Market optimism ignited by geopolitical and economic development

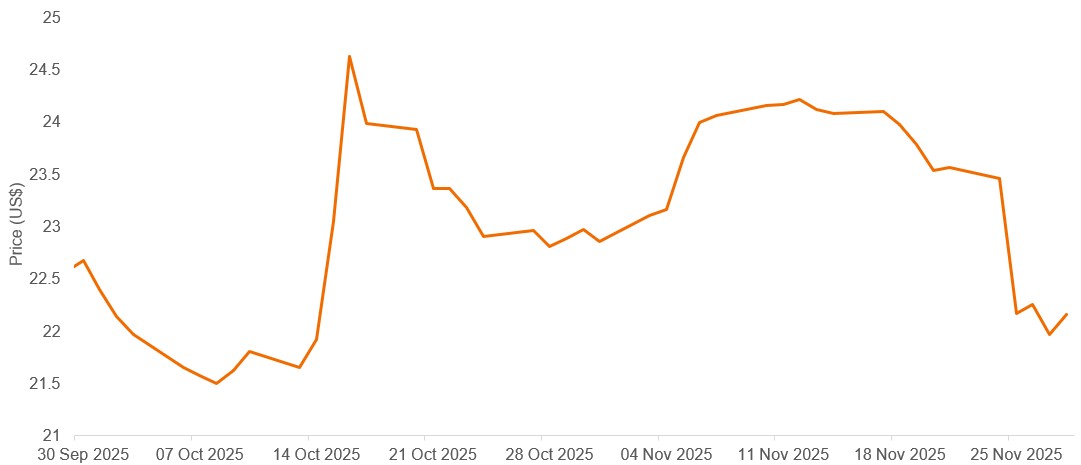

Lebanon has experienced a turbulent yet transformative period over the past year, marked by geopolitical and economic developments. Markets have responded with exuberant optimism, as reflected in Eurobond prices surging by roughly 12% in mid-October after Lebanon’s Economy Minister suggested that the Financial Gap Law[1] would soon be presented to parliament – even though a draft had not yet been submitted to or discussed by the cabinet.[2] This law is intended to address Lebanon’s large financial shortfall by defining how losses will be shared among the state, central bank, banks, and depositors – a critical step for restoring confidence and unlocking international support. The market reaction, however, appears premature given the complexity of the reforms and the political realities on the ground, namely resistance.

Lebanese dollar bond’s price surge on Financial Gap Law news

Lebanese dollar bond’s price development over the year to date

Source: Bloomberg, as at 28 November 2025. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

Two key drivers underpin market sentiment: the restructuring of Lebanon’s banking sector and the disarmament of Hezbollah. Both are seen as critical preconditions for unlocking international financial support and paving the way for an IMF programme. Yet, these processes remain fraught with challenges, and their timelines are uncertain. Here we delve deeper into the reforms and our insights from the recent IMF meetings in Washington.

Banking reform still faces hurdles

The banking sector overhaul began with the passage of the Bank Restructuring Law (BRL) in July. This law provides a framework for resolving Lebanon’s insolvent banks, but it is widely regarded as flawed. The IMF has called for 11 amendments to bring it closer to international standards. Two issues stand out:

- Appeals process: The BRL currently allows affected parties to challenge decisions extensively, risking indefinite delays. The IMF insists that only the legality of decisions should be contestable, not their merits.

- Hierarchy of claims[3]: The law permits deviations from the standard hierarchy of claims, under which shareholders’ equity is typically first in line to absorb losses. This raises concerns about arbitrary burden-sharing, particularly in Lebanon’s sectarian context, where patterns of bank ownership and depositor profiles differ sharply across communities.

The Financial Gap Law, expected to follow, is even more contentious. It will determine how Lebanon’s central bank’s estimated US$50–55 billion financial shortfall is distributed among the state, central bank, banks, and depositors. Key points of contention include:

- Whether gold reserves should be used to compensate depositors, easing social tensions, or reserved for public investment for long-term development.

- Treatment of the US$16.5 billion central bank loan to the government, which will affect the size of losses allocated to other stakeholders.

- Proposed write-offs of US$28 billion on banks’ balance sheets in terms of excess interest (approx. US$5 billion) and US dollar deposits converted from Lebanese pound deposits at an artificially high exchange rate (around US$23 billion), which would almost certainly trigger lawsuits from depositors, who argue that their deposits constitute fully legal claims on the banks.

- Application of the proposed $100,000 deposit protection limit – whether across all banks or on a bank-by-bank basis. The IMF favours the latter, more costly approach, arguing that the former is impractical to implement. However, the difference could amount to billions of dollars, making it a politically sensitive decision.

These issues underscore the complexity of implementing a fair and transparent resolution process. Even optimistic scenarios suggest that negotiations will be lengthy, making it unlikely that the law will be finalised before the May 2026 elections.

Disarmament of Hezbollah: A political and security challenge

Parallel to banking reform, Lebanon has started the process to disarm Hezbollah – under pressure from Israel, the US, the EU, and Gulf donors. The Lebanese army has proposed a phased plan, starting with clearing weapons south of the Litani River. However, significant obstacles remain:

- Hezbollah and its Shia support base view disarmament as an existential threat, fearing marginalisation and suppression similar to what befell the Shias and Alawites in post-war Syria.

- Public opinion polls show over 90% of Shia respondents oppose disarmament without reciprocal concessions from Israel.

- Despite recent military setbacks, Hezbollah retains substantial capabilities and external backing from Iran and Iraq.

The Lebanese army has said it lacks the capacity to enforce disarmament by the end of the year, raising the risk of civil conflict or renewed Israeli intervention. A negotiated solution appears the only viable path, but such an agreement would likely require broader Middle East diplomacy involving both Iran and Israel – an unlikely prospect in the near term.

Insights from the IMF Meetings in Washington

The October IMF meetings offered valuable perspectives on Lebanon’s reform trajectory. Discussions revealed a broad consensus: both Hezbollah’s disarmament and the passage of a credible Financial Gap Law are prerequisites for substantial international aid. These conditions are unlikely to be met before the elections, delaying any IMF programme.

Participants highlighted two key risks:

- Israeli invasion: Several speakers warned that Israel might resort to full-scale military action if disarmament stalls – a scenario one expert described as her “base case.”

- Political gridlock: Financial advisers of a bondholder group expressed scepticism about reform progress, accusing Lebanese politicians of playing a “double game” – publicly endorsing reforms while privately obstructing them. They expect no breakthroughs before parliamentary elections in May and plan to intensify lobbying efforts thereafter.

The IMF’s stance remains firm: banking sector restructuring must comply with international standards, alongside public debt restructuring and state-owned enterprise reforms. While essential for credibility, this uncompromising stance adds to near-term uncertainty.

Outlook for reform and why market optimism may be premature

The market’s optimism appears misplaced. The surge in Eurobond prices following the Economy Minister’s comments reflected expectations of imminent reform – expectations unsupported by the realities of Lebanon’s political and institutional landscape. Without amendments to the BRL and consensus on the Financial Gap Law, meaningful progress is unlikely before the May elections.

Similarly, the risks surrounding Hezbollah’s disarmament are underappreciated. The potential for renewed conflict – repeatedly emphasised during the IMF meetings – is not reflected in current market pricing.

In summary, Lebanon’s path to reform and development remains challenging. While recent steps – such as the formation of a technocratic cabinet and the appointment of a new central bank governor – signal intent, structural and geopolitical hurdles persist. In our view, investors should temper expectations and adopt a cautious wait-and-see stance. The coming months will be critical, but breakthroughs are improbable before May.

Footnotes

[1] The Financial Gap Law is a proposed Lebanese law designed to address the country’s banking crisis by allocating financial losses between the state, the central bank, commercial banks, and depositors.

[2] Since then, Lebanese bond prices have come off the peak by roughly 10%, at the time of writing on 28 November 2025.

[3] The hierarchy of claims refers to the legally established order in which different stakeholders are paid during a bank resolution or liquidation process. It ensures fairness and predictability when distributing remaining assets.

Emerging market investments have historically been subject to significant gains and/or losses. As such, returns may be subject to volatility.

Sovereign debt securities are subject to the additional risk that, under some political, diplomatic, social or economic circumstances, some developing countries that issue lower quality debt securities may be unable or unwilling to make principal or interest payments as they come due.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

Foreign securities are subject to additional risks including currency fluctuations, political and economic uncertainty, increased volatility, lower liquidity and differing financial and information reporting standards, all of which are magnified in emerging markets.

Volatility measures risk using the dispersion of returns for a given investment.

Eurobond: An international bond issued in Europe or elsewhere outside the country in whose currency its value is stated (usually the US or Japan).

Exchange rate: An exchange rate is the value of one country’s currency in relation to another, determining how much of one currency is needed to buy a unit of another.

Debt restructuring: The process of altering the terms of a company’s or country’s debt to avoid default and make repayment more manageable.

Interest rate: The amount charged for borrowing money, shown as a percentage of the amount owed. Base interest rates (the Bank Rate) are generally set by central banks, such as the Federal Reserve in the US or Bank of England in the UK, and influence the interest rates that lenders charge to access their own lending or saving.

State-owned enterprise: A large organization created by a country’s government to carry out commercial activities.

Shareholders’ equity: Shareholders’ equity refers to the owners’ claim on the assets of a company after debts have been settled. It is also known as share capital.

Technocratic: A government where ministers are appointed based on their expertise in a specific field rather than their political affiliations or electoral success.

Write-off: The removal of an asset’s or debt’s value from a company’s books, either partially or completely.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall. High yielding (non-investment grade) bonds are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- Emerging markets expose the Fund to higher volatility and greater risk of loss than developed markets; they are susceptible to adverse political and economic events, and may be less well regulated with less robust custody and settlement procedures.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- The Fund may incur a higher level of transaction costs as a result of investing in less actively traded or less developed markets compared to a fund that invests in more active/developed markets.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.