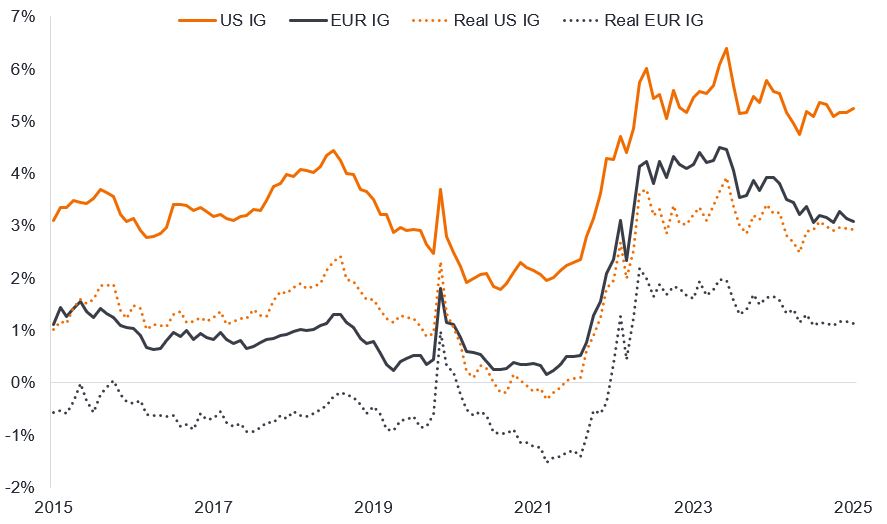

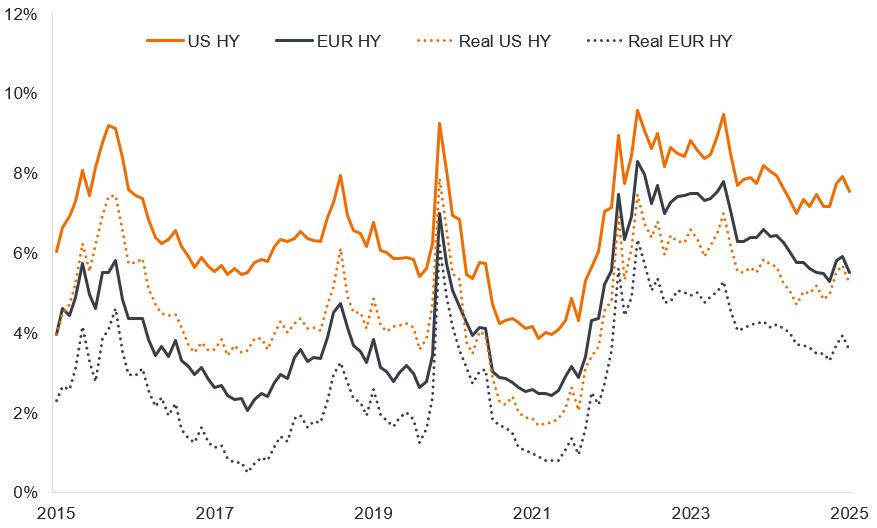

Corporate bonds, in our view, continue to be an attractive proposition for investors. Over the last two years they have comfortably delivered a positive real yield (yield above inflation) in both investment grade (IG) corporate bonds (Figure 1a) and high yield (HY) corporate bonds (Figure 1b).

Figure 1a: Investment grade nominal yields and real yields

Source: Bloomberg: US IG nominal yield = ICE BofA US Corporate Index, yield to worst; EUR IG nominal yield = ICE BofA Euro Corporate Index. 31 May 2015 to 31 May 2025. The yield to worst is the lowest yield a bond with a special feature (such as a call option) can achieve provided the issuer does not default. When used to describe an index, this statistic represents the weighted average across all the underlying bonds held. Real yields are difference of index yield to worst and 5y5y breakevens. 5y5y breakeven inflation is a measure of market-expected inflation over a five year period, starting five years from the current date. It provides a smoothed measure of inflation. Yields may vary over time and are not guaranteed.

Figure 1b: High yield nominal yields and real yields

Source: Bloomberg: US HY nominal yield = ICE BofA US High Yield Index, yield to worst; EUR HY nominal yield = ICE BofA Euro High Yield Index. 31 May 2015 to 31 May 2025. Real yields are difference of index yield to worst and 5y5y breakevens. Yields may vary over time and are not guaranteed.

Many investors are drawn to corporate bonds because of the yield they offer. In accepting greater risk to capital, investors can gain access to yields above money market rates and those offered by developed market government bonds. We see this appeal continuing, particularly as the path for interest rates among leading central banks looks to be skewed to the downside.

Strong fundamentals

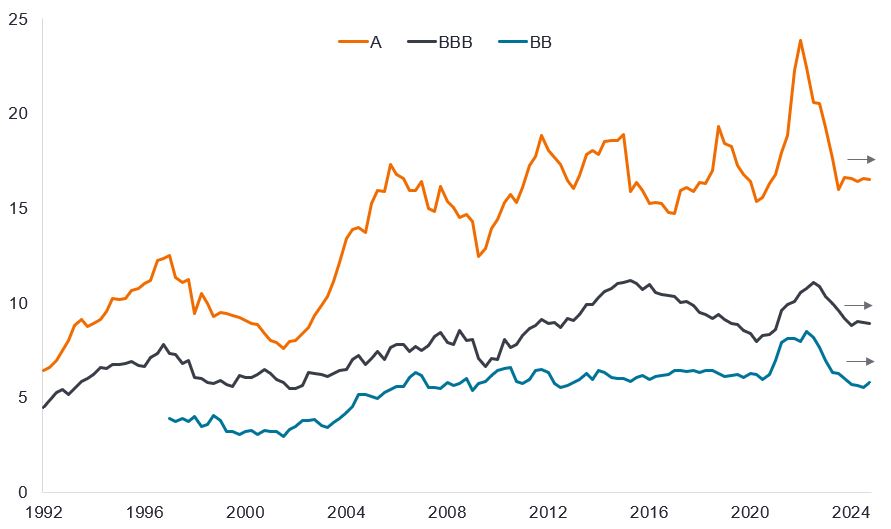

Of course, the yield on corporate bonds counts for little unless it is paid. Happily, defaults remain low and companies outside the lower credit ratings have, for the most part, managed to adapt to higher interest rates. Interest coverage (IC) ratios – which reflect earnings divided by annual interest payments – did fall initially as coupon interest rates reset higher during refinancing. This has begun to stabilise as central bank policy interest rates come down from peak levels and earnings have remained solid. Even at lower levels, current US corporate bond IC ratios are above average historically, emblematic of a generally better quality credit universe.

Figure 2: US interest coverage ratios have stabilised across credit ratings

EBITDA divided by annual interest expense

Source: Bloomberg, S&P Capital IQ, Morgan Stanley Research, 31 March 1992 to 31 December 2024. EBITDA = Earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation. A higher IC ratio indicates a company is better able to meet debt repayments. Past performance does not predict future returns.

Up in quality preference

While many cohorts of credit have recovered since the Liberation Day shock (when President Trump announced sweeping tariffs) spreads on the US CCC-rated group remain notably wider at end May 2025 than they began 2025. These lower-rated high yield bonds tend to be more cyclical with higher debt levels. They are therefore more exposed to both a slowdown in the economy and interest rates lingering at higher levels.

In contrast, investment grade markets and BB rated high yield (BB is the higher quality end of the high yield spectrum) have broadly been on a round trip. Spreads (the additional yield a corporate bond pays over a government bond of similar maturity) initially widened (rose) on growth and inflation fears before narrowing (reducing) once the prospect for tariff de-escalation took hold. Current spread levels are quite tight, however, and are not pricing in any recession. For now, that assessment seems reasonable, as economic data is holding up. While still early days, consumers have not really changed their spending habits and companies appear reluctant to reduce headcount and potentially surrender market share to competitors when the outlook is still uncertain.

There are also geographical differences. With Germany embarking on a path of higher government outlay on infrastructure and Europe as a whole spending more on defence and encouraging reshoring (more localised manufacturing), new revenue opportunities are opening up for companies. Similar to China, we would expect Europe to pursue supportive action to mitigate the more punitive tariffs. By favouring higher quality companies, we think investors can maintain exposure to attractive yields without taking on too much credit risk.

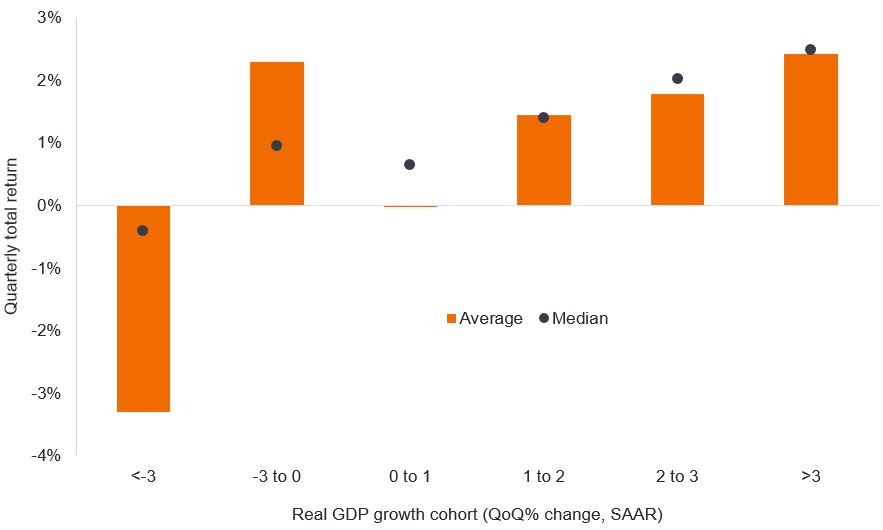

Can high yield tolerate lower growth?

Regardless of the final outcome on tariffs, they are expected to raise costs and policy uncertainty is likely to weigh on confidence. Most economists have lowered their expectations for economic growth in the US. Back in March, the US Federal Reserve (Fed) revised down its forecast for US real gross domestic product (GDP) growth in 2025 to 1.7%, down from a forecast of 2.1 % back in December. It may lower it further at the Fed’s June meeting. High yield bonds typically prefer stronger growth since it often equates to higher earnings, stronger cash flow and, importantly, an amenable environment for issuing bonds as there is typically appetite from investors to take on credit risk. If we look back over the past four decades, on average (whether a mean or median) US high yield bonds have typically returned 1.4% in a quarter where GDP grew between 1%-2% annualised. Over a full year that would be approximately a 5.7% total return from high yield.

Figure 3: US high yield total return

Quarterly total return vs Quarterly real GDP cohorts

Source: Bloomberg, US real GDP, quarter on quarter percentage change, seasonally-adjusted annualised rate (SAAR), ICE BofA US High Yield Index, total return in US dollars each quarter, 30 September 1986 to 31 March 2025. Past performance does not predict future returns.

The differences in the chart between the average (mean) figures and median figures bear explanation. Being the middle figure of a set of numbers, the median strips out extremes to show the central observation. The average (mean) figure captures extremes. So, in quarters where there are sharp drops in GDP (<-3%), the mean figure of -3.3% for high yield returns reflects quarters in 2008 (Global Financial Crisis) and 2020 (COVID) when high yield bond prices fell sharply. Interestingly, shallower GDP falls equate to a positive return from high yield bonds at a mean level because this cohort captures quarters such as Q2 2009 where markets (correctly) took a reduction in the severity of economic decline to signal the worst was over. Bond prices rebounded in anticipation that the downturn was coming to an end.

Figure 3 shows that bond yields can respond noisily to changes in the economic outlook. Stronger corporate fundamentals, however, mean they may be less sensitive than in the past. Yield hungry investors are also likely to provide support to corporate bonds (at least among the higher credit ratings).

Taken together, we remain constructive on credit. A meaningful de-escalation in tariffs would likely see credit spreads tighten. On the other hand, they are already at fairly tight levels, so would be vulnerable to widening if sentiment shifted on bad news. We see advantages in remaining nimble by leaning towards higher quality companies that continue to offer exposure to attractive yields but offer less risk in any sell-off. Whatever the market environment, there are always pricing inefficiencies, but we think there may be better opportunities ahead to add to CCC rated bonds.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

High-yield or “junk” bonds involve a greater risk of default and price volatility and can experience sudden and sharp price swings.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue or forecasts will be realised.

ICE BofA Euro Corporate Index tracks the performance of EUR denominated investment grade corporate debt publicly issued in the Eurobond or Euro member domestic markets.

ICE BofA Euro High Yield Index tracks the performance of EUR denominated below investment grade corporate debt publicly issued in the euro domestic or Eurobond markets.

ICE BofA US Corporate Index tracks the performance of US dollar denominated investment grade corporate debt publicly issued in the US domestic market.

ICE BofA US High Yield Index tracks the performance of US dollar denominated below investment grade corporate debt publicly issued in the US domestic market.

Corporate bond: A bond issued by a company. Bonds offer a return to investors in the form of periodic payments and the eventual return of the original money invested at issue on the maturity date.

Corporate fundamentals are the underlying factors that contribute to the price of an investment. For a company, this can include the level of debt (leverage) in the company, its ability to generate cash and its ability to service that debt.

Coupon: A regular interest payment that is paid on a bond, described as a percentage of the face value of an investment. For example, if a bond has a face value of $100 and a 5% annual coupon, the bond will pay $5 a year in interest.

Credit rating: A score given by a credit rating agency such as S&P Global Ratings, Moody’s and Fitch on the creditworthiness of a borrower. For example, S&P ranks investment grade bonds from the highest AAA down to BBB and high yields bonds from BB through B down to CCC in terms of declining quality and greater risk, i.e. CCC rated borrowers carry a greater risk of default.

Credit spread. The difference in yield between securities with similar maturity but different credit quality. Widening spreads generally indicate deteriorating creditworthiness of corporate borrowers, and narrowing indicate improving.

Default: The failure of a debtor (such as a bond issuer) to pay interest or to return an original amount loaned when due.

Duration: A measure of the sensitivity of a bond’s price to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates and vice versa. Bond prices rise when their yields fall and vice versa.

Federal Reserve (Fed): The central bank of the US which determines its monetary policy.

High yield bond: Also known as a sub-investment grade bond, or ‘junk’ bond. These bonds usually carry a higher risk of the issuer defaulting on their payments, so they are typically issued with a higher interest rate (coupon) to compensate for the additional risk.

Inflation: The rate at which prices of goods and services are rising in the economy.

Investment grade bond: A bond typically issued by governments or companies perceived to have a relatively low risk of defaulting on their payments, reflected in the higher rating given to them by credit ratings agencies.

Interest coverage ratio: A ratio that measures the ability of a company to meet the interest payments on its debt. It is calculated by dividing annual earnings (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) by annual interest expense. The higher the figure the more easily a company can meet repayments.

Maturity: The maturity date of a bond is the date when the principal investment (and any final coupon) is paid to investors. Shorter-dated bonds generally mature within 5 years, medium-term bonds within 5 to 10 years, and longer-dated bonds after 10+ years.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. Monetary policy tools include setting interest rates and controlling the supply of money.

Tariff: A tax or duty imposed by the government of one country on the import of goods from another country.

Total return: The combined return from income and any change in capital value of an investment.

Yield: The level of income on a security over a set period, typically expressed as a percentage rate. For a bond, at its most simple, this is calculated as the coupon payment divided by the current bond price.

Yield to worst: The lowest yield a bond (index) can achieve provided the issuer(s) does not default; it takes into account special features such as call options (that give issuers the right to call back, or redeem, a bond at a specified date).

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- The Fund invests in high yield (non-investment grade) bonds and while these generally offer higher rates of interest than investment grade bonds, they are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- If a Fund has a high exposure to a particular country or geographical region it carries a higher level of risk than a Fund which is more broadly diversified.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- If the Fund holds assets in currencies other than the base currency of the Fund, or you invest in a share/unit class of a different currency to the Fund (unless hedged, i.e. mitigated by taking an offsetting position in a related security), the value of your investment may be impacted by changes in exchange rates.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.

Specific risks

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- The Fund invests in high yield (non-investment grade) bonds and while these generally offer higher rates of interest than investment grade bonds, they are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- Emerging markets expose the Fund to higher volatility and greater risk of loss than developed markets; they are susceptible to adverse political and economic events, and may be less well regulated with less robust custody and settlement procedures.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- The Fund may incur a higher level of transaction costs as a result of investing in less actively traded or less developed markets compared to a fund that invests in more active/developed markets.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.

- In addition to income, this share class may distribute realised and unrealised capital gains and original capital invested. Fees, charges and expenses are also deducted from capital. Both factors may result in capital erosion and reduced potential for capital growth. Investors should also note that distributions of this nature may be treated (and taxable) as income depending on local tax legislation.

Specific risks

- An issuer of a bond (or money market instrument) may become unable or unwilling to pay interest or repay capital to the Fund. If this happens or the market perceives this may happen, the value of the bond will fall.

- When interest rates rise (or fall), the prices of different securities will be affected differently. In particular, bond values generally fall when interest rates rise (or are expected to rise). This risk is typically greater the longer the maturity of a bond investment.

- The Fund invests in high yield (non-investment grade) bonds and while these generally offer higher rates of interest than investment grade bonds, they are more speculative and more sensitive to adverse changes in market conditions.

- Some bonds (callable bonds) allow their issuers the right to repay capital early or to extend the maturity. Issuers may exercise these rights when favourable to them and as a result the value of the Fund may be impacted.

- If a Fund has a high exposure to a particular country or geographical region it carries a higher level of risk than a Fund which is more broadly diversified.

- The Fund may use derivatives to help achieve its investment objective. This can result in leverage (higher levels of debt), which can magnify an investment outcome. Gains or losses to the Fund may therefore be greater than the cost of the derivative. Derivatives also introduce other risks, in particular, that a derivative counterparty may not meet its contractual obligations.

- If the Fund holds assets in currencies other than the base currency of the Fund, or you invest in a share/unit class of a different currency to the Fund (unless hedged, i.e. mitigated by taking an offsetting position in a related security), the value of your investment may be impacted by changes in exchange rates.

- When the Fund, or a share/unit class, seeks to mitigate exchange rate movements of a currency relative to the base currency (hedge), the hedging strategy itself may positively or negatively impact the value of the Fund due to differences in short-term interest rates between the currencies.

- Securities within the Fund could become hard to value or to sell at a desired time and price, especially in extreme market conditions when asset prices may be falling, increasing the risk of investment losses.

- Some or all of the ongoing charges may be taken from capital, which may erode capital or reduce potential for capital growth.

- CoCos can fall sharply in value if the financial strength of an issuer weakens and a predetermined trigger event causes the bonds to be converted into shares/units of the issuer or to be partly or wholly written off.

- The Fund could lose money if a counterparty with which the Fund trades becomes unwilling or unable to meet its obligations, or as a result of failure or delay in operational processes or the failure of a third party provider.