Janus Henderson shares its name with the classical Roman god of duality, so it is interesting that today’s bond market seems to be facing in different directions. On one side, we have shorter-dated bonds that are responding to near-term monetary policy. On the other side, longer-dated bonds, those with ten years or more to maturity, appear to be moving wholly independently of their shorter-dated counterparts, and for that matter, economic data. What could be causing this duality and what might it mean for investors?

Differing yield directions

2025 was another year in which the sheer resilience of global growth surprised consensus and defied economists who were focused on the tail risk of recession. Despite the collapse in sentiment in April 2025 associated with Liberation Day tariff announcements (Goldman Sachs April 2025: 45% chance of US recession)1, the consumer proved relatively unaffected. Businesses slowed hiring but did not increase lay-offs, whilst structural themes of increased investment associated with artificial intelligence (AI) and the energy transition continued or accelerated. The debate of hard versus soft landing for the economy which followed the aggressive rate hikes in 2022-23 was definitively decided in favour of soft landing.

As a result, the rate cuts which began in mid-2024 across the developed world largely petered out in 2025 with only the US and UK still pricing in the possibility of some further reductions. The common theme across central banks was that these cuts were presented as adjustments towards a less restrictive / a return to “neutral” stance of monetary policy. In no country did central banks argue for a stimulatory stance for interest rates. This is understandable given that inflation has struggled to return to 2% in many countries, and in the case of the UK defied expectations at the beginning of the year for a decline to 2.5%, instead averaging 3.4% through 2025.2

The big surprise for bond markets during this 18-month plus period of rate cuts (ex-Japan which continued its glacial rate hiking) was simply that longer-dated bond yields did not fall. What should, on paper, have been a clear cyclical catalyst for strong bond market returns (falling bond yields = rising prices), failed to materialise.

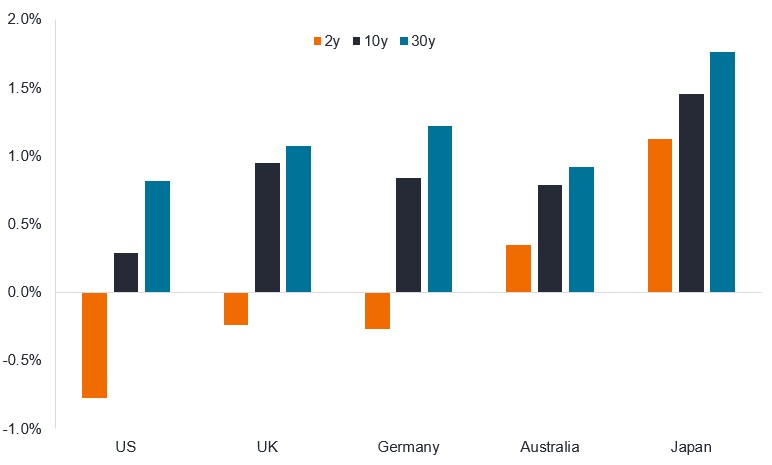

Figure 1: Yield change at different maturity points since end 2023

Change in yield among government bonds (%)

Source: Bloomberg, government bond yields for respective countries and maturities, 2-year, 10-year and 30-year bonds, difference between yield at 31 December 2023 and at 31 December 2025. Yields may vary over time and are not guaranteed.

For the US bond market in particular, using data all the way back to the 1960s, this was the one historical example in which rate cuts did not drive 10-year benchmark bond yields lower.3 If a market fails to perform despite a clear cyclical tailwind, this may well be providing investors with a longer-term structural “tell” about the outlook for this market.

Resistance to falls

The reasons for this are much debated but remain inconclusive: worries about elevated levels of government borrowing; fewer price-insensitive buyers as central banks have moved from being net buyers of government debt through quantitative easing to net sellers via quantitative tightening; and residual inflation concerns are potential factors.

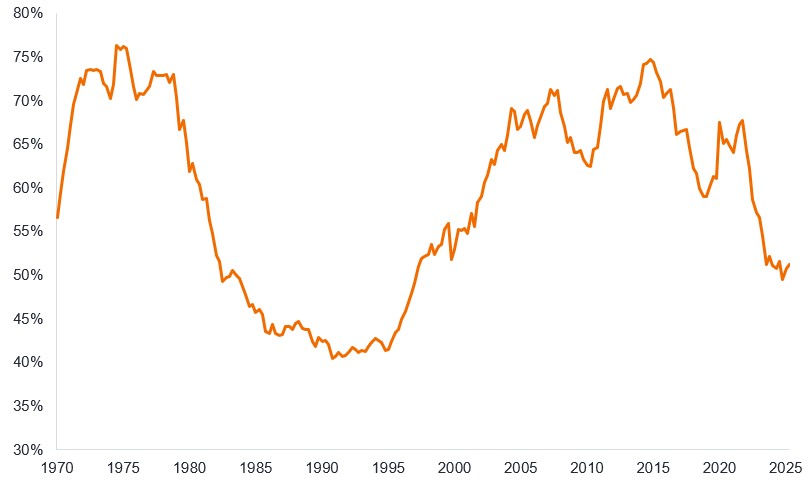

Figure 2: Price-insensitive buyers as a % of US Treasury debt has declined recently

Source: JP Morgan, FRED, Janus Henderson Investors. Price insensitive buyers include US Federal Reserve System Open Market Accounts (SOMA), US commercial banks and foreign combined holdings, Q1 1970 to Q3 2025. Price-insensitive buyers may purchase Treasuries for reasons other than an investment return motive, e.g. to support monetary policy or to meet regulatory rules on capital.

However, there is no doubt that the structural economic shifts post-Covid have been detrimental for the broader supply-demand balance of global bond markets.

Anchors aweigh: Low-yield markets moving higher

In particular, it is worth focusing on the two low-yielding global bond market anchors of Japan and Germany (a proxy for Europe). These have been transitioning back to providing yield opportunities for the first time in many years.

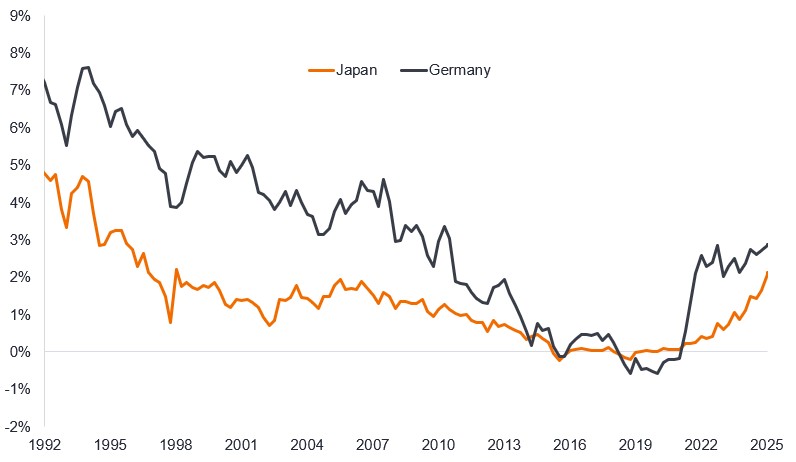

Figure 3: New direction

Japan and German 10-year government bond yields (%)

Source: Bloomberg, 31 December 1992 to 5 January 2026. Yields may vary over time and are not guaranteed.

Japan has, in recent years, emerged with a serious labour shortage, structural wage inflation and is in the process of transitioning away from a multi-decade period of zero interest rates. The presentation and remarks from Bank of Japan Governor Ueda on the Japanese labour market during the Jackson Hole Symposium in August 2025 are well worth re-reading and reflecting upon. Meanwhile the European Union used the Covid-crisis as a Hamiltonian-opportunity4 to issue joint bonds which five years later total €738bn at 31 Dec 20255 in size (about half the size of the German government federal bond market).6 In addition, Germany announced a €1 trillion Euro multi-year fiscal spending spree in March 2025, whilst the broader labour market in Europe sees unemployment close to its lowest levels in three decades.7

Without these anchors of low-yielding government bond markets, even the cyclical tailwinds of interest rate cuts have not translated into lower global bond yields among longer-dated bonds. Instead, a rangebound period for bond yields has persisted for the last few years in many markets. At the end of 2025, the bond market saw ripples of concern about the prospect of interest rate increases in smaller economies: Australia, Sweden, New Zealand and Canada all saw hikes begin to be priced as a probability in 2026.8

The sharp rise in bond yields that resulted in these countries in late 2025 was a salient warning about what may occur if hiring eventually follows resilient growth and shows signs of a pick-up again.

Please see our earlier article on this subject: “Sobering developments in developed world rates markets”.

1Source: Goldman Sachs, Tariff-induced recession risk, 17 April 2025.

2Source: UK Consumer Price Index, average for 11 available months of data for 2025, 9 January 2026.

3Source: FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data), Janus Henderson calculations, 10-year US Treasury yields and US Federal Funds policy rate, 31 Dec 1966 to 31 Dec 2025. The yield on 10-year US Treasuries has remained higher than the level it was at when the most recent US rate cutting cycle began on 18 September 2024.

4Hamiltonian opportunity: The 1790 decision by Alexander Hamilton, the first US Secretary of the Treasury, to issue federal securities (US Treasuries), backed by federal revenues, laying the foundation for the US financial system.

5Source: European Commission, outstanding amount of EU bonds and EU bills as at 31 December 2025.

6Source: Bundesrepublik Deutschland Finanzagentur, German Federal Bonds total €1,383bn (Bunds + Inflation Linked Federal Securities), at 7 January 2026.

7Source: Eurostat, Eurozone unemployment rate, seasonally adjusted was 6.3% for November 2025, only just above the low of 6.2% over the 30 years from January 1995.

8Source: Bloomberg, World interest rate probability, 8 December 2025.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

Anchors aweigh: A term used to signify the raising of a ship’s anchor.

Credit risk: The sensitivity of a company or a portfolio to economic and corporate conditions. Credit risk is the risk that a borrower will default on its contractual obligations to make the required interest payments or repay the loan. If a bond or portfolio has high credit risk, it may perform well when economic conditions are favourable but underperform if economic and corporate conditions sour.

Cyclical: Something that occurs in cycles, often describing the fluctuations (ups and downs) in the economy or interest rates over time.

Default: The failure of a debtor (such as a bond issuer) to pay interest or to return an original amount loaned when due.

Duration: Duration measures the sensitivity of a bond’s or fixed income portfolio’s price to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates and vice versa.

Federal Reserve (Fed): The central bank of the US that sets monetary policy for the US.

Fiscal/Fiscal policy: Describes government policy relating to setting tax rates and government spending and borrowing.

Hard landing: A situation in which measures to bring down inflation lead to negative economic growth and a rise in unemployment.

Hawkish: An indication that policy makers are looking to tighten financial conditions, such as by supporting higher interest rates to curb inflation. The opposite of dovish, which describes policymakers loosening policy, i.e. cutting interest rates to stimulate the economy.

Inflation: The rate at which prices of goods and services are rising in the economy.

Interest rate cycle: The interest rate cycle reflects the fluctuation of interest rates over time. It is typically linked to the economic cycle as central banks alter monetary policy in response to economic conditions.

Maturity: The maturity date of a bond is the date when the principal investment (and any final coupon) is paid to investors. Shorter-dated bonds generally mature within 5 years, medium-term bonds within 5 to 10 years, and longer-dated bonds after 10+ years.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. Monetary policy tools include setting interest rates and controlling the supply of money. Monetary easing or stimulus refers to a central bank increasing the supply of money and lowering borrowing costs. Monetary tightening refers to central bank activity aimed at curbing inflation and slowing down growth in the economy by raising interest rates and reducing the supply of money.

Neutral rate: The interest rate level at which monetary policy is neither expansionary nor contractionary, i.e. one where the economy is at full employment with stable inflation.

Price-insensitive buyers: Here this relates to buyers of Treasuries who may purchase Treasuries for reasons other than an investment return motive, e.g. to support monetary policy or to meet regulatory rules on capital.

Quantitative easing: The central bank creates money to buy bonds, easing monetary conditions in the economy; quantitative tightening is where the central bank decreases the money supply either by selling government securities or letting them mature and removing them from its balance sheet.

Recession: A sustained decline in economic activity, usually perceived as two consecutive quarters of economic contraction.

Soft landing: A situation in which a central bank succeeds in bringing down inflation without significantly harming employment and economic growth levels.

Structural: An economic condition arising when an industry or market changes how it functions or operates. This could be attributed to new economic development, shifts in the pools of capital and labour, demand and supply of natural resources, political and regulatory change, taxation, etc.

Tail risk: Tail risk events are those that have a small probability of occurring, but which could have a significant effect on performance were they to arise.

US Treasury securities: Direct debt obligations (bonds) issued by the US Government and backed by the US government.

Yield: The level of income on a security over a set period, typically expressed as a percentage rate.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.