For much of the past decade, Europe has carried an uncomfortable label: the region that promises a lot, regulates even more, and ultimately delivers too little growth. Investors got used to treating European equities as a value trap – cheap for a reason – while global capital gravitated toward a concentrated set of ‘champion’ stocks elsewhere, largely in the US.

And yet 2025 disrupted that narrative. Europe not only performed strongly; it did so while still looking inexpensive relative to global markets. That combination of better returns and lower expectations created a particular kind of setup for investors. It didn’t need perfection to do well, just to ensure that outcomes were less bad than feared, at a time when investors were seeking to diversify from the US. But can Europe continue to outperform?

Geopolitical pressures are forcing change

Europe has problems, but the question is whether or not the pressures bearing down on the region are finally strong enough to catalyse meaningful reform – and whether those reforms, even if slow, can unlock investable opportunities.

As we saw in 2025, Europe is undertaking a broad policy and geopolitical reset. The post-Cold War ‘peace dividend’, based on decades of relatively low defence spending and a comfortable reliance on the global security umbrella, has ended. That shift is structural, not cyclical, and it changes capital allocation priorities across the continent. At the same time, Europe’s longstanding homegrown constraints have become harder to ignore

The important investing implication is that many of Europe’s problems originate domestically, which means the levers to address them sit largely within Europe too. That does not guarantee success, but it does mean that the outcomes are less hostage to external factors.

Europe’s re‑rating potential is far from realised

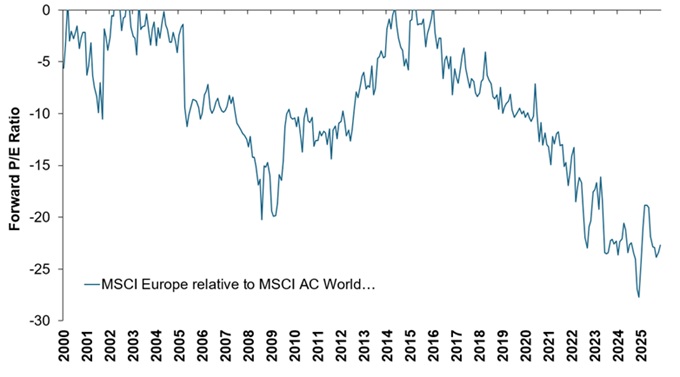

Europe’s improved equity performance in 2025 was not a result of Europe solving its structural issues. It happened while sentiment remained guarded and geopolitical uncertainty on the rise. And European equities remain priced at long-term lows relative to the MSCI World Index (Exhibit 1). That matters because pricing is ultimately about expectations.

Exhibit 1: Historic valuation discount creates entry opportunity

Source: Bloomberg consensus forecasts, Janus Henderson Investors Analysis, as at 28 November 2025.

Two particular features make Europe particularly interesting to us as investors:

- The “narrow door” effect (it if moves, it moves fast): Europe’s equity market is meaningfully smaller than the US. When flows turn positive, especially from outside the region, price moves can be abrupt. 2025 provided a live demonstration: when the door is narrow, you don’t need massive incremental demand to push prices materially higher.

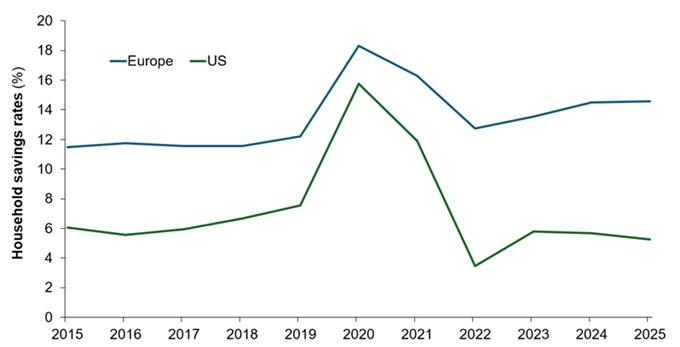

- A large pool of idle savings: Household savings across the EU are enormous (Exhibit 2), with a substantial share held in cash, earning little to no return. If proposals to mobilise this unused capital gain traction, resulting in a shift into stock markets, credit and productive investment (and the real economy), it would represent a powerful catalyst for growth.

Figure 2: Household savings are an untapped source of investment in the EU

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors Analysis, as at 7 July 2025.

Momentum is slow, but constructive

Progress on systemic reforms in the EU has been incremental and bureaucratic, and we expect that to continue. But former ECB President Mario Draghi’s proposed reforms are significant, with changes to securitisation, modernisation efforts tied to electrification and infrastructure, a changing stance on industry regulation – easing domestic burdens, while tightening policy for competitors – plus the potential to harness household savings. These developments will take time, but markets respond to credible direction of travel, particularly when expectations are starting from a low base.

We see prospects across a range of sectors in Europe:

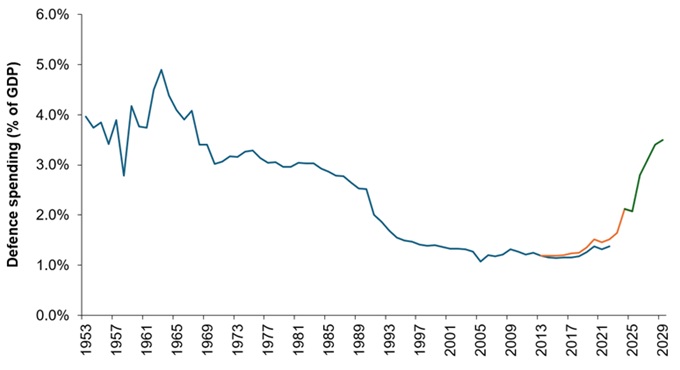

Defence – the catch-up story: The low level of defence spending over the past 30 years has been an historical anomaly in Europe, and it is important to recognise that the push for higher spending is a move back to a longer-term norm (Exhibit 3). Current capabilities fall far short of needed scale or capacity, with conflicts like Ukraine providing a particularly compelling illustration of how vital air defences (with anti-drone technology) are in modern warfare.

Exhibit 3: European defence spending is a return to the norm (% of GDP)

Source: Source: NATO, SIPRI, UBS as at 9 July 2025.

Note: The blue line refers to SIPRI data, the black line is NATO data (which goes back to 2014 only), the orange line is World Bank/UBS data. There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Drones have changed the cost calculation – it is unsustainable to use extremely expensive assets and missiles to neutralise cheap, low-technology weapons. Yet investors are not fully pricing in a sustained multi-year demand, rather valuing as if rearmament will be a short-lived cycle that fades quickly.

Aerospace – supply constraints: Civil aerospace faces a clear supply–demand imbalance. After COVID, air‑travel demand quickly returned to its historical growth path, but manufacturers and their complex, fragile supply chains struggled to rebuild capacity – the supply chain is complex, with thousands of components, and any single bottleneck a risk to output. Production at major airframe makers remains below pre‑pandemic levels, and planned increases will take years to normalise.

Importantly, the sector is in a “harvest period” following recent aircraft and engine launches, with no major reinvestment cycle due for 7–10 years. Strong demand, limited supply and a favourable capex window make aerospace an attractive opportunity.

Utilities – from the green revolution to an AI grid build-out: Europe is already on the path to transforming how it generates energy, replacing coal and nuclear with wind and solar, which has increased system volatility. A second wave is now accelerating as electricity demand surges, driven by AI and data centres seeking grid connections that already approach Europe’s current power demand. This collides with ageing grid infrastructure, much of it built decades ago. The challenge is no longer simple replacement but large‑scale expansion and reinforcement to handle greater loads and sharper fluctuations. Utilities and grid operators therefore sit at the centre of electrification policy, strategic resilience, rising AI‑driven demand, and regulated frameworks that support long-term investment.

This is far from exhaustive a list of investment opportunities in Europe at the moment. Other areas we view as promising include, for instance, basic materials in all its forms (mining & mining equipment, cement, steel), as well as semiconductors and their machinery vendors.

Can Europe sustain its performance?

Europe’s investment case reflects significant structural challenges but also a largely overlooked ability to address them. Because many issues are homegrown, the pace – not the possibility – of reform is what matters. Valuations and positioning remain low, creating room for positive surprises. At the same time, weak growth has itself become a catalyst, increasing political urgency to improve competitiveness, deepen capital markets and streamline regulation. Europe also holds vast household savings that could become a meaningful tailwind if mobilised into investment.

Reforms will not be linear, and Europe’s institutional complexity guarantees progress is likely to be gradual. But in a market that is sensitive to incremental flows, even partial progress – supported by enduring spending needs in defence, supply‑constrained aerospace markets, and accelerating grid investment – could support performance for longer than many expect. Europe doesn’t need a growth miracle – just steady progress in the right direction.

Capital: Refers to the financial value of an amount invested in a company or portfolio; in a fund context it reflects net asset value.

Discount: Refers to a situation when a security trades below its fundamental or intrinsic value.

MSCI World Index: is a widely followed equity benchmark that tracks the performance of large and mid-cap stocks across developed market economies, weighted for market capitalization (size).