Fixed income investors are confronting a thorny period as uncertain trajectories for both the global economy and monetary policy are fraught with risks regardless of which outcomes ultimately come to pass. Guiding investors on this journey will be the hopefully steady hand of the world’s central bankers as they seek to sustain momentum for the economic recovery without allowing inflation to get out of hand.

Whether these two forces are properly balanced has been on the minds of bond investors for much of 2021, starting with the early-year spike in Treasury yields as faith grew that large-scale vaccination efforts would help pull the global economy out of its pandemic-era slump. Although not as pronounced as what occurred at the beginning of 2021, the third quarter’s rise in yields indicated investors remain aware that the intermingled forces of economic reopening, inflation and an eventual reduction in accommodative monetary policy all have the potential to influence the near-term path for bonds. Unfortunately, the current sell-off has been driven by one of the less attractive combinations of these factors, with economic growth forecasts being dialled back at the same time persistent inflation is causing central banks to pull forward policy normalisation plans.

A not completely unexpected visitor

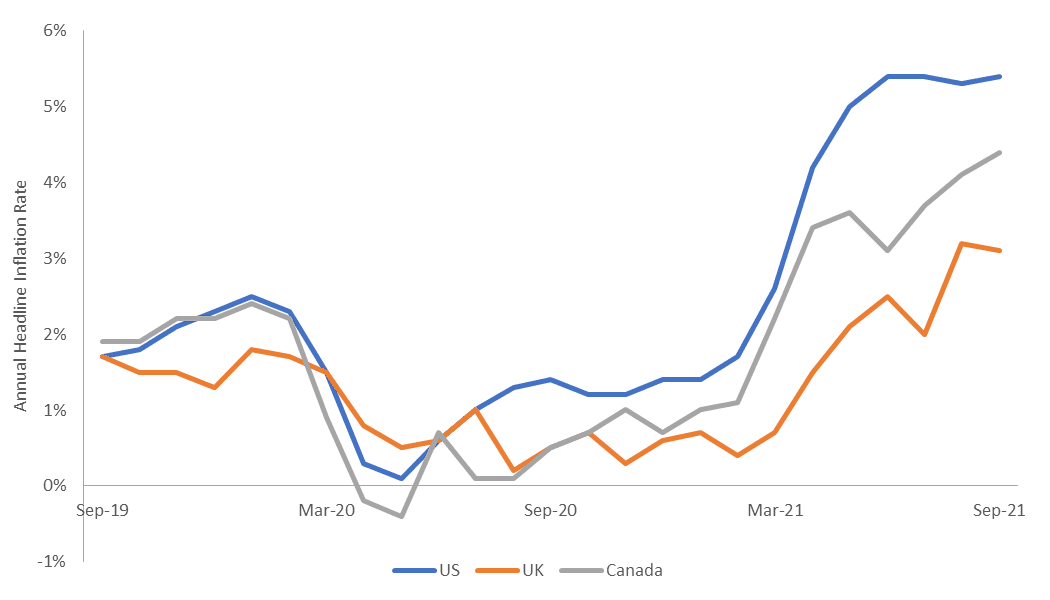

Given last year’s plunge in economic activity, an inflationary spike in 2021 on the back of unleashed pent-up demand was expected. Notably, the early-year rise in bond yields preceded any meaningful acceleration of inflation. That was not the case in the more recent sell-off as the annual change in the headline US Consumer Price Index had already breached 5% by May. What has caught policymakers off guard is the duration of accelerating prices as headline inflation has remained above that level ever since.

It’s no coincidence that lingering inflation is occurring at the same time as softening economic data. Rather than the “demand-driven” variety associated with a humming economy, much of the current inflationary pressure is attributable to the same supply-chain bottlenecks clouding economic prospects. While monetary policy tends to be less effective at confronting rising prices due to supply shocks, the current spike has put policy makers on notice as inflation has the potential to be self-fulfilling once consumers come to expect a sustained period of high prices.

Inflation in select countries

More worrying than the level of inflation has been the length of time it’s stayed above an acceptable range.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 29 October 2021

Taking the foot off the gas

After a year of rhetorical gymnastics by members of the Federal Reserve (Fed), the “taper” is here. The central bank’s balance sheet taper – a reduction of monthly asset purchases – is the first step in what will be the long journey of decreasing highly accommodative monetary policy. Case in point: once the Fed completes its taper – likely in mid-2022 – its balance sheet will still exceed US$8 trillion. In that context, this move can be seen as the Fed taking its foot off the gas rather than applying the brakes. The next step in policy normalisation should be the interest-rate “lift-off,” with the market pricing an initial 25 basis point hike by the middle of next year in the US. An uncomfortable jump in consumer prices is forcing other countries to be even more aggressive. New Zealand has already lifted rates by 25 basis points. And increasing hawkishness by the Bank of Canada – it has already terminated its bond-buying program – now has the market pricing in three rate increases by mid 2022, whereas the call was for only one just a few weeks ago.

And what of the front end?

An eventual increase in policy rates will inevitably put upward pressure on the front end of the yield curve. Given downgraded growth forecasts and the chance the Fed’s “transient” inflation call is proven correct, we don’t believe a higher US policy rate is imminent. Based on its track record, we suspect the Fed will err on the side of patience for fear of unduly curtailing growth during a global health crisis with an uncertain endgame.

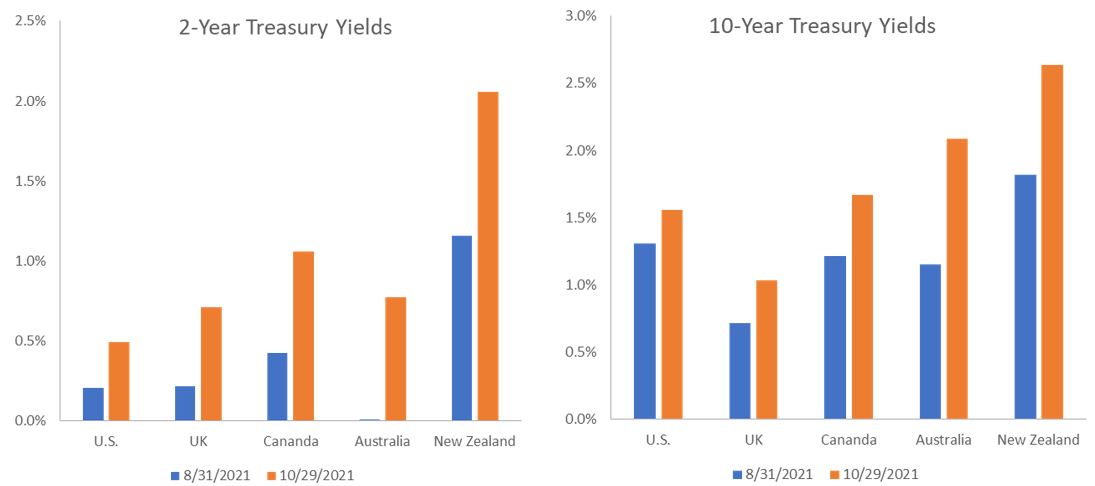

Markets, however, tend to move faster than monetary policy. The futures market is pricing in two hikes in the US by end of 2022 and in reaction, the 2-year Treasury yield has more than doubled, to 0.50%, since late August. These moves have occurred despite the Fed calling for just one rate increase in 2022. While we think the front end of the Treasuries curve has sold off a bit too aggressively, the trend is clear, and the bias is for shorter dated rates to rise.

The prospects for longer dated bonds are less certain. The pace of inflation is key. While stickier than anticipated, several contributors behind the recent uptick appear attributable to dislocations caused by the Delta variant. Among these are shortages of key goods and services, including drivers to carry products the “final mile” to customers. Should these issues be resolved and prices moderate, central banks will have more latitude to allow the economy to run. But if the Fed falls behind the curve – either in reacting to the current spike or to an acceleration of economic growth – longer dated yields could continue their climb. Conversely, a more aggressive hiking schedule, in any jurisdiction, may tap the brakes enough on growth expectations to place a ceiling on longer dated yields or see them reverse.

Two- and ten-year bond yields

Rates are on the move as inflation pushes up longer dated yields and – more recently – expectations for an acceleration of rate hikes by central banks send shorter dated yields higher.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 29 October 2021

An investor’s perspective

Rather than fretting over a half-empty glass, investors should keep in mind that rising rates are not necessarily a bad development. For over a decade, market participants have griped about astonishingly low bond yields. As we have stated in the past, it’s the pace of the rise that should dictate the trajectory of bond returns. If methodical, investors would have the opportunity to reinvest maturing securities at yields higher than what had been available only months prior. This tactic is all the more relevant for shorter-dated strategies that can exit highly liquid positions and reallocate towards longer-dated, higher-yielding securities of similar quality. If inflation proves more persistent than expected but policy rates remain on hold, shorter-dated strategies could be less affected by rising rates than those that have extended duration to chase returns.

We maintain the view that over the longer term, the disinflationary forces of demographics and technology get a vote on the trajectory of prices. But with inflation, expectations matter, and if consumers’ minds latch onto the fear of rising prices, global central banks may have to pull forward normalisation plans even more than what they’ve already announced. Given these cross-currents amid an ongoing pandemic and its economic ramifcations, vigilantly managing interest rate exposure should remain a high priority for fixed income investors.

Duration measures a bond price’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates and vice versa.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. It includes controlling interest rates and the supply of money.

Yield: The level of income on a security, typically expressed as a percentage rate. For equities, a common measure is the dividend yield, which divides recent dividend payments for each share by the share price. For a bond, this is calculated as the coupon payment divided by the current bond price.

Yield curve: A graph that plots the yields of similar quality bonds against their maturities. In a normal/upward sloping yield curve, longer maturity bond yields are higher than short-term bond yields.