Search for diversification keeps EMD HC in the limelight

Global market sentiment entering 2026 builds on 2025’s strong foundation, marked by robust emerging markets hard currency debt (EMD HC) performance and a weaker US dollar as investors diversified away from US-centric policy uncertainty. Traditionally a headwind for EM, uncertainty now signals a paradigm shift: recent US-centric volatility – highlighted by the ‘Liberation Day’ tariff announcement – has spurred a global search for diversification that is likely to persist.

Uncertainty appears to have weighed more heavily on the US than on the rest of the world, signalling that markets are beginning to differentiate between types of volatility rather than reflexively treating EM as the weakest link. This evolution suggests the traditional safe-haven response is changing, with EM debt no longer held hostage to every bout of global risk aversion – a positive structural development for the asset class. Recent resilience in the asset class reinforces confidence in its ability to navigate volatility.

Global outlook: Cruise control and ‘soft’ landings

The global economic outlook for 2026 appears broadly stable, supported by past monetary easing and resilient private sector balance sheets. Uncertainty around US trade policy is expected to subside as both China and the US seek to limit economic disruption, reducing a key source of volatility. The US economy, in particular, benefits from an AI-capex boom, potential de-regulation and a modestly positive fiscal impulse, though questions linger over the sustainability of growth. The US Federal Reserve is likely to ease policy further, but sticky inflation could keep the easing cycle shallow. With midterm elections approaching in late 2026, political pressure on the Federal Reserve and fiscal policy could intensify, leaving the Fed stuck between a rock and a hard place if it faces a ‘too hot’ economy.

Europe faces structural and geopolitical challenges, including supply chain vulnerabilities and competitive pressures from Chinese manufacturing, but targeted fiscal spending – particularly in Germany – should provide support for European growth. Persistent political fragmentation, however, limits the region’s efforts to respond cohesively. Finally, an end to the war in Ukraine could have significant implications for global inflation, growth and commodity prices while easing geopolitical risks and lifting investor sentiment.

China’s outlook for 2026 reflects a delicate balancing act: stabilising growth amid a prolonged property sector weakness and redirecting excess industrial capacity to markets outside of the US, raising the risk of trade frictions. Fiscal stimulus will generally be targeted rather than a large-scale “bazooka”. Authorities aim to maintain a growth target near 5%, relying on advanced manufacturing and technology investment to offset sluggish consumption and structural reform needs.

Key risks for 2026 are largely US-centric: a US recession amid a K-shaped economy[1], sticky inflation, elevated US equity market valuations (with high household exposure to these) and renewed trade tensions. The K-economy implies that the US outlook includes both a surprisingly strong economy and a potentially recessionary one. Tariffs are likely to be modestly inflationary in the US and slightly deflationary elsewhere. While policy momentum offers clarity early in the year, expectations then diverge as inflation trends and their impact on Federal Reserve decisions become pivotal.

Emerging markets enter 2026 with resilience, policy flexibility, and attractive yield

EM enter 2026 on a constructive footing, showing resilience amid global challenges. Improved policy frameworks, credible monetary and fiscal consolidation since the Covid era have anchored inflation expectations, allowing gradual monetary easing. Fiscal policy is broadly returning to neutral, contrasting with developed markets (DM), where fiscal pressures continue to build.

Growth drivers for EM should be more domestic than external, supported by structural trends such as friend-shoring led investment. With the US Dollar expected to be weaker-to-rangebound, most EM central banks can focus on their local cycles without significant FX pressure, reinforcing policy flexibility.

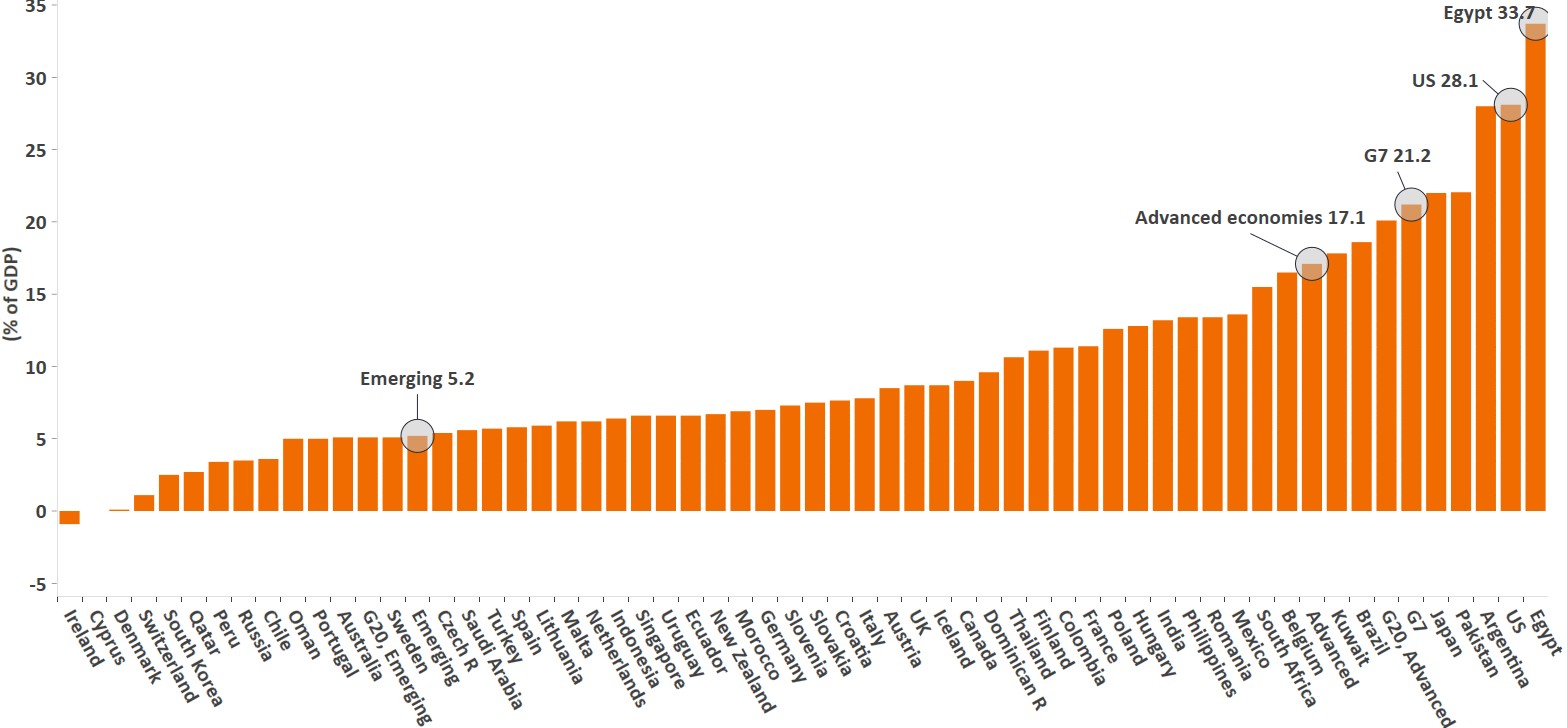

The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) projected rising interest-growth differential over the next five years highlights mounting fiscal pressures globally – higher funding costs and slower growth – across both EM and DM. Emerging economies, however, enjoy a buffer from higher nominal growth relative to funding costs, supporting debt sustainability, while the US and other advanced economies face a much narrower gap, signalling greater fiscal strain ahead.

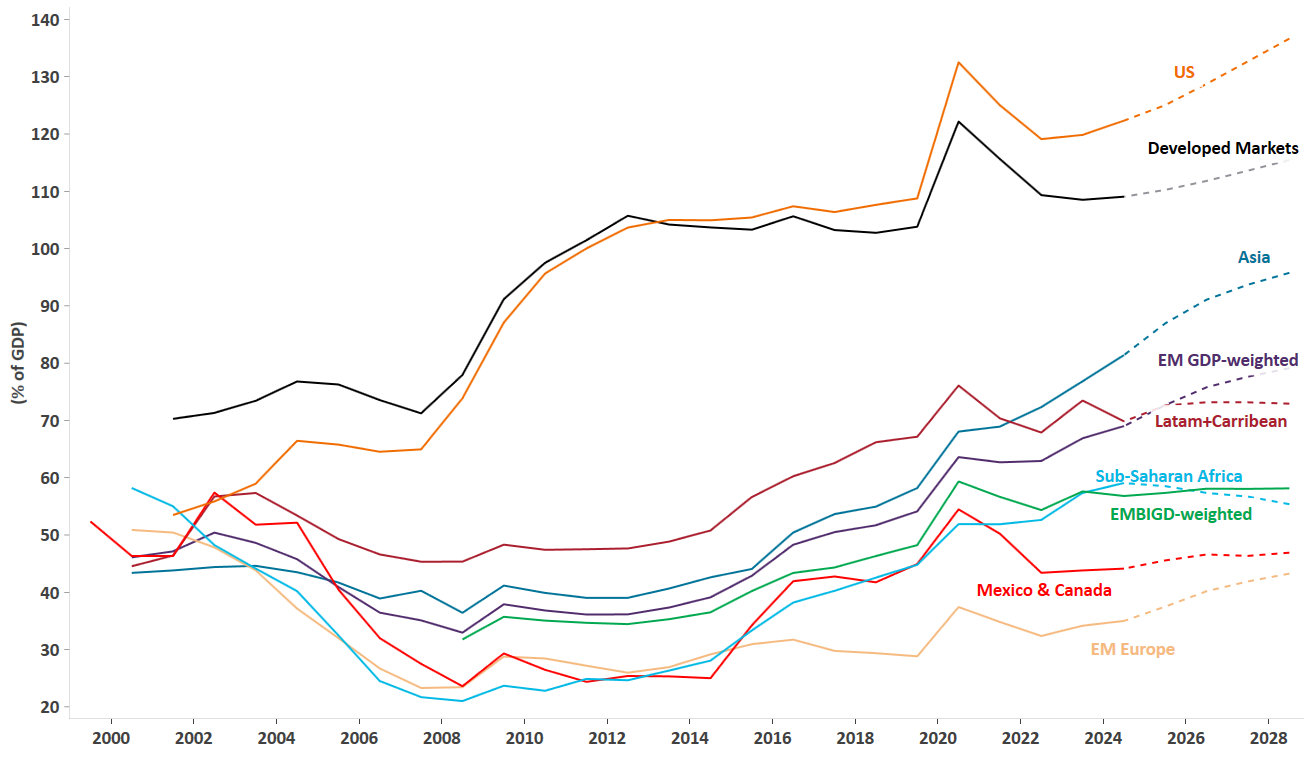

Fiscal risks remain elevated in DMs, where limited appetite for needed fiscal adjustments compounds fragility as debt levels reach historic highs – gross financing needs surged in 2025, particularly in DM, with debt climbing above 110% of GDP compared to just below 60% of GDP for EM in EMBIGD-weighted terms (Figure 1). In a world of higher funding costs, elevated debt burdens constrain fiscal space and risk crowding out private sector borrowing, posing a medium-term challenge for global growth, especially for major DMs. Collectively, these factors justify a lower risk premium for EMD HC and highlight its appeal as a source of diversification and attractive yield in a world where DM fiscal fragility casts a long shadow.

Figure 1: Global debt reaches concerning levels

General Government Gross Debt

Source: Janus Henderson, JP Morgan and Macrobond, as at 15 December 2025. EMBIGD-weighted is EM weighted by countries as represented in the JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index. EM GDP weighted by nominal GDP in market FX. There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Figure 2: Debt dynamics are becoming more challenging

Gross financing need 2025

Source: Janus Henderson, Macrobond, as at 15 December 2025.

Are emerging markets well-positioned for the AI-boom?

Emerging markets are uniquely positioned to benefit from new technologies, as dominant suppliers of critical commodities for electric vehicles, renewable energy infrastructure, energy storage, and advanced manufacturing. This resource advantage provides a strategic growth lever as demand for these materials accelerates. Beyond commodities, this positioning enhances resilience and creates opportunities for deeper integration into global value chains tied to clean energy and high-tech sectors.

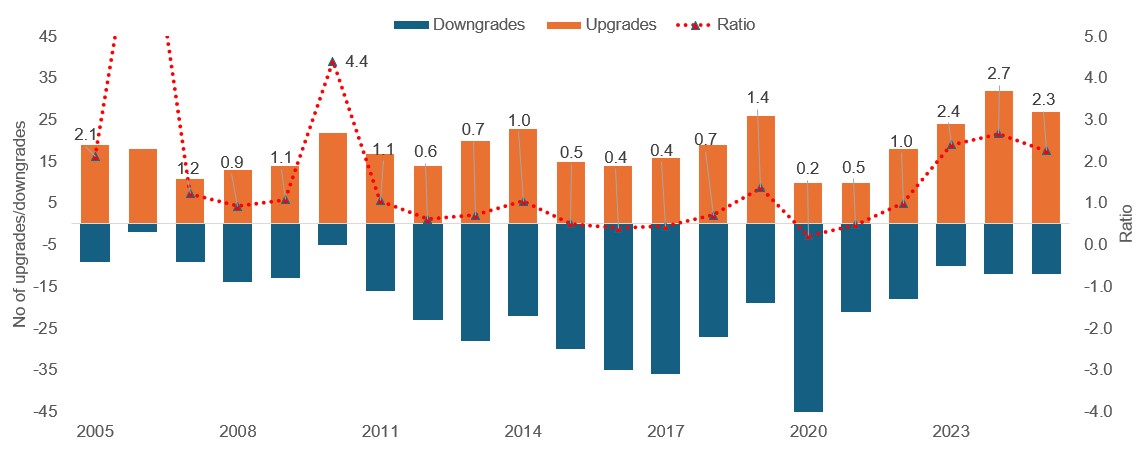

Ratings outlook for EM: Upgrades outpace downgrades as fiscal discipline pays off

EM credit quality has already improved substantially with more than double as many rating upgrades as downgrades in the last three years, while the number of downgrades has come down considerably. In 2025, we saw two countries regaining their investment grade/IG status – Azerbaijan and Oman – while a few others (Paraguay, Serbia and Morocco) are expected to “graduate” to IG for the first time. More ratings upgrades than downgrades are expected in 2026, particularly among high yield (HY) or frontier markets, reflecting successful fiscal adjustment, implementation of IMF-led policies as well as post-Covid strong growth dynamics. While several IMF programmes will expire in 2026, graduation for countries having met programme targets signals successful reform, while more fragile nations may have to seek continued support.

Figure 3: EM ratings upgrade cycle continues

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, as at 15 December 2025.

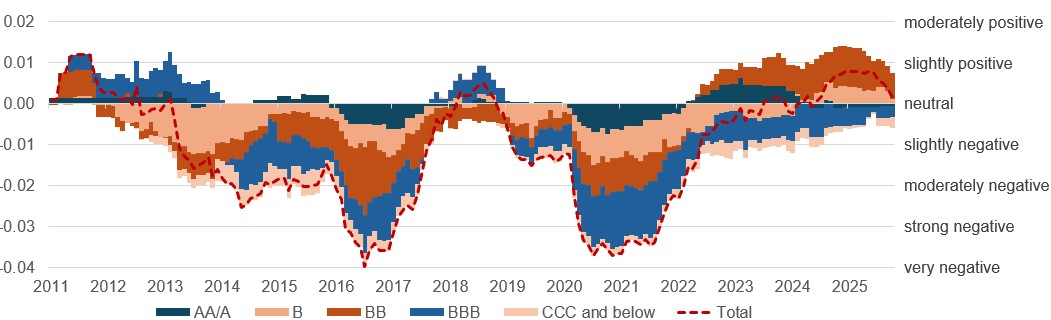

Figure 4: HY countries improving the most

Net outlook breakdown

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, JP Morgan, as at 15 December 2025. Ratings of the JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index.

Tight spreads, strong fundamentals: Why EM debt stands out in 2026

The relative attractiveness of EMD HC is strengthening as fundamentals in DMs deteriorate. While spreads are near historical tights, valuations appear justified by stronger credit profiles, greater diversification, and structural resilience – these support a new equilibrium of lower risk premiums rather than a temporary anomaly.

Comparing EMD HC to US corporate credit highlights diverging issuance dynamics. While EM sovereign issuance is expected to remain healthy (as it was in 2025), overall supply – and especially net supply – should decline. Issuers are increasingly looking to diversify and reduce funding costs, which we expect to extend into 2026. With US tariffs curbing exports and dollar inflows, many issuers are redirecting funding away from the US toward other markets, aligning debt profiles with a more multipolar global economy. US corporate issuance is expected to be more significant, driven partly by significant AI-related capex, creating credit spread pressure. For EM high-yield issuers, elevated funding costs will likely limit activity to refinancing rather than new borrowing, further tightening net supply and supporting valuations.

Despite renewed interest in 2025, EM fixed income allocations remain modest, leaving room for rebalancing as investors seek diversification and yield. With improving fundamentals and a supportive technical backdrop, there is strong potential for sustained inflows over the coming years. The elevated yield-level has in recent attracted more yield-sensitive buyers, amplifying positive technicals even as spreads remain tight. Cumulative flows into dedicated EM bond funds turned positive in 2025[2].

EM Debt: a ‘Goldilocks’ opportunity amid global shifts

The outlook for EMD HC in 2026 remains constructive, supported by resilient fundamentals, favourable technicals, a conducive external environment and attractive income potential. Central banks paths will diverge – with some DMs even expected to hike while most others ease. A ‘not too hot, not too cold’ US economy and a contained dollar create near “Goldilocks” conditions for EM. Improving EM fundamentals make EM assets more resilient to a more hawkish Fed or even a moderate acceleration in the US economy.

Although valuations are tight and returns may moderate, EMD HC stands out as a source of diversification, reinforced by stronger credit quality and a shifting global risk profile. Strong commodity linkages, credible policy frameworks, and healthier balance sheets reinforce its appeal.

Looking ahead, total returns should be driven primarily by high carry and selective spread compression, particularly in high-yield countries. Even in a US recession scenario, downside risks are mitigated by the long duration profile of the asset class which benefits from falling Treasury yields. On the political front, Latin America has some big elections coming up in 2026: Brazil, Colombia and Peru, which we are closely watching.

Our focus is on idiosyncratic country and security opportunities, high carry and improving credit stories within high yield, where selective upgrades and strong fundamentals can drive alpha. We also favour issuers with defensive characteristics, providing a resilient backbone in an environment where valuations leave little margin for error.

Diversification neither assures a profit nor eliminates the risk of experiencing investment losses.

High-yield or “junk” bonds involve a greater risk of default and price volatility and can experience sudden and sharp price swings.

Sovereign: Typically refers to debt issued by a national government. Sovereign bonds are backed by the country’s creditworthiness and ability to repay.

Emerging market investments have historically been subject to significant gains and/or losses. As such, returns may be subject to volatility.

Sovereign debt securities are subject to the additional risk that, under some political, diplomatic, social or economic circumstances, some developing countries that issue lower quality debt securities may be unable or unwilling to make principal or interest payments as they come due.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

Foreign securities are subject to additional risks including currency fluctuations, political and economic uncertainty, increased volatility, lower liquidity and differing financial and information reporting standards, all of which are magnified in emerging markets.

Volatility measures risk using the dispersion of returns for a given investment.

J.P. Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index (EMBIGD) tracks liquid, US Dollar emerging market fixed and floating-rate debt instruments issued by sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities.

Footnotes

[1] K-shaped economy concerns for the US stem from labour market and consumer weakness running parallel to strong capex and how new AI implementation can affect the labour market.

[2] Source: Barclays, EPFR, December 2025. Cumulative flows since February 2017 into all dedicated EM bond funds.

Alpha: Alpha is the difference between a portfolio’s return and its benchmark index after adjusting for the level of risk taken. This measure is used to help determine whether an actively-managed portfolio has added value relative to a benchmark index, taking into account the risk taken. A positive alpha indicates that a manager has added value.

Balance sheets: A financial statement that summarises a company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity at a particular point in time. Each segment gives investors an idea as to what the company owns and owes, as well as the amount invested by shareholders. It is called a balance sheet because of the accounting equation: assets = liabilities + shareholders’ equity.

Capital expenditure (capex): Funds used by a company to acquire, upgrade, and maintain physical assets such as property, plants, buildings, technology, or equipment. These expenditures are often necessary for long-term investments that help a business grow or maintain its operations.

Carry: Return earned from a security assuming its price remains unchanged. For a bond, carry is essentially the income generated by the bond less the cost of financing.

Credit: Credit is typically defined as an agreement between a lender and a borrower. It is often narrowly used to describe corporate borrowings, which can take the form of corporate bonds, loans, or other fixed-interest asset classes.

Credit rating: An independent assessment of the creditworthiness of a borrower by a recognised agency such as Standard & Poors, Moody’s, or Fitch. Standardised scores such as ‘AAA’ (a high credit rating) or ‘B’ (a low credit rating) are used, although other agencies may present their ratings in different formats. Credit quality is similar as a measure of the financial solvency of an individual or an entity such as a company or a government.

Credit spread: The difference in yield between securities with similar maturity but different credit quality, often used to describe the difference in yield between corporate bonds and government bonds. Widening spreads generally indicate a deteriorating creditworthiness of corporate borrowers, while narrowing indicates improving.

Deflationary: A decrease in the price of goods and services across the economy, usually indicating that the economy is weakening. It differs from ‘disinflation’, which implies a decrease in the level of inflation. Deflation is the opposite of inflation.

Duration: Duration can measure how long it takes (in years) for an investor to be repaid a bond’s price by the bond’s total cash flows. Duration can also measure the sensitivity of a bond’s or fixed-income portfolio’s price to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates, and vice versa.

External environment: The set of conditions, such as political, economic, social, and technological factors, that exist outside an organisation and can influence its operations and strategy.

Fiscal consolidation: Policies implemented by governments to reduce debt accumulation and minimise deficits through increased revenue or reduced expenditure to ensure long-term economic stability.

Fiscal impulse: The change in a government’s budget balance driven by fiscal policy (spending and taxes), used to assess if policy is expansionary, neutral, or contractionary and its effect on economic growth.

Fiscal policy: Describes government policy relating to setting tax rates and spending levels. Fiscal policy is separate from monetary policy, which is typically set by a central bank. Neutral fiscal policy means the government isn’t actively trying to boost (expansionary) or slow (contractionary) the economy.

Fiscal spending: Government expenditure on goods, services, and public projects aimed at influencing economic activity and achieving policy objectives.

Fiscal expansion/ stimulus: This refers to an increase in government spending and/or a reduction in taxes.

Fundamentals: In reference to sovereigns (countries or their central governments), fundamentals are the key economic, fiscal, and institutional variables that determine a nation’s ability and willingness to service its debt.

Funding costs: The expenses incurred by governments or corporations when raising capital, such as interest paid on debt or dividends paid on equity.

Goldilocks: An economic scenario marked by moderate growth and low inflation—ideal conditions for stable markets, neither too hot (inflationary) nor too cold (stagnant).

Gross domestic product (GDP): The total monetary value of all final goods and services produced within a country in a given period, used to gauge economic health and size. Nominal growth: Economic growth measured in current prices without adjusting for inflation; combines real growth and inflation. Nominal GDP in market FX is the value of a country’s total economic output in a specific period, measured using current market prices and then converted into a common currency (usually the US dollar) using the prevailing foreign exchange (FX) market rates.

Hawkish: An indication that policy makers are looking to tighten financial conditions, such as by supporting higher interest rates to curb

inflation.

Idiosyncratic risk: Factors that are specific to a particular company and have little or no correlation with market risk.

Inflation: The rate at which the prices of goods and services are rising in an economy. The consumer price index (CPI) and retail price index (RPI) are two common measures; the opposite of deflation.

Issuance: This refers to the process where a company, government, or other entity creates and offers new financial instruments, such as stocks or bonds, for sale to investors Net supply refers to the total amount of new securities issued by governments or corporations minus any redemptions, representing the net addition to market supply.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. Monetary policy tools include setting interest rates and controlling the supply of money. Monetary stimulus refers to a central bank increasing the supply of money and lowering borrowing costs. Monetary tightening refers to central bank activity aimed at curbing inflation and slowing down growth in the economy by raising interest rates and reducing the supply of money.

Recession: A sustained decline in economic activity, usually perceived as two consecutive quarters of economic contraction.

Risk aversion: A preference for lower-risk investments; investors exhibiting risk aversion require higher expected returns to compensate for assuming greater risk.

Risk premium: The additional return an investment is expected to provide in excess of the risk-free rate. The riskier an asset is deemed to be, the higher its risk premium to compensate investors for the additional risk.

Safe haven: An asset that is expected to retain its value or potentially gain value during periods of economic uncertainty or market turbulence (e.g., gold, US government debt, the US dollar, cash, etc.).

Spread compression: A decrease in credit spread, indicating improving credit conditions or narrowing yield differences between riskier and safer bonds.

Technicals: The analysis of market action based on price and volume data, trends, and momentum, typically used to predict future price movements.

Total returns: The combined return from an investment, including capital appreciation and income (such as interest or dividends), expressed as a percentage of initial investment.

Value chains: The full range of activities and processes involved in producing goods or services, from initial conception to distribution to customers.

Volatility: The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security, or index, moves up and down. If the price swings up and down with large movements, it has high volatility. If the price moves more slowly and to a lesser extent, it has lower volatility. The higher the volatility, the higher the risk of the investment.

Yield: The level of income on a security over a set period, typically expressed as a percentage rate. For a bond, this is calculated as the coupon payment divided by the current bond price.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall. High yielding (non-investment grade) bonds are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- Emerging markets expose the Fund to higher volatility and greater risk of loss than developed markets; they are susceptible to adverse political and economic events, and may be less well regulated with less robust custody and settlement procedures.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- The Fund may incur a higher level of transaction costs as a result of investing in less actively traded or less developed markets compared to a fund that invests in more active/developed markets.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.