The start of 2026 has been defined by persistent uncertainty and rapid swings in risk appetite across global markets. Investors have had to navigate sharp reversals in leadership, periodic bouts of risk aversion, and a level of volatility that reflects genuine disagreement about the economic outlook. Inflation has eased, although it remains uneven across regions, interest‑rate expectations continue to shift, and geopolitical tensions – from great‑power rivalry to supply‑chain disruptions (see tariff threats) have sent ripples through asset prices.

Yet these forces have produced unusually wide dispersion in share‑price performance, with individual company fundamentals playing a greater role than broad market direction. And while volatility often reflects uncertainty, for investors with a value‑anchored, fundamentals-first mindset, this is the kind of backdrop that rewards disciplined stock selection.

Under‑owned, under‑researched, and inefficiently priced

At a structural asset class level, global smaller companies remain under‑owned and with limited coverage. Within the investable universe, there are thousands of names with minimal or no dedicated analysis. That scarcity of external research creates fertile ground for information and analytical advantage, where investors can identify overlooked quality and misunderstood risk.

This is also why passive exposure is a blunt and inefficient tool in this area of the market. Holding a broad basket of stocks without discipline and discernment can dilute the performance of good companies, by inadvertently loading up on those with weaker balance sheets or deteriorating business models. Active stock selection, grounded in a bottom‑up, information-driven process, is the practical way to exploit real mispricing that persists simply because nobody else is looking.

Why earnings can compound faster in small caps

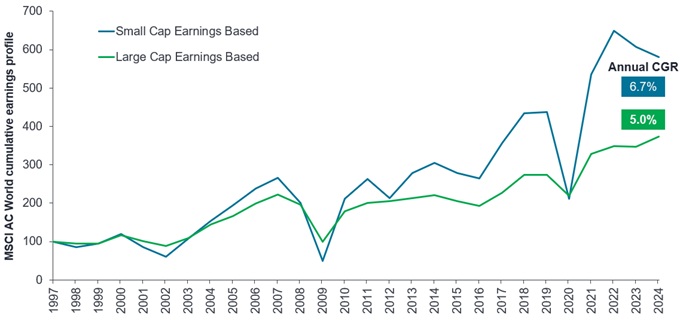

Since the late 1990s, global smaller caps have typically delivered higher annualised earnings growth than large caps over the longer term, with that advantage most visible in the period following market troughs (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Small caps earnings have outperformed large caps globally

Source: Refinitiv Datastream, Price indices rebased to 100, Janus Henderson Investors Analysis, at 31 December 2024. EPS Growth, FactSet, as at 8 January 2026. Past performance does not predict future returns.

Note: Indices used: Chart 1: MSCI World Small Cap and MSCI World Large Cap. Table 1: MSCI World Small Cap and MSCI World.

The intuition is simple. It is inherently easier for a capable smaller business to scale from, say, US$100m to US$1bn in annual revenues than it is for mega‑cap companies with a market capitalisation of (for example) $100bn to add the same proportionate growth to its already vast market base.

There are multiple paths to performance, including:

- Higher valuations: Starting valuations for small caps are depressed versus history and versus large caps, leaving room for re‑rating as fundamentals inflect.

- Earnings growth: Smaller firms can expand margins and reinvest at higher incremental returns, compounding faster when capital allocation is disciplined.

- Income: Dividends may be modest, but the impact is additive; even 40–50 bps (0.4% to 0.5%) more yield can compound meaningfully over a multi‑year horizon.

Crucially, we pay close attention to the incremental return on invested capital (ROIC), given the higher growth potential for businesses that reinvest a high proportion of their free cash flow. The combination of improving returns and ample reinvestment opportunity drives the bulk of long‑term value creation, independent of whether or not the market is paying attention in the short term.

Deglobalisation: a structural tailwind for local champions

For three decades, globalisation has rewarded scale, centralised supply chains, and globally dominant brands – classic territory for large‑cap stocks. Now, however, we are seeing companies and countries prioritising resilience over optimisation: shorter supply chains, more domestic sourcing, and tariff‑aware risks.

This shift is inherently supportive of smaller, local leaders in industrials, materials, business services and niche consumer categories – areas that are over‑represented in the small cap universe. As companies diversify their suppliers and governments look at how to incentivise on‑ or near‑shoring, smaller companies are well positioned to meet those needs – often faster, with greater customisation, and with less entrenched competition.

The same logic applies to the adoption of new technology. Smaller organisations tend to have flatter structures and fewer gatekeepers, enabling quicker deployment of productivity‑enhancing tools, including AI‑enabled software. With labour costs often taking up a larger share of earnings for smaller firms, even modest efficiency gains have the potential to disproportionately improve profit margins, relative to their larger peers.

The M&A factor

Finally, it is worth remembering that small‑ and mid‑cap companies consistently account for the majority of global merger and acquisition (M&A) activity, making this an important and recurring return driver for investors in the asset class. Takeover premiums typically average around 30%, demonstrating that corporate acquirers frequently value these businesses more highly than public markets do.

Strategic buyers and private‑equity firms often look down the market cap scale for bolt-on purchases to generate growth, or to buy-in existing specialised capabilities or innovative technology – particularly at times when market valuations are depressed.

In the current environment, where small caps trade at unusually wide discounts to large caps, the appeal to acquirers is even stronger. Strategic buyers can secure growth at far lower multiples than in large‑cap markets, and private‑equity firms can deploy cash to acquire companies with strong cash‑flow profiles and scalable business models.

This persistent demand provides a natural support for valuations and reinforces the opportunity available when public sentiment temporarily overlooks the small‑cap universe.

Smaller, stronger, sooner

The path to attractive returns does not hinge on perfect timing or a roaring multiple re‑rate. It rests on owning businesses that compound: strong incremental economics, prudent balance sheets, and management teams that allocate capital with discipline. From this starting point, investors can benefit from operational compounding, potential re‑rating, and cash returns – with the potential for M&A as a structural bonus. For long‑term, value‑minded investors willing to do the work, the combination of cheap entry prices, superior growth potential, and structural tailwinds makes this a compelling moment to lean in.

Active investing: An investment management approach where a fund manager actively aims to outperform or beat a specific index or benchmark through research, analysis, and the investment choices they make. The opposite of passive investing.

Balance sheet: A financial statement that summarises a company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity at a particular point in time. Each segment gives investors an idea as to what the company owns and owes, as well as the amount invested by shareholders. It is called a balance sheet because of the accounting equation: assets = liabilities + shareholders’ equity.

Bottom-up (investing): Bottom-up fund managers build portfolios by focusing on the analysis of individual securities rather than broader macroeconomic or market factors in order to identify the best opportunities in an industry, country, or region; the opposite of top-down investing.

Basis point (bp): One basis point equals 1/100 of a percentage point. 1 bp = 0.01%, 100 bps = 1%.

Capital: When referring to a portfolio, the capital reflects the net-asset value of a fund. More broadly, it can be used to refer to the financial value of an amount invested in a company or an investment portfolio.

Cash flow: The net balance of cash that moves in and out of a company. Positive cash flow shows more money is moving in than out, while negative cash flow means more money is moving out than into the company.

Discount: Refers to a situation when a security is trading for lower than its fundamental or intrinsic value. The opposite of trading at a premium.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.