Front-end rates indicate riskier assets need a reality check

Global Head of Fixed Income, Jim Cielinski, explains his concern that riskier asset classes have yet to fully price in the likelihood of an economic slowdown as global interest rates march higher.

6 minute read

Key takeaways:

- With the Federal Reserve (Fed) focused on backward-looking employment data, shorter-dated interest rates have the potential to move even higher over the coming months.

- We believe that riskier segments of the bond market, along with equities, have yet to fully price in the risks posed by a higher cost of capital and economic slowdown that have weighed on markets this year.

- Investors should closely monitor sources of stress in both markets and the real economy that may be indicators of systemic weakness.

In this year of considerable financial market volatility, the front end of Treasuries yield curves have acted as both a driver of, and barometer for, future economic and market developments. Facing a nearly inevitable economic slowdown, bonds – including shorter-dated Treasuries – are not living up to their “safe-haven” status. The culprit, to the surprise of no one, is generationally high inflation. We knew that the eventual unwinding of accommodative, pandemic-era policy would be uneven, but inflation nearing double-digit annual rates in many developed markets has made the process perilous. Although we expect the worst of inflation to subside over the coming months, we believe interest rates will likely remain volatile until a clearer picture emerges on when consumer prices stabilize, the level at which they settle and – perhaps most importantly – what the one-two punch of inflation and a higher cost of capital mean for global economic growth.

The handoff commences

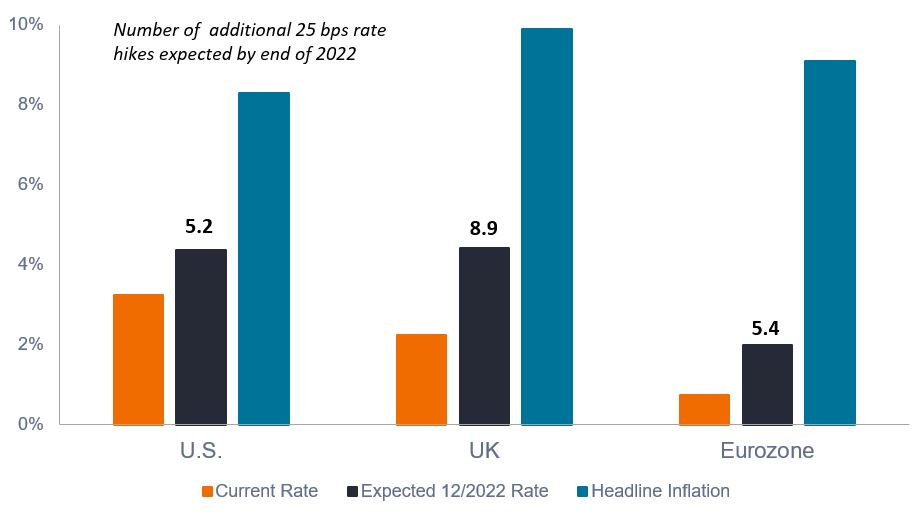

This year’s historic rise in front-end rates has been driven by central banks attempting to raise policy rates to the level necessary to combat inflation. They got off to a slow start. At the end of 2021, futures markets predicted that the federal funds rate would rise to 0.82% by this December. Already, the policy rate resides at 3.25% and futures markets see it climbing an additional 100 basis points (bps) by the end of the year. The 358 bps year-to-date rise in the 2-year U.S. Treasury yield indicates the market is taking the Federal Reserve (Fed) at its word that taming inflation priority number one.

Select policy rates and futures/swaps market expectations

Source: Bloomberg, as of 7 October 2022.

In this respect, the work of economists is nearly done. Forecasts for economic growth have been dialed back and futures markets even see the potential for U.S. rate cuts in late 2023 (not our view). We believe it’s now analysts’ turn to adjust their estimates to the reality of a slowing economy. This is true across the risk spectrum – for both equities and corporate credits. Over the course of this year, consensus forecasts for global economic growth have fallen from 4.4% to 2.9%, according to Bloomberg. The same metric for the U.S. has slipped from 4.1% to 1.6%. Meanwhile, 2022 earnings estimates for the MSCI World IndexSM and S&P 500® Index have slid 2.9% and 2.2%, respectively, from their mid-year peaks. We doubt that’s enough. Similarly, although the yield on investment-grade U.S. corporate credits appears to be an attractive 5.7%, most of that gain is due to higher interest rates. At 154 bps, the spread between these credits and those of their risk-free benchmarks is nowhere near what we’d expect them to be heading into an economic downturn.

Hike until something breaks

Rhetoric from Fed officials reinforce their newfound inflation-fighting chops. At 3.25%, the federal funds rate already exceeds the central bank’s expected long-term neutral rate of 2.50%. And it’s almost a given that this gap will grow over the coming months. Behind this push is the wage-price spiral that central bankers dread. Consequently, we doubt the Fed will pause rate increases until U.S. job gains roll over and wage growth begins to fall. If the Fed believes that a cooling labor market is the linchpin for taming inflation, although well below its year-to-date average, September’s still relatively healthy 263,000 change in nonfarm payrolls signals more hikes to come. Yet, given the long and variable lag of monetary policy, emphasis on this backward-looking indicator likely means a shallow recession – at the very least – is unavoidable.

Put another way, the Fed will hike until something breaks. The question is, what? Already the global bond market is stressed. Our view that markets could have handled a methodical normalization in rates never got tested due to inflation’s rapid emergence. Since then, markets have reacted – sometimes chaotically – to new macro realities, with the UK’s tax flop the most recent example.

Thus far, turmoil has been confined to financial markets. As indicated by history, that may not last, especially when the Fed seems laser focused on cooling the labor market. Unlike the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) when an acute source of risk existed in the form of U.S. housing, excessive debt – thanks to loose policy rates – is dispersed throughout the global economy. Dispersion, however, does not eliminate risks. Typically, it is the weakest segments of the economy that fail first. These developments are initially considered idiosyncratic until they start to pile up. By then, the market belatedly realizes it has something systemic on its hands. Another concern is market structure, especially given the amount of leverage in the system. A potent mix of leverage and pervasive use of derivatives only needs a catalyst to trigger in price dislocations or, in a worse-case scenario, market seizure.

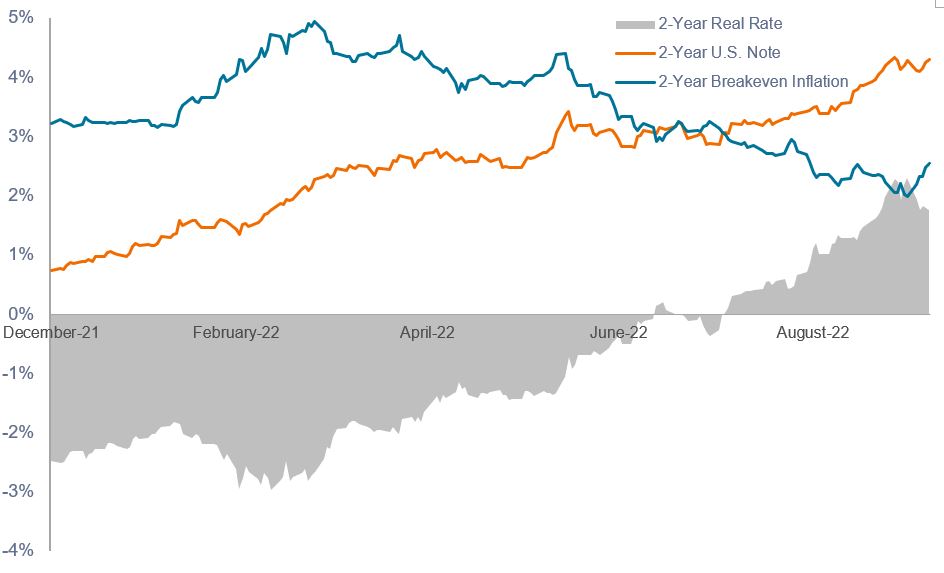

Manning the watchtower

Candidates abound as to what’s the next shoe to drop. Floating-rate debt, frontier markets and lower-quality corporate credits all bear monitoring. The cost of capital is increasing across the global economy. Keeping our focus on 2-year U.S. Treasuries, in the past year, its real yield (nominal rate less breakeven inflation) has climbed from below -3.0% to as high as 2.3%. Ten-year real yields have followed a similar, yet slightly less aggressive, path as the market prices in a slowing economy over a longer horizon.

2-year U.S. Treasury yields

Source: Bloomberg, as of 7 October 2022.

We believe investors’ focus over the coming months should be divided between inflation and whether riskier assets more fully incorporate a slowing economy, narrowing profit margins, and perhaps higher delinquencies into their prices. Two favorable developments are corporate managers having maintained balance sheet discipline, relative to other cycles, by locking in low-cost debt and U.S. mortgage lenders largely avoiding the poor decisions that preceded the GFC.

Still, the cost of capital has the potential to climb higher over the near term as labor market metrics like the 4-week average for initial jobless claims remain below cautionary levels. Lastly – and as evidenced by intermittent but ultimately short-lived rallies – the market needs a reality check on what the Fed and other central banks mean by taming inflation. U.S. headline inflation falling from 9.1% to perhaps 5.0% would not justify the “all clear” on riskier assets. This process is even more challenging in Europe. With UK headline inflation just below 10%, and not much lower in the eurozone, futures markets are anticipating these regions’ central banks to aggressively raise rates well into 2023 despite notable economic frailty. That is a recipe for stagflation, an environment in which we would expect both riskier assets and safer bonds to continue to suffer.

A yield curve plots the yields (interest rate) of bonds with equal credit quality but differing maturity dates. Typically bonds with longer maturities have higher yields.

Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point. 1 bp = 0.01%, 100 bps = 1%.

MSCI World Index℠ reflects the equity market performance of global developed markets.

S&P 500® Index reflects U.S. large-cap equity performance and represents broad U.S. equity market performance.

Stagflation is an economic cycle characterized by slow growth and a high unemployment rate accompanied by inflation.