Traditionally, many investors have relied on the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (U.S. Agg) as a proxy for their core bond allocation.

But sticking too closely to the U.S. Agg has historically proven to be suboptimal from a risk-return perspective. That’s why we believe investors should consider a multisector income fund for their core bond allocation.

The number one reason to consider a multisector fund for a core bond allocation is that multisector funds have historically generated better risk-adjusted and absolute returns than the U.S. Agg, core, and core-plus categories.1

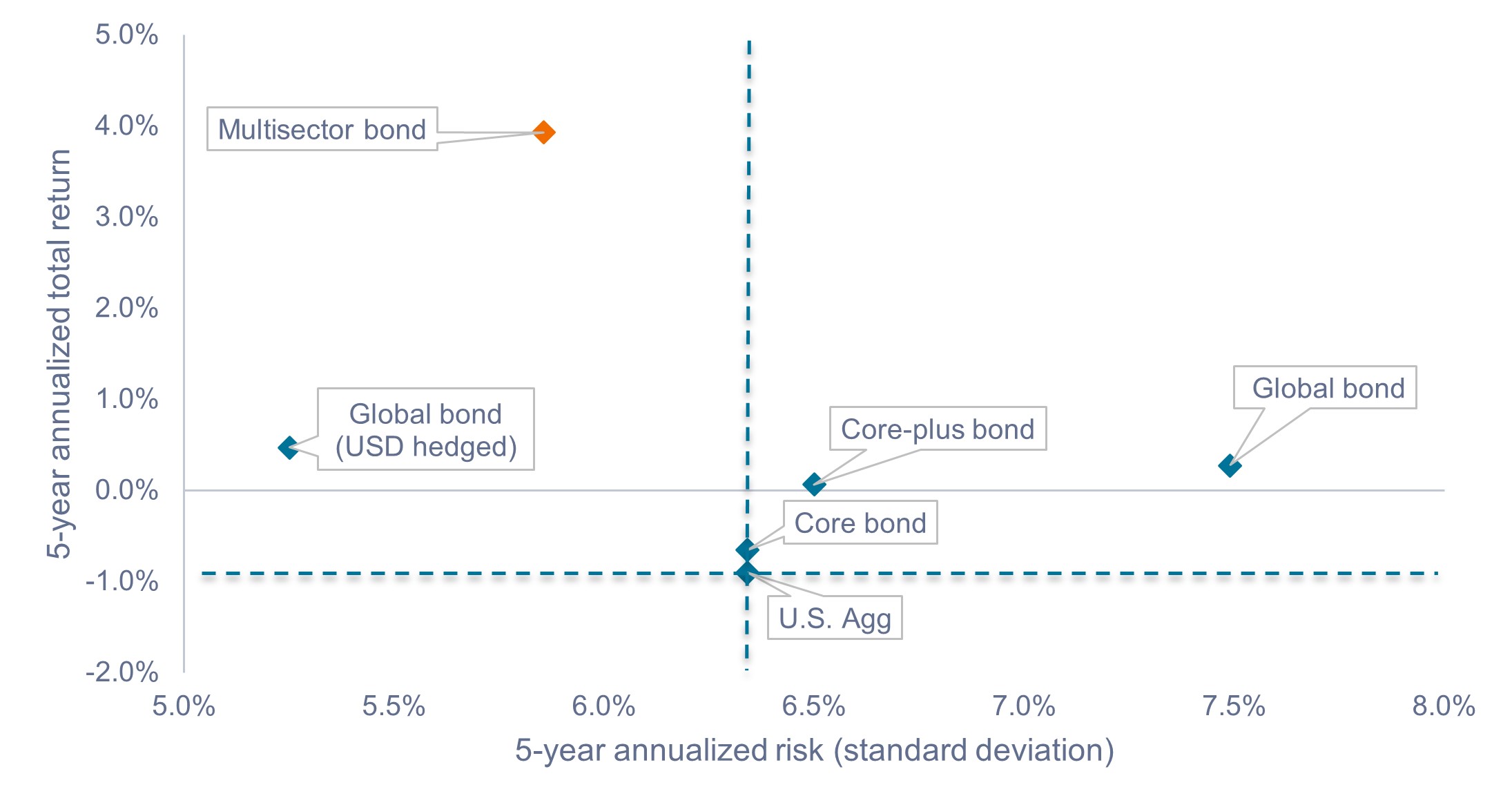

As shown in Exhibit 1, over the past five years, the multisector category has provided higher returns with lower volatility than the U.S. Agg, as well as the global bond, core bond, and core-plus categories.2

Exhibit 1: Total returns and risk (May 2020 – May 2025)

Multisector funds have recently been rewarded for their mix of interest-rate and credit-spread risk.

Source: Morningstar, as of 31 May 2025. Past performance does not predict future results. Bond categories as per Morningstar and defined in the Definitions and Disclosures section.

This record of strong risk-adjusted performance may come as a bit of a surprise to investors, many of whom think of multisector funds as being “higher risk” than core and core-plus funds.

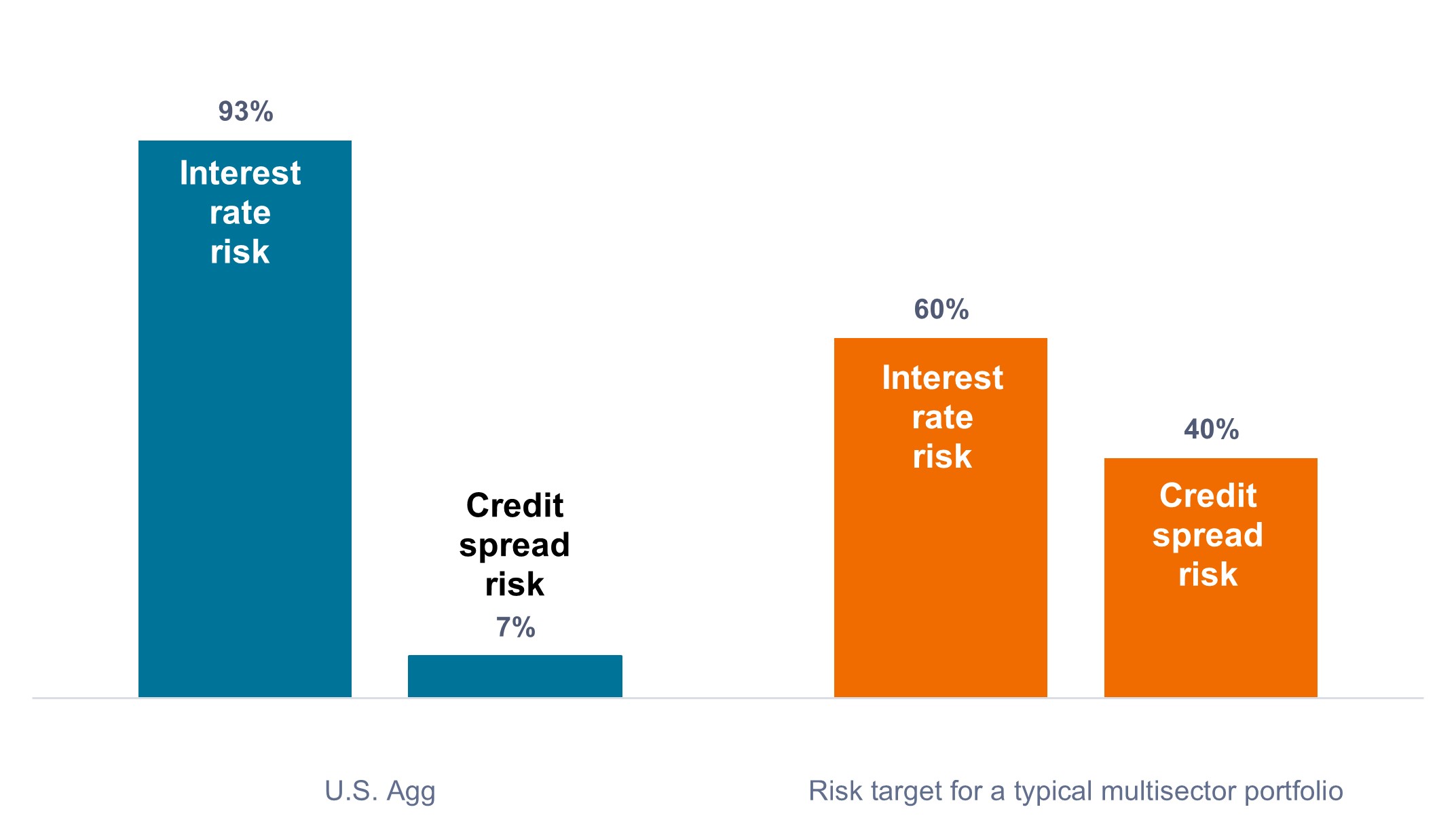

While it is true that over the long term multisector funds exhibit a higher level of volatility than core and core-plus categories, we think the more important takeaway is that the primary objective of multisector funds may not necessarily be to target a higher level of risk, but rather to target a more efficient mix of interest-rate and credit-spread risk.

As shown in Exhibit 2, the multisector category may have more flexibility to balance these risks under varying market conditions as it seeks to maximize the long-term return potential from fixed income securities.

Exhibit 2: Risk factor decomposition (March 2020 – March 2025)

Multi-sector portfolios aim to provide a more balanced mix of risk factors.

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, as of 31 March 2025.

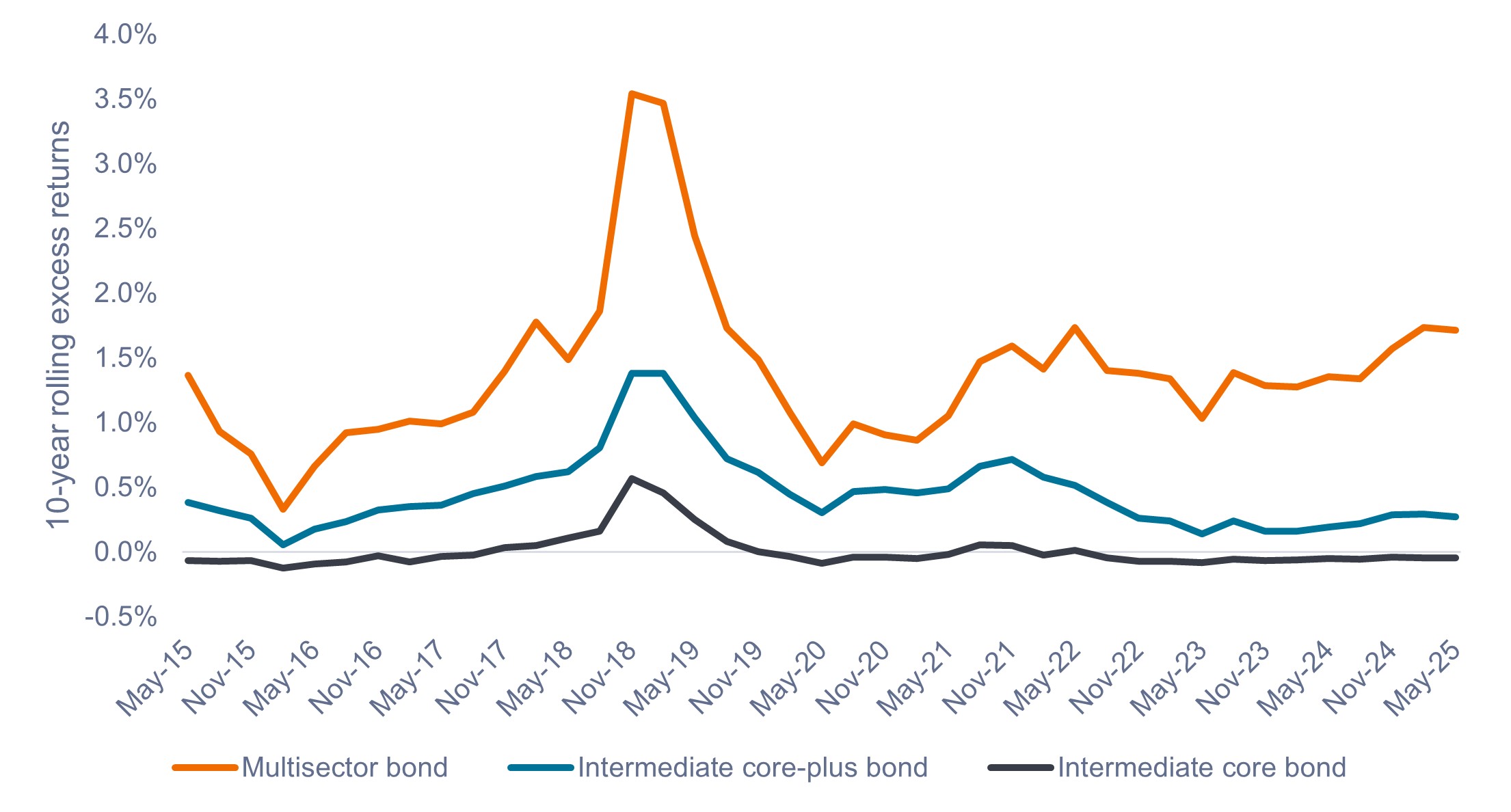

The present trend of multisector funds outperforming core and core-plus strategies is not only a recent phenomenon. The multisector category has outperformed the core and core-plus categories on an excess return basis for all 10-year rolling periods over the past 10 years, as shown in Exhibit 3.

Furthermore, over a 20-year period the multisector category has shown an ability to outperform the bellwether core-plus category through numerous economic, market, and policy cycles by a statistically meaningful 1.07% annualized.

In our view, the outperformance speaks to the benefit of having diversified income streams and a better balance of credit-spread and interest-rate risk.

Exhibit 3: 10-year rolling excess returns (May 2015 – May 2025)

Even through downturns, multisector funds have outperformed over the long term.

Source: Morningstar, as of 31 May 2025. Past performance does not predict future results.

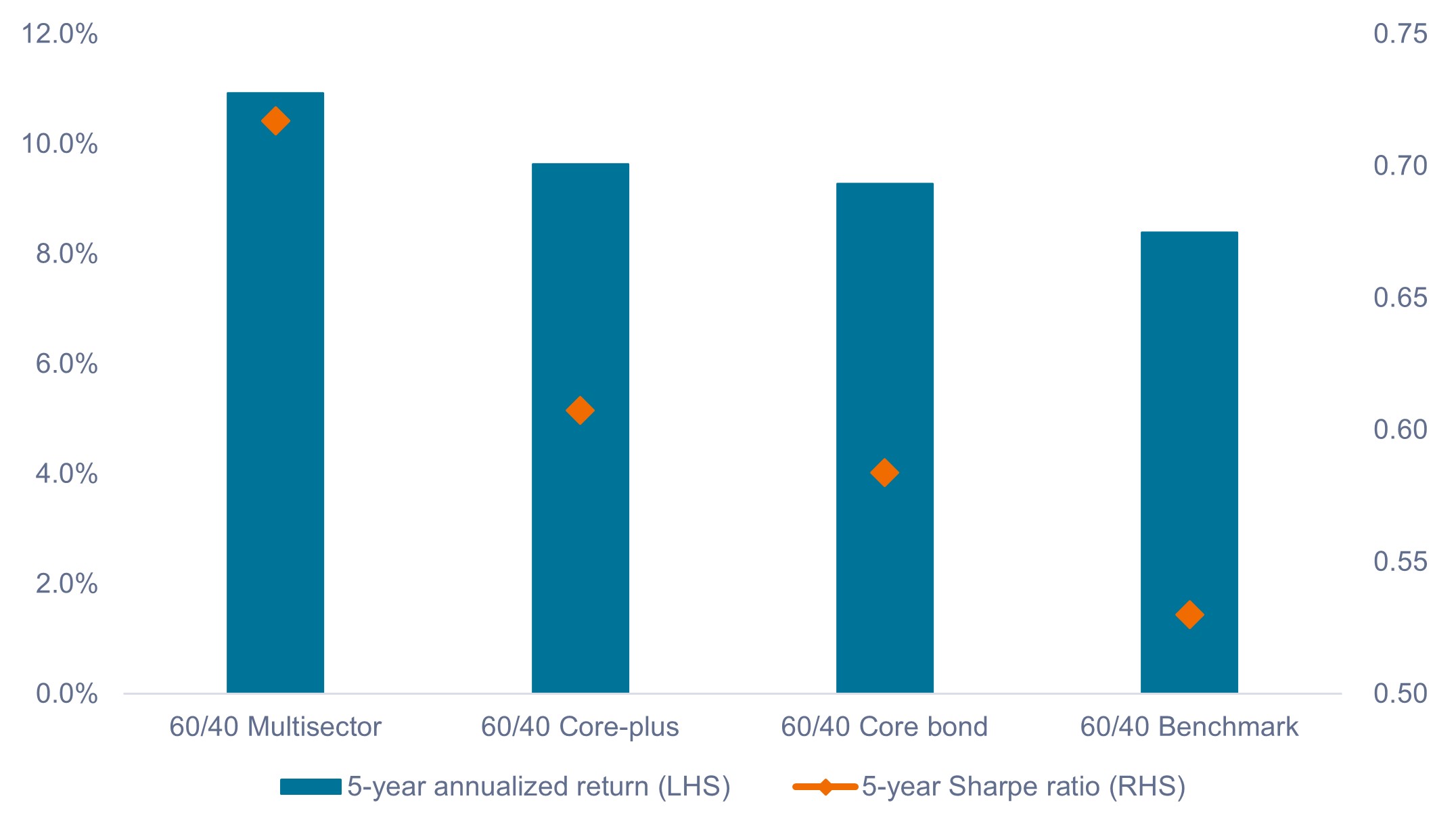

Some investors may be concerned that increasing risk within their fixed income allocation could reduce their bond allocation’s effectiveness in providing a ballast against equity volatility.

But we find that, within the confines of a 60/40 portfolio, using a multisector fund as a core bond allocation has resulted in marginal increases in volatility, while boosting total returns and Sharpe ratios, as shown in Exhibit 4.

Therefore, taking on a slightly higher and more even mix of risk within one’s bond allocation may be a more efficient way of building a balanced portfolio.

Exhibit 4: Balanced portfolio (60/40) total returns and Sharpe ratios (May 2020 – May 2025)

The risk-return characteristics of multisector funds have been additive within balanced portfolios.

Source: Morningstar, as of 31 May 2025. Past performance does not predict future results.

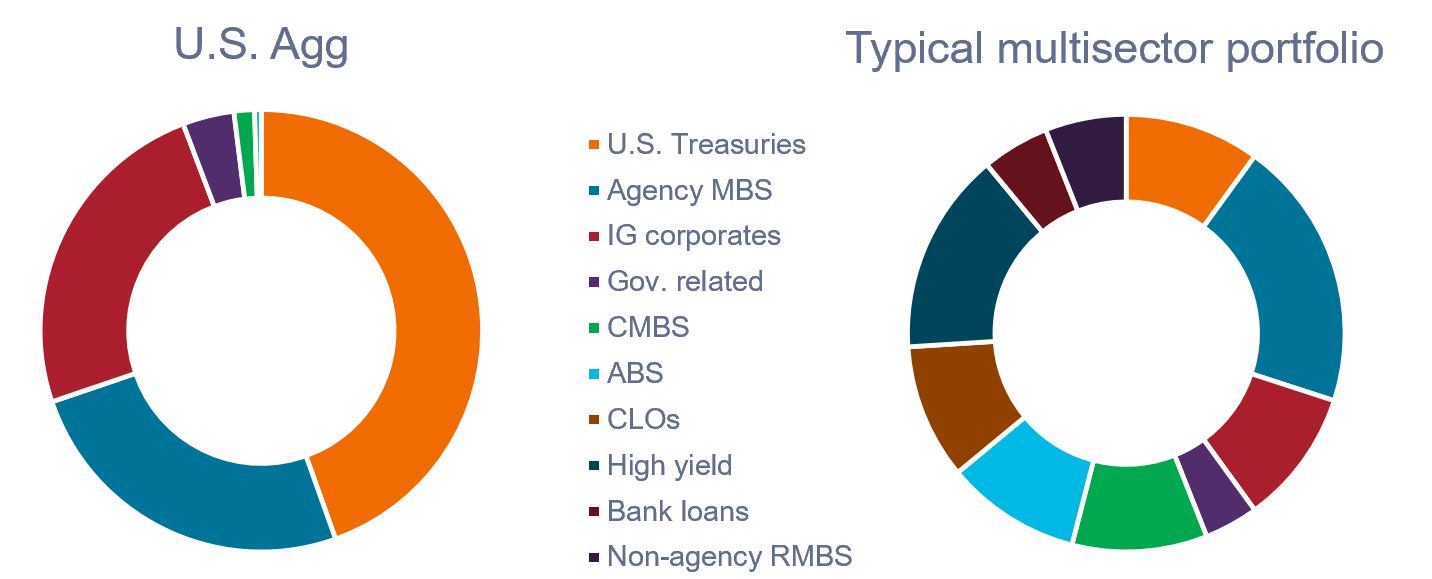

How do multisector funds differ from traditional core and core-plus funds? The primary distinction is that multisector portfolios typically offer exposure to a wider selection of fixed income sectors.

As shown in Exhibit 5, the U.S. Agg is overwhelmingly weighted in U.S. Treasuries (currently 45%), agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS), and investment-grade (IG) corporates. In contrast, typical multi-sector portfolios aim to provide exposure to a broad array of fixed income sectors, offering better diversification of risk exposures, borrowers, and sources of yield.

Exhibit 5: Sector weightings: U.S. Agg vs. a typical multi-sector portfolio

Multi-sector portfolios may provide better access to an array of fixed income opportunities.

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, as of 31 May 2024.

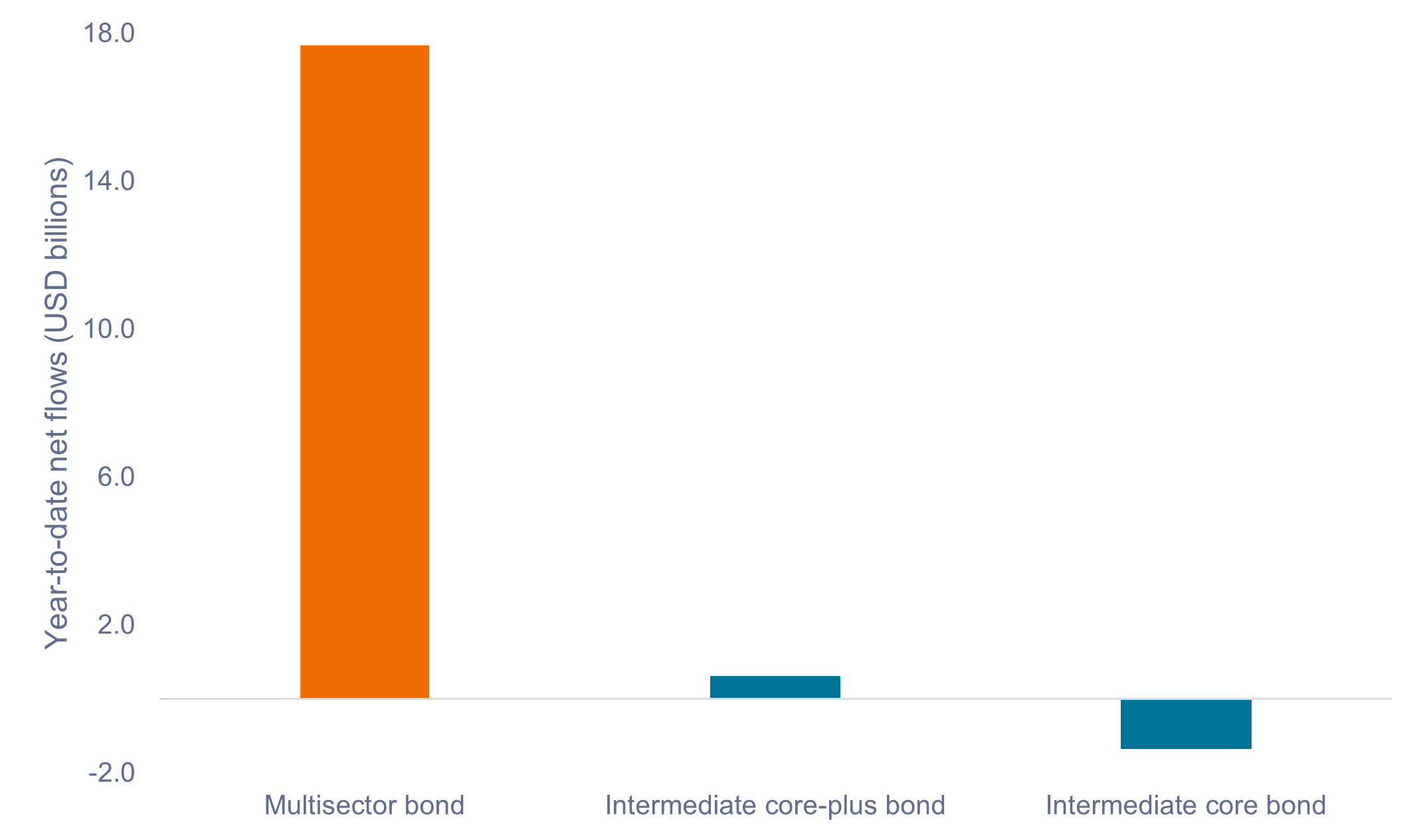

Thus far in 2025, investors have been voting with their dollars, as flows into multisector funds have far surpassed flows into other core and core-plus strategies. We believe this trend may point to multisector funds gaining recognition for their utility in building efficient portfolios suited to long-term investor goals.

Exhibit 6: Year-to-date net flows (Jan 2025 – May 2025)

Capital flows into multisector funds have far surpassed traditional core strategies in 2025.

Source: Morningstar, as of 31 May 2025. Past performance does not predict future results.

In summary

In our view, it is essential for an entire portfolio to contribute to an investor’s long-term investment goals. We believe that, over the long term, multisector income funds may lead to better outcomes through their more diverse exposure and better balance of interest-rate and credit-spread risk.

1 Multisector, core, and core-plus categories are as per Morningstar categories and are defined in the Definitions and Disclosures section. All data in this article relating to Morningstar categories are based on the peer group median.

2 By definition, core and core-plus strategies are constrained by their to the U.S. Aggregate Index.

The Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, often called the “Agg,” is a broad-based, market-weighted index representing the U.S. investment-grade, fixed-rate bond market.

Credit quality ratings are measured on a scale that generally ranges from Aaa (highest) to C (lowest).

Credit spread risk is the risk that changes in the spread between the yield of a corporate bond and a government bond will negatively impact the market value of the corporate bond. It reflects the perceived credit risk of the corporate issuer, as reflected in the difference in yields. A wider spread indicates higher credit risk and a greater yield premium demanded by investors.

Duration measures a bond price’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates and vice versa.

Excess return refers to the difference between an investment’s actual return and the return of a benchmark or risk-free asset. Essentially, it’s the amount by which an investment outperforms a reference point, often a market index or a risk-free rate like a government bond.

Interest rate risk is the risk that the value of a bond or other fixed-income investment will be adversely impacted by a change in interest rates.

Morningstar’s intermediate core bond category describes fixed-income funds that primarily invest in investment-grade U.S. government, corporate, and securitized debt, with a duration between 75% and 125% of the three-year average effective duration of the Morningstar Core Bond Index. These funds generally hold less than 5% in below-investment-grade debt.

Morningstar’s core-plus bond funds invest primarily in investment-grade US fixed-income issues including government, corporate, and securitized debt. However, they generally have greater flexibility than core offerings to hold non-core sectors such as corporate high yield, bank loan, emerging-markets debt, and non-US currency exposures.

Morningstar’s multisector bond category generally takes on more credit risk than portfolios in the intermediate core and core-plus groups. Typically, multisector funds hold between a third and two thirds of their portfolios in bonds with below-investment-grade ratings. As the category name suggests, multisector funds invest across a wide range of bond sectors. These include corporate bonds, sovereign developed- and emerging-markets debt, and securitized credit, with some holding large stakes in nonagency mortgages.

Morningstar global bond funds invest 40% or more of their assets in fixed-income instruments issued outside the United States. These funds can have varying allocations between US and non-US bonds, as well as between high and low-quality bonds.

The Sharpe ratio is a metric used in finance to assess the performance of an investment by adjusting for its risk. It measures the excess return (return above a risk-free rate) per unit of risk (usually measured by standard deviation). A higher Sharpe ratio generally indicates a better risk-adjusted return, meaning the investment is providing more returns for the level of risk taken.

Standard deviation is a statistical measure that quantifies how much an investment’s returns deviate from its average return. Essentially, it tells you how volatile an investment is, meaning how much its price fluctuates over time. A higher standard deviation indicates greater price volatility, and therefore higher risk, while a lower standard deviation suggests more stable returns and lower risk.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Actively managed portfolios may fail to produce the intended results. No investment strategy can ensure a profit or eliminate the risk of loss.

Diversification neither assures a profit nor eliminates the risk of experiencing investment losses.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) may be more sensitive to interest rate changes. They are subject to extension risk, where borrowers extend the duration of their mortgages as interest rates rise, and prepayment risk, where borrowers pay off their mortgages earlier as interest rates fall. These risks may reduce returns.

Securitized products, such as mortgage-backed securities and asset-backed securities, are more sensitive to interest rate changes, have extension and prepayment risk, and are subject to more credit, valuation and liquidity risk than other fixed-income securities.