China’s economic rebalancing casts a cloud on property

Fixed income portfolio managers Jennifer James and Tom Ross consider how efforts to rebalance the economy in China are having far-reaching implications.

6 minute read

Key takeaways:

- Wealth disparities and a declining birth rate are encouraging China to engage in socio-economic engineering

- The policies pursued so far have been blunt and shocked markets, with the crackdown having particularly severe consequences for some of the heavily indebted property developers

- The timing is potentially inopportune given China’s economy was already showing signs of slowing, risking dragging down global economic growth.

Trying to describe China’s economy in recent decades has always been a lesson in economic gymnastics. From a more traditional communist command economy through to a capitalist hybrid model, China is now undergoing another reinvention as it seeks to share prosperity more equitably. It has even coined a name for it: “common prosperity”

Tackling wealth disparity

China’s economy has grown at a blistering pace in the last few decades, enabling it to climb up the rankings of per capita GDP and proudly assert earlier this year that it had eliminated extreme poverty within the country. The economic ascendancy has been unequal, however, with urban areas outpacing rural communities and a new billionaire class forming as the country both expanded its industry and embraced consumerism. Last year alone, the number of USD billionaires in China rose by 238 to 626 according to the 2021 Forbes List. The Gini coefficient – a measure of income inequality in a country – had been falling for several years prior to 2015 but more recently has been climbing. The latest figure for 2019 was 0.465 – a figure above 0.4 is indicative of a high level of income inequality (Source: CEIC, National Bureau of Statistics, September 2021).

For China, inequality comes with additional consequences. Its political system relies on stability so there is a desire to ensure the majority of people feel they have a stake in the system. China is intent on undergoing social engineering through policy tools. Few countries can do this effectively and even fewer have such firm ambition.

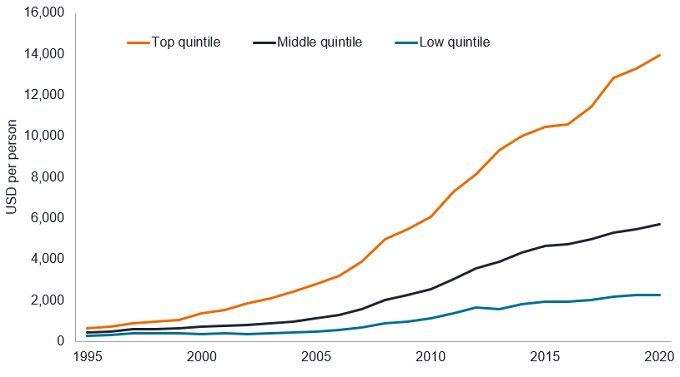

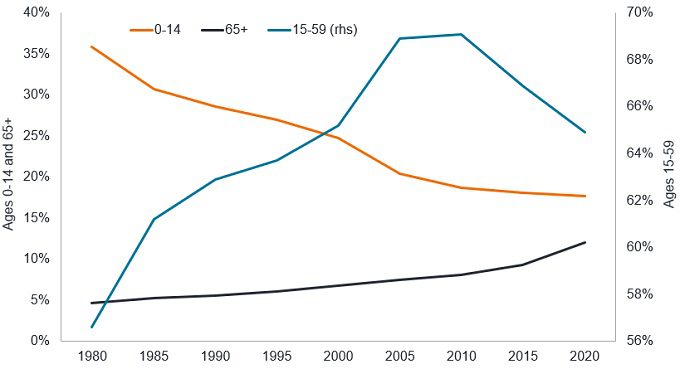

Figure 1a highlights the speed at which the wealthiest cohort have begun to move away from the middle and lower income cohorts. Common prosperity seeks to enlarge the middle class at the expense of the ultra-wealthy. The aim is social harmony. A second derivative of this would be to increase China’s birth rate (happier and economically stable people are more likely to have children). A major concern for authorities is the growing dependency ratio as the proportion of people aged 65 and over steadily increases while the population of working age shrinks as a share of the overall population (Figure 1b).

Figure 1a: Urban disposable income in China by quintile

Source: Morgan Stanley, CEIC, Wind, mean quintile urban disposable income, USD, 1995 to 2020. A quintile represents one fifth of the population.

Figure 1b: China’s population structure by age group

Source: United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects 2019, percentage of total population by broad age group, both sexes (per 100% of total population).

Blunt policy

The policy tools to achieve these social goals have so far targeted specific sectors that the government views as being either monopolistic (eg, technology) or those creating barriers for social upward mobility (eg, private educational tutoring, expensive healthcare and expensive property).

Methods have been blunt, often with little warning. As such, markets have not reacted well. To be fair, China has a habit of permitting rapid growth in industries, only to introduce tight regulation once an industry is firmly embedded. Examples include the imposition of safety standards on dairy products in the late noughties and a crackdown on luxury entertainment and gifts in recent years to tackle corruption. The regulatory reset currently taking place covers a much broader range of industries, from gaming to semiconductors, education to property.

House of cards

Currently, it is the property sector that is absorbing the most headlines, with the fallout from China Evergrande, the huge Chinese property developer, making waves. China has struggled to curb soaring property prices, not least because developers want higher prices to boost profits and local governments rely heavily on land sales for the bulk of their revenues, in some cases over 90%. In fact, land transfer revenues grew from CNY 50.7bn in 1998 to CNY 8.4 trillion in 2020, representing 8.3% of total GDP (China Banking News, 15 June 2021).

Pressure to cool prices has come from central government, which sees high property prices as an impediment to social progress and an expense that is discouraging households from having more children.

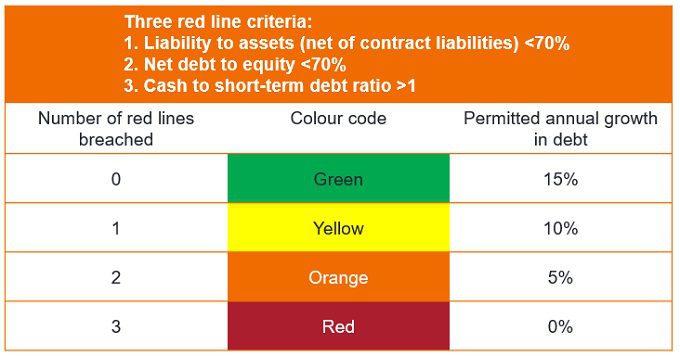

Recent efforts to cool prices began last year with the trial of the “three red lines” test. This concept demanded developers submit detailed reports of their finances to be assessed against three criteria. If one or more of these three lines is breached, then the regulator can limit the extent to which a developer can grow their debt.

Figure 2: Three red line criteria

Source: Bloomberg, press reports, September 2021

This policy is not expected to be formally implemented until June 2023, but the market has been quick to single out those companies most at risk of failing the three threshold criteria.

Evergrande is one of a number of property developers who are rapidly seeking to shore up their balance sheets. This is leading to a purge of inventories of housing and land stock, which is depressing margins. Evergrande’s issues are self-created as it could have been more proactive with its debt reduction by selling non-core assets, looking for strategic buyers and communicating better with investors. The challenge for Evergrande is its size. It is the biggest property developer in China and at the end of June 2021 had more than CNY 2.2 trillion (US$330 billion) in liabilities outstanding, which includes debt, deferred income tax and accrued trade payables (Source: Refinitiv Datastream).

Concerns that Evergrande may default on its debt has seen its bonds drop to around 25 cents in the dollar in mid-September 2021, essentially a quarter of their par value (Source: Bloomberg, 20 September 2021). The property sector relies partly on offshore funding to operate, which is why the response in the credit markets has been particularly severe.

Fears of contagion

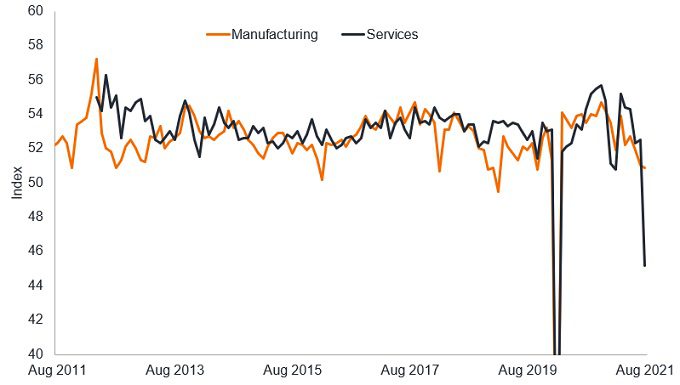

A messy restructuring would be bad for China and come at an inopportune time given that the country is already showing evidence of an economic slowdown (Figure 3).

Figure 3: China Purchasing Managers’ Indices reflect a weakening economy

Source: Refinitiv Datastream, National Bureau of Statistics of China, Purchasing Managers Index, Manufacturing Sector, Services, seasonally adjusted, August 2011 to August 2021. A reading below 50 indicates contraction.

Stalling confidence in China is leading to a tightening of liquidity conditions. The People’s Bank of China made several liquidity injections during September, including CNY120 billion (USD18.5 bn) on 22 September to help maintain liquidity in the financial system (Source: Xinhua, 22 September 2021).

For now, investors are having to gauge how much market pain the authorities in China are prepared to tolerate to achieve their goals. With China such a key player in the global economy, the risk is that fallout in its property sector spreads globally through markets.

When China coined the phrase “common prosperity” most investors assumed this meant the domestic economy; the law of unintended consequences could see it come to refer to China exporting its growth slowdown to all.

Socio-economic engineering: policies designed to deliver specific social and economic goals.

Command economy: an economy that is centrally planned by the state, the opposite of a

Capitalist economy where free enterprise and private ownership of capital drives the economy.

Dependency ratio: a demographic measure of the ratio of the number of dependents to the total working age population in a country

Monopolistic: a market dominated by one large supplier

Balance sheet: an accounting statement showing the assets, liabilities and capital of a business.

Par value: this is the price at which the bond was first issued and the amount the bond issuer agrees to repay at maturity.

Liquidity: the ease with which assets and financial instruments can be bought and sold; also describes flows of money around the financial system.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall. High yielding (non-investment grade) bonds are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- Emerging markets expose the Fund to higher volatility and greater risk of loss than developed markets; they are susceptible to adverse political and economic events, and may be less well regulated with less robust custody and settlement procedures.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- The Fund may incur a higher level of transaction costs as a result of investing in less actively traded or less developed markets compared to a fund that invests in more active/developed markets.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.

- In addition to income, this share class may distribute realised and unrealised capital gains and original capital invested. Fees, charges and expenses are also deducted from capital. Both factors may result in capital erosion and reduced potential for capital growth. Investors should also note that distributions of this nature may be treated (and taxable) as income depending on local tax legislation.