JH Explorer: Brazil navigates rough economic seas

Portfolio Manager Daniel Graña recently travelled to Brazil to assess how the country is navigating a high-rate, low-growth environment while concurrently attempting to restore a framework that would instill fiscal discipline.

7 minute read

Key takeaways:

- Brazil’s economy is dealing with the one-two punch of a credit-fueled consumption hangover and some of the highest inflation-adjusted interest rates in the world.

- The country is attempting to navigate these waters while at the same time instilling the fiscal discipline necessary to avert repeated crises and gain the confidence of global investors.

- While the new fiscal rule has its vulnerabilities and Brazil faces near-term headwinds, the country is also home to several innovative companies catering to a large domestic population that is hungry for increasingly sophisticated products and services.

| The JH Explorer series follows our investment teams across the globe and shares their on-the-ground research at a country and company level. |

It has long been our opinion that the most optimal way to view the emerging market (EM) equities landscape is through the complementary lenses of country, company, and governance. All require deep research, and none can be entirely carried out from a distant office. An investor must be on the ground to understand the policies that impact an economy and hear directly from business leaders about how they intend to navigate a complex marketplace with the aim of growing earnings.

It’s for these reasons that I traveled to Brazil earlier this year to learn how the country and its corporations are faring under higher interest rates and slowing growth, and to assess the government’s new fiscal rules’ chances for success in stabilizing the country’s sometimes unruly fiscal situation.

A pivotal country in a pivotal period

With its large population and abundance of natural resources, Brazil rightly commands a place in EM equity allocations. But the country has a complicated history of fiscal management, which has resulted in numerous crises.

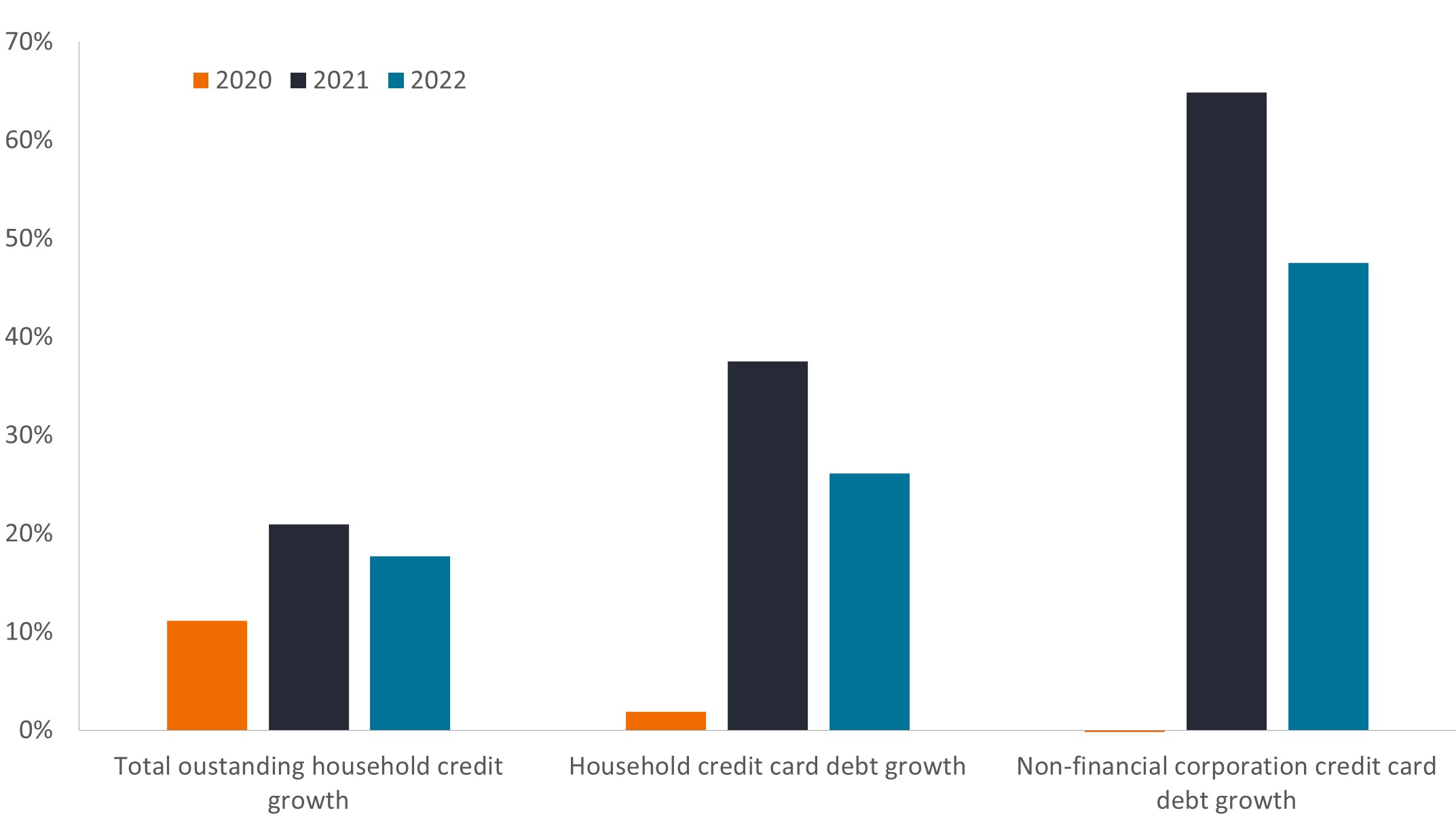

As with other countries, Brazil’s COVID-era stimulus programs resulted in myriad economic distortions that must now be sorted out. Brazil’s fiscal largesse in the wake of the pandemic was among the most generous in the developing world, with much of it geared toward stimulating consumption. A permissive regulatory framework allowed for the rapid expansion of fintech companies, which provided credit access to previously underbanked segments of the population. Between 2018 and 2022, the number of bank accounts per economically active person rose from 2.2 to 5 – far higher than in Latin American peers. Consequently, credit card debt exploded, climbing by 65% and 47% in 2021 and 2022, respectively.

Brazilian annual outstanding credit growth by category

All facets of the economy took advantage of low rates and novel credit platforms rolled out during the pandemic with the aim of increasing debt-financed consumption and investment.

Source: Bloomberg, Central Bank of Brazil, as of 31 December 2022.

The hangover

Brazil is now dealing with the aftereffects of its credit excesses, including the air pocket that inevitably forms when consumption is pulled forward to such a degree. Debt service ratios have climbed to over 28% and the total household debt to GDP ratio sits just below 50%, up from 39.3% prior to the pandemic.

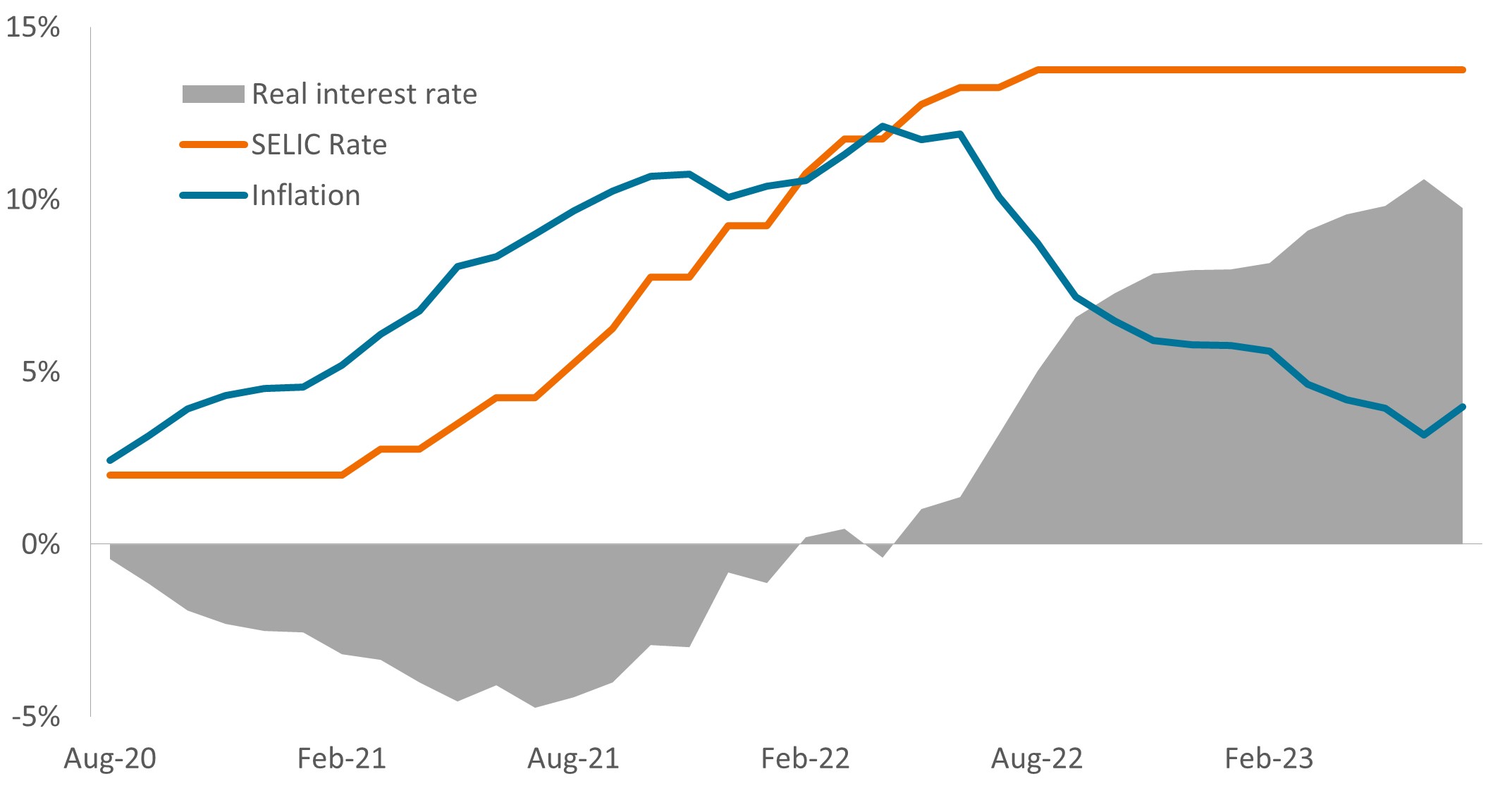

Further aggravating the situation was Brazil not being immune to the recent global wave of inflation caused by pandemic-driven supply chain disruptions and Russia’s war in Ukraine. Unlike developed markets, EM central banks did not have the luxury of making a “transitory” inflation call then hoping for the best. Understanding all too well the pernicious nature of inflation, the Central Bank of Brazil aggressively raised its policy rate by nearly 1,200 basis points, resulting in the country having among the world’s highest real interest rates.

Brazil’s benchmark policy rate, inflation, and real interest rate

With inflation’s surge beginning early in Brazil, the country’s central bank was among the world’s most aggressive in tightening policy, resulting in real interest rates climbing above 11%.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 31 July 2023.

The higher cost of capital was the second blow to an economy already teetering due to weakening consumption. Our analysis indicates that when excluding the energy, agricultural, and mining sectors, the remainder of Brazil’s economy is already in recession. Nonperforming loans on the country’s banks’ books are rising and loan growth is slowing. Had debt capital markets not frozen, loan growth would likely already be negative.

Voices from the trenches

The mood of corporate executives with whom I met was somber. Such interactions, in our view, provide some of the most candid commentary on an economy’s near- to mid-term prospects, as these are the decision makers that must allocate capital and make other strategic decisions in the face of gathering headwinds. Given the economic uncertainty and high borrowing costs, bank executives spoke of slowing credit demand. On the supply side, banks are shunning riskier borrowers.

Executives at consumer-focused businesses are dealing with the fallout from the credit binge. One commented that the share of new cars purchased on credit slid from 70% to 33% between 2021 and 2022. Others noted that consumers are downtrading from steak to chicken and sausage.

Even signs of optimism were tempered. For example, an e-commerce leader said that, although cyclical factors won’t derail longer-term investment initiatives, they have deployed capital conservatively in 2023 and tended to concentrate on the highest quality customers when doing so.

Righting the fiscal ship

Another objective of my trip was to assess the chances of success of the new fiscal rule put forth by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s administration. The previous iteration – a constitutional amendment – was necessary after years of fiscal mismanagement, which had led to a cycle of inflationary spirals and debt crises. By forcing spending restraint and stabilizing primary budget deficits, the country was able to win hard-fought favor with global investors. Then it stopped working.

We rightly fear “creative” EM politicians when it comes to fiscal matters, and the administration of Jair Bolsonaro proved especially creative in sidestepping fiscal constraints. This only aggravated the country’s deteriorating fiscal condition owed to mismanagement in the previous decade. The upshot was a reversal in the multi-year decline of the SELIC1 benchmark rate, which in turn increased risk premia across all Brazilian assets.

We were concerned that a second Lula administration would be more ideological and seek to dilute the new fiscal framework. Countering that, however, are institutions that are stronger than what Lula encountered in his first term: The central bank is now independent, and the fragmented congress has greater center-right representation.

Economic assumptions underpinning new fiscal rule

Should revenue growth fall short of the government’s rosy projections, the country would potentially face budget shortfalls or see the need for growth-sapping tax increases to fill the gap.

Source: Janus Henderson Investors.

We believe Lula’s administration based its initial proposal on overly optimistic GDP and interest rate assumptions. Had a pliant congress passed the initiative outright, we’d have expected to see a fierce market reaction. Instead, since last month’s passage, the country’s benchmark stock index is only down roughly 5.0% and the 10-year sovereign yield has rallied. On the surface, this indicates the market’s acceptance of the final framework, despite what many say is an overreliance on revenue increases to maintain budget stability. To be determined is whether the focus on spending is grounded in realistic economic assumptions or higher taxes will be needed to fill the gap.

One part of the equation

Whether Brazil ultimately proves successful in trimming its budget deficit matters to equity investors. We believe investment outcomes tend to improve when one focuses on countries with reformist governments that recognize the importance of a thriving private sector and maintain fiscal discipline. Brazil does have a rich history of innovative companies servicing a large and upwardly mobile population. By recapturing the fiscal discipline that had previously broken the cycle of jumping from crisis to crisis, Brazil’s government can ensure a landscape that allows its companies to thrive, thus making them even more attractive components within an EM equities allocation.

1The SELIC interest rate is the Central Bank of Brazil’s main tool for implementing monetary policy within the country.

Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point. 1 bp = 0.01%, 100 bps = 1%.

Monetary Policy refers to the policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. It includes controlling interest rates and the supply of money.

Quantitative Tightening (QT) is a government monetary policy occasionally used to decrease the money supply by either selling government securities or letting them mature and removing them from its cash balances.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- Shares/Units can lose value rapidly, and typically involve higher risks than bonds or money market instruments. The value of your investment may fall as a result.

- Shares of small and mid-size companies can be more volatile than shares of larger companies, and at times it may be difficult to value or to sell shares at desired times and prices, increasing the risk of losses.

- Emerging markets expose the Fund to higher volatility and greater risk of loss than developed markets; they are susceptible to adverse political and economic events, and may be less well regulated with less robust custody and settlement procedures.

- This Fund may have a particularly concentrated portfolio relative to its investment universe or other funds in its sector. An adverse event impacting even a small number of holdings could create significant volatility or losses for the Fund.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- If the Fund holds assets in currencies other than the base currency of the Fund, or you invest in a share/unit class of a different currency to the Fund (unless hedged, i.e. mitigated by taking an offsetting position in a related security), the value of your investment may be impacted by changes in exchange rates.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- The Fund may incur a higher level of transaction costs as a result of investing in less actively traded or less developed markets compared to a fund that invests in more active/developed markets.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.

Specific risks

- Shares/Units can lose value rapidly, and typically involve higher risks than bonds or money market instruments. The value of your investment may fall as a result.

- Shares of small and mid-size companies can be more volatile than shares of larger companies, and at times it may be difficult to value or to sell shares at desired times and prices, increasing the risk of losses.

- Emerging markets expose the Fund to higher volatility and greater risk of loss than developed markets; they are susceptible to adverse political and economic events, and may be less well regulated with less robust custody and settlement procedures.

- The Fund may invest in China A shares via a Stock Connect programme. This may introduce additional risks including operational, regulatory, liquidity and settlement risks.

- If a Fund has a high exposure to a particular country or geographical region it carries a higher level of risk than a Fund which is more broadly diversified.

- This Fund may have a particularly concentrated portfolio relative to its investment universe or other funds in its sector. An adverse event impacting even a small number of holdings could create significant volatility or losses for the Fund.

- The Fund may use derivatives with the aim of reducing risk or managing the portfolio more efficiently. However this introduces other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- If the Fund holds assets in currencies other than the base currency of the Fund, or you invest in a share/unit class of a different currency to the Fund (unless hedged, i.e. mitigated by taking an offsetting position in a related security), the value of your investment may be impacted by changes in exchange rates.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.