser extent, it has lower volatility. It is used as a measure of the riskiness of an investment.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. It includes controlling interest rates and the supply of money. Monetary stimulus or easing refers to a central bank increasing the supply of money and lowering borrowing costs. Monetary tightening refers to central bank activity aimed at curbing inflation and slowing down growth in the economy by raising interest rates and reducing the supply of money.

Fiscal policy: Government policy relating to setting tax rates and spending levels. It is separate from monetary policy, which is typically set by a central bank.

Trade surplus: When a country’s exports exceed the value of its imports.

Yield: The level of income on a security, typically expressed as a percentage rate. For equities, a common measure is the dividend yield, which divides recent dividend payments for each share by the share price. For a bond, this is calculated as the coupon payment divided by the current bond price.

Hawkish: indication that central bankers are looking to restrict money supply to achieve their policy objective.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall. High yielding (non-investment grade) bonds are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- Emerging markets expose the Fund to higher volatility and greater risk of loss than developed markets; they are susceptible to adverse political and economic events, and may be less well regulated with less robust custody and settlement procedures.

- The Fund may invest in onshore bonds via Bond Connect. This may introduce additional risks including operational, regulatory, liquidity and settlement risks.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- If the Fund holds assets in currencies other than the base currency of the Fund, or you invest in a share/unit class of a different currency to the Fund (unless hedged, i.e. mitigated by taking an offsetting position in a related security), the value of your investment may be impacted by changes in exchange rates.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.

- The Fund invests in Asset-Backed Securities (ABS) and other forms of securitised investments, which may be subject to greater credit / default, liquidity, interest rate and prepayment and extension risks, compared to other investments such as government or corporate issued bonds and this may negatively impact the realised return on investment in the securities.