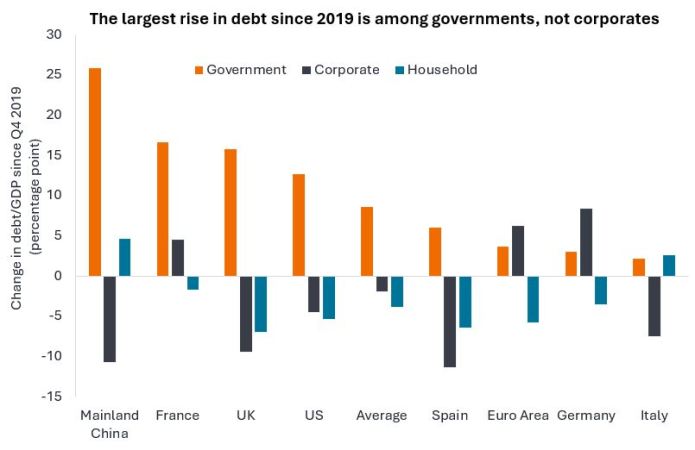

Source: HSBC, BIS, IIF, national statistical agencies. Until Q4 2024, except governments (Q3 2024) and corporates and households for UK and China (Q3 2024). Gross domestic product (GDP) is a measure of the size of the economy.

Companies spent much of the last few years repairing their balance sheets, aided by relatively strong earnings. In some ways the resilience of corporates is partly related to the largesse of governments. The chart above shows the shift in debt burden towards governments and generally away from corporates and households.

In the US, the passing of the Big Beautiful Bill Act is forecast to add an additional US$2 trillion to US government borrowing between 2025-29.1 In the UK, tax raising has been offset by higher welfare spending and public sector pay. In Germany, the government has proposed a big increase in infrastructure and defence spending. Anything that increases spending in the economy is likely to be supportive for corporates. Earnings have been robust and credit spreads (the difference in yield between a corporate bond and a government bond of similar maturity) are near their lows as companies, on average, have reasonably healthy finances.2 In contrast, heavy government borrowing is leading to questions around debt sustainability and has contributed to yields on government debt (particularly longer-term debt of 10+ years to maturity) remaining high.

The question for markets is will governments seek to balance revenues and spending any time soon? On one side of the ledger, lower borrowing might bring down government bond yields, on the other side, it might remove a useful stimulant to the economy. For now, corporate credit is happy for governments to keep the spending taps open.

Movements in government bond yields can affect returns in credit markets so we need to pay attention to factors such as debt levels that can affect yields. Corporate bond markets have performed well in recent years and there has been strong appetite for credit from investors seeking a yield pick-up over government bonds. With credit spreads at relatively low levels, however, this leaves less margin for error, so we believe it is increasingly important to be selective about which credits to hold in a portfolio.

– James Briggs, Fixed Income Portfolio Manager.

1Source: US Congressional Budget Office, estimate effects, 29 June 2025.

2Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA, Morgan Stanley, credit spreads to governments, range over the last 20 years, 28 July 2025. Past performance does not predict future returns.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

Balance sheet: A financial statement that summarises a company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity at a particular point in time. It is called a balance sheet because of the accounting equation: assets = liabilities + shareholders’ equity.

Corporate bond: A bond issued by a company. Bonds offer a return to investors in the form of periodic payments and the eventual return of the original money invested at issue on the maturity date.

Coupon: A regular interest payment that is paid on a bond, described as a percentage of the face value of an investment. For example, if a bond has a face value of $100 and a 5% annual coupon, the bond will pay $5 a year in interest.

Credit spread: The difference in yield between securities with similar maturity but different credit quality. Widening spreads generally indicate deteriorating creditworthiness of corporate borrowers, and narrowing indicate improving.

Default: The failure of a debtor (such as a bond issuer) to pay interest or to return an original amount loaned when due.

Maturity: The maturity date of a bond is the date when the principal investment (and any final coupon) is paid to investors. Shorter-dated bonds generally mature within 5 years, medium-term bonds within 5 to 10 years, and longer-dated bonds after 10+ years.

Yield: The level of income on a security over a set period, typically expressed as a percentage rate. For a bond, at its most simple, this is calculated as the coupon payment divided by the current bond price.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- The Fund invests in high yield (non-investment grade) bonds and while these generally offer higher rates of interest than investment grade bonds, they are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- Emerging markets expose the Fund to higher volatility and greater risk of loss than developed markets; they are susceptible to adverse political and economic events, and may be less well regulated with less robust custody and settlement procedures.

- If a Fund has a high exposure to a particular country or geographical region it carries a higher level of risk than a Fund which is more broadly diversified.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- If the Fund holds assets in currencies other than the base currency of the Fund, or you invest in a share/unit class of a different currency to the Fund (unless hedged, i.e. mitigated by taking an offsetting position in a related security), the value of your investment may be impacted by changes in exchange rates.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.

- In addition to income, this share class may distribute realised and unrealised capital gains and original capital invested. Fees, charges and expenses are also deducted from capital. Both factors may result in capital erosion and reduced potential for capital growth. Investors should also note that distributions of this nature may be treated (and taxable) as income depending on local tax legislation.