Het verband wordt verbroken: bbp-dalingen en wanbetalingsgraden

Jenna Barnard en Nicholas Ware, portefeuillebeheerders in het Strategic Fixed Income Team, bespreken hoe lage bedrijfsstandaarden kunnen bewijzen ondanks de door pandemie geïnduceerde economische schok.

6 beknopt artikel

Kernpunten

- Since late March, a confluence of factors has conspired to put credit markets in a sweet spot for returns; in this article we discuss the growing realisation of just how low default rates may prove to be relative to the size of the economic shock.

- Coming into the joint virus/oil shock, forecasters predicted default rates in the mid‑teens for the high yield market in line with previous peaks, applying their old models with no filter for the unique nature of this shock or the actions of authorities to minimise defaults.

- In many respects, this downturn has been very different to the experience of 2008‑09 when high yield markets ground to a halt for months on end. Both European and US high yield markets have benefited from the indirect impact of liquidity provision by central banks and, in particular, their focus on supporting the investment grade corporate bond market.

Since late March, when the systemic/liquidity phase of the Covid‑19 crisis concluded – courtesy of overwhelming central bank actions – the market environment has been a rather idyllic one for corporate bond investors. A confluence of factors has conspired to put the credit markets in a sweet spot for returns: historically cheap valuations; direct central bank purchases of corporate bonds, companies prioritising balance sheets over equity returns and guidance for zero or negative interest rates for many years to come.

A change of perception

However, perhaps the most important factor has been the growing realisation of just how low default rates may prove to be relative to the size of the economic shock. This is particularly the case in Europe where JP Morgan, the investment bank, recently forecasted high yield market default rates of 4% (this is actually below the historic average), reflecting extremely low distress in the market at current trading levels.

US high yield default rates are generally forecast to be around 10%, reflecting a high commodity weighting in that index, among other factors; but it is worth noting that this is still below the peaks of previous, less severe, economic shocks. Away from obvious problem areas, which should prove easy for active fund managers to avoid (traditional retailers, energy credits, Wirecard!), there are surprisingly few trouble spots at present. Authorities, both central banks and governments, have been intent on minimising defaults throughout this crisis and their efforts would appear to be meeting with some success.

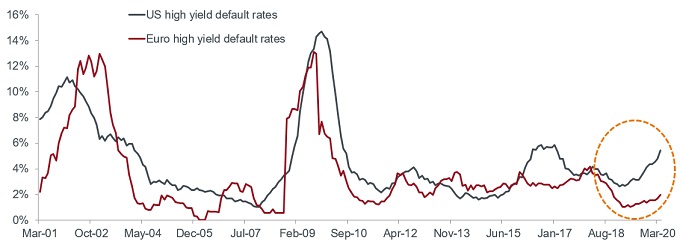

Naturally enough, we came into this joint virus/oil shock with forecasters predicting default rates in the mid‑teens for the high yield market, in line with previous peaks (see chart). This was a natural conclusion for top‑down modellers like Moody’s, who simply inputted historically high unemployment levels and low activity readings, with no filter for the unique nature of this shock or the actions of authorities to minimise defaults.

Chart: high yield default rates in Europe and US through past crises

Source: Moody’s, as at 30 April 2020.

Unconvinced by earlier ‘high’ projections

A Deutsche Bank study published on 23 March showed credit spreads were pricing default rates that were higher than anything seen historically. European high yield was implying a 5‑year cumulative default rate of 51.7%, assuming a 40% recovery, against a 5‑year historic worst of 32.5%. As a team, we were sceptical of these predictions and felt they were too high. Indeed, we added considerable additional high yield risk through March and early April, both in direct corporate bond investments and also using a European high yield credit derivative index (the iTraxx Crossover Index).

A number of factors explain the remarkably low current and forecast default rates in European high yield in particular. Before delving into them, it is worth pointing out a salient feature of this crisis, which is suppressing default levels in both geographies – namely, that the high yield markets in both Europe and the US have been shrinking for a number of years leading into the Covid‑19 shock. The European market peaked in size in June 2014 and the US in April 2015.

That is to say, this economic downturn, unlike the previous two (which were associated with high default rates) was not caused by excessive speculative lending in this area of the bond market. The tinder of bad lending, which could have sparked a huge default wave, was simply not there to the extent it has been in the past. In contrast, we worry about the loan market and the private credit market when thinking about the legacy of bad lending decisions in recent years.

Energy industry remains the bane of US high yield

Indeed, the singular area of bad lending for high yield bond investors in the last decade has been the US fracking/energy industry, which still comprises a significant part of the US high yield market courtesy of its debt binge a number of years ago and explains much of its consequent higher default rate at present.

Energy plays a much more important role in the US index (12.8%) as compared to Europe (5.0%) and also accounts for a large share of US defaults (ICE Bank of America, as at 25 June 2020). Year‑to‑date to the end of May, last 12‑months US defaults had climbed 222 basis points from the start of the year to a 10‑year high of 4.85% according to JP Morgan; notably energy accounts for 38% of that amount. They believe roughly half of the remaining defaults for 2020, to reach their (lower than consensus) 8% default forecast, will come from the energy sector.

Beneficial, indirect, impact of liquidity provision by central banks

The actions of European governments in providing direct aid to corporates has fed into lower default rates. We wrote two articles in April providing what we felt were interesting examples of some of the distressed European companies that were benefiting from government injections of liquidity. TUI (travel industry) secured a €1.8 billion loan from the German government through public lender KfW. A useful contrast is also provided by the fate of Europcar (car rental), which secured a €67 million loan for its Spanish subsidiary, backed by a 70% guarantee by the Spanish government and a €220 million loan backed by a 90% guarantee from the French government, while Hertz in the US has gone bust.

Both European and US high yield markets have benefited from the indirect impact of liquidity provision by central banks and their focus on supporting the investment grade corporate bond market, in particular. Investors have been willing to invest in new bonds issued by companies directly impacted by the travel and leisure industry shutdown (cruise lines, airlines, casinos, theme parks) in order to provide a war chest of liquidity to see these companies through even a second wave of the virus in the coming winter.

This is very different to the experience of 2008-09 when high yield markets ground to a halt for months on end, particularly in the immature European high yield market where there was virtually no new issuance for the best part of 18 months.

In many respects, this downturn has been unique. Our intent in this article was simply to highlight the distinct market characteristics going into this crisis and the supportive factors that have dampened the likely default losses for credit investors.

Dit zijn de standpunten van de auteur op het moment van publicatie en kunnen verschillen van de standpunten van andere personen/teams bij Janus Henderson Investors. Verwijzingen naar individuele effecten vormen geen aanbeveling om effecten, beleggingsstrategieën of marktsectoren te kopen, verkopen of aan te houden en mogen niet als winstgevend worden beschouwd. Janus Henderson Investors, zijn gelieerde adviseur of zijn medewerkers kunnen een positie hebben in de genoemde effecten.

Resultaten uit het verleden geven geen indicatie over toekomstige rendementen. Alle performancegegevens omvatten inkomsten- en kapitaalwinsten of verliezen maar geen doorlopende kosten en andere fondsuitgaven.

De informatie in dit artikel mag niet worden beschouwd als een beleggingsadvies.

Reclame.

Belangrijke informatie

Lees de volgende belangrijke informatie over fondsen die vermeld worden in dit artikel.

- Het is mogelijk dat een emittent van een obligatie (of geldmarktinstrument) niet langer bereid of in staat is om de rente te betalen of kapitaal aan het Fonds terug te betalen. Als dit gebeurt of als de markt denkt dat dit kan gebeuren, zal de waarde van de obligatie dalen.

- Wanneer de rentevoeten stijgen (of dalen), zullen de prijzen van verschillende effecten anders worden beïnvloed. In het bijzonder zal de waarde van obligaties gewoonlijk dalen als de rentevoeten stijgen. Over het algemeen wordt dit risico groter naarmate de looptijd van een obligatiebelegging toeneemt.

- Het Fonds belegt in hoogrentende obligaties (onder beleggingskwaliteit). Hoewel dergelijke obligaties doorgaans hogere rentevoeten bieden dan obligaties van beleggingskwaliteit, zijn ze speculatiever van aard en zijn ze gevoeliger voor ongunstige veranderingen in de marktomstandigheden.

- Sommige obligaties (op verzoek aflosbare obligaties) geven hun emittenten het recht om kapitaal vervroegd terug te betalen of om de looptijd te verlengen. Emittenten kunnen deze rechten uitoefenen wanneer dit voor hen gunstig is en dit kan invloed hebben op de waarde van het Fonds.

- Als een Fonds een hoge blootstelling heeft aan een bepaald land of een bepaalde geografische regio, loopt het een hoger risico dan een Fonds dat meer gediversifieerd is.

- Het Fonds kan gebruikmaken van derivaten om zijn beleggingsdoelstelling te verwezenlijken. Dit kan leiden tot hefboomwerking, wat de resultaten van een belegging kan uitvergroten en waardoor de winsten of verliezen van het Fonds groter kunnen zijn dan de kosten van het derivaat. Het gebruik van derivaten gaat ook gepaard met andere risico's, waaronder met name het risico dat een tegenpartij bij derivaten niet in staat is om haar contractuele verplichtingen na te komen.

- Wanneer het Fonds, of een afgedekte aandelenklasse/klasse van deelnemingsrechten, tracht de wisselkoersschommelingen van een valuta ten opzichte van de basisvaluta te beperken, kan de afdekkingsstrategie zelf een positieve of negatieve impact hebben op de waarde van het Fonds vanwege verschillen in de kortetermijnrentevoeten van de valuta's.

- Effecten in het Fonds kunnen moeilijk te waarderen of te verkopen zijn op het gewenste moment of tegen de gewenste prijs, vooral in extreme marktomstandigheden waarin de prijzen van activa kunnen dalen, wat het risico op beleggingsverliezen verhoogt.

- De volledige lopende kosten of een deel daarvan kunnen aan het kapitaal worden onttrokken, wat het kapitaal kan uithollen of het potentieel voor kapitaalgroei kan verminderen.

- CoCo's (Voorwaardelijk converteerbare obligaties) kunnen sterk in waarde dalen wanneer de financiële gezondheid van een emittent verzwakt en een vooraf bepaalde 'triggergebeurtenis' ertoe leidt dat de obligaties worden omgezet in aandelen van de emittent of gedeeltelijk of volledig worden afgeschreven.

- Het Fonds kan geld verliezen als een tegenpartij met wie het Fonds handelt niet bereid of in staat is om aan zijn verplichtingen te voldoen, of als gevolg van een fout in of vertraging van operationele processen of verzuim van een derde partij.