Rate cuts in the developed world kicked off meaningfully in June 2024 with the Bank of Canada, then the European Central Bank (ECB). The Bank of England followed in August 2024 and the US Federal Reserve played catch up in September 2024 with a 50 basis points (bp) first cut. There have been cumulative ‘soft-landing’ rate cuts of between 100bp and 225bp across the developed world, yet over this same time period we have witnessed a sustained rise in long-dated bond yields.1 This has culminated in current post-Covid yield highs for 30-year bonds in a number of countries, with some markets such as the UK trading at levels not seen for over 25 years.

Recall that bond prices fall when yields rise and vice versa, so recent movements in longer-dated bond yields have led to underperformance (and in most cases negative returns) from this area of the bond market. Movements have varied across bond maturities and countries, so careful selection has been crucial.

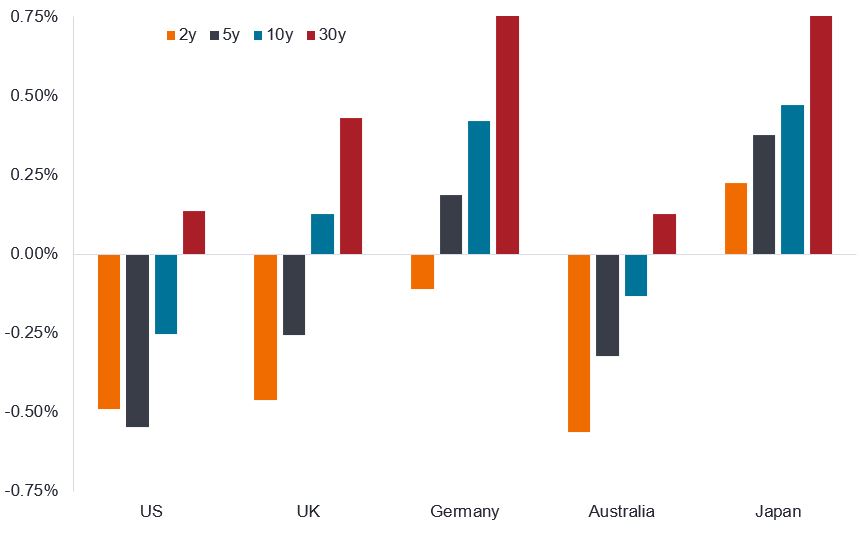

Country and curve positioning matters

Yield change (year to date) for government bonds of different maturities

Source: Bloomberg, 2-year, 5-year, 10-year and 30-year government bonds for selected countries, change in yield (percentage point change year to date), 31 December 2024 to 15 August 2025. Y = year. Past performance does not predict future returns.

At times in 2025 we have witnessed bouts of rising yields which have felt crisis-like: the UK in early January 2025, and Japan’s long end in May 2025. However, for the most part, the rise in long-end bond yields has been persistent but less headline-grabbing. In August, we have seen new highs for this cycle in 30-year Gilts and 30-year European bonds. The US bond market has outperformed on rising expectations of rate cuts and 30-year yields still hover just 20bp below the highs from October 2023.2 There remain medium term concerns about inflation and fiscal deficits that continue to bubble up in different countries at different times: for example, in August 2024 it was the persistence of UK inflation, in March 2025 German fiscal expansion. Importantly however, there does appear to be what might be described as a “market structure” issue: a structural slowdown in duration demand (i.e. demand for longer-dated bonds) which is causing sustained and continued pressure on long-dated bond yields in a number of geographies. There remains a sobering fragility to this part of global bond markets which is noteworthy.

So what is going on?

As central banks cut interest rates in an easing cycle, some steepening of the yield curve is to be expected. However, beyond this cyclical driver, there are three factors that appear to account for the rise in long-end yields:

- Buyers strike: The traditional buyers of 30 year plus bonds come from the institutional investment community. In different countries there has been reduced demand from these investors for their own particular domestic reasons: in the UK the collapse of duration demand from the defined benefit pension funds post 2022; in Europe it is pension fund reform in the Netherlands which has been a focal point; and in Japan a structural reduction in demand from the life insurance sector (reduced inflows to life insurers versus banks and life insurance sales shifting away from super-long liability products).

- Quantitative Tightening: At the same time as cutting rates, central banks have continued to shrink their holdings of government bonds. Except for the UK, where active selling of bonds has been part of the policy mix since November 2022 and has included selling longer dated bonds back to the market, quantitative tightening has been in ‘passive’ form i.e. letting existing holdings mature and not be reinvested. The Bank of England are widely expected to announce a reduction in the pace of the active selling in September 2025: the debate is by how much.

- Fiscal deficit concerns: There is no end in sight to the growth of deficits. The German election in February saw a dramatic increase in debt-fuelled infrastructure and military spending announced, whilst Japan and Canada await post-election fiscal plans which are likely to see increased spending. The UK and France continue to struggle to exhibit credible fiscal discipline whilst the recent US “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” was somewhat fiscally expansionary (albeit less so after the effects of tariff income).

We are now in an environment across the developed world of non-synchronised interest rate cycles, which is being reflected in the increasingly divergent performance of bond markets across different countries in the developed world. Selecting the right geography to have duration and the right part of the yield curve is of paramount importance.

1Source: LSEG Datastream, reference is to cumulative rate cuts among US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of Canada and Bank of England, 31 May 2024 to 31 July 2025.

2Source: Bloomberg, US 30-year government bond yield,19 October 2023 to 19 August 2025. Yields may vary over time and are not guaranteed.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

Basis points: Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point, 1bp = 0.01%.

Duration: Duration measures the sensitivity of a bond’s or fixed-income portfolio’s price to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates, and vice versa.

Federal Reserve (Fed): The central bank of the US that determines its monetary policy.

Fiscal/Fiscal policy: Describes government policy relating to setting tax rates and spending levels. Fiscal deficit represents the gap between government revenues and spending. A deficit implies that state sector spending exceeds the revenues collected in a given year.

Issuance: The act of making bonds available to investors by the borrowing (issuing) company, typically through a sale of bonds to the public or financial institutions.

Maturity: The maturity date of a bond is when the principal investment (and any final income payment) is paid to investors. Shorter-dated bonds generally mature within five years, medium-term bonds within five to 10 years, and longer-dated bonds after 10+ years.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. Monetary policy tools include setting interest rates and controlling the supply of money.

Quantitative tightening: A monetary policy tool used by central banks to decrease the money supply by either selling government securities, or letting then mature and removing them from its cash balances.

Soft landing: A situation where central bank curbs inflation by slowing an economy without triggering a recession.

Tariff: A tax or duty paid on imports of goods.

Total return: The combined return from income and any change in capital value of an investment.

Yield: The level of income on a security over a set period, typically expressed as a percentage rate.

Yield curve:A graph that plots the yields of government bonds against their maturities. Normally, the yield curve is upward sloping, where yields for shorter-maturity bonds are lower than yields for bonds with a longer maturity.

Volatility measures risk using the dispersion of returns for a given investment. The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index moves up and down.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- The Fund invests in high yield (non-investment grade) bonds and while these generally offer higher rates of interest than investment grade bonds, they are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- If a Fund has a high exposure to a particular country or geographical region it carries a higher level of risk than a Fund which is more broadly diversified.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different bonds will be affected differently. In particular, bond prices generally fall when interest rates rise or are expected to rise. This is especially true for bonds with a higher sensitivity to interest rate changes. A material portion of the fund may be invested in such bonds (or bond derivatives), so rising interest rates may have a negative impact on fund returns.

Specific risks

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall. High yielding (non-investment grade) bonds are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- Emerging markets expose the Fund to higher volatility and greater risk of loss than developed markets; they are susceptible to adverse political and economic events, and may be less well regulated with less robust custody and settlement procedures.

- The Fund may invest in onshore bonds via Bond Connect. This may introduce additional risks including operational, regulatory, liquidity and settlement risks.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- If the Fund holds assets in currencies other than the base currency of the Fund, or you invest in a share/unit class of a different currency to the Fund (unless hedged, i.e. mitigated by taking an offsetting position in a related security), the value of your investment may be impacted by changes in exchange rates.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.