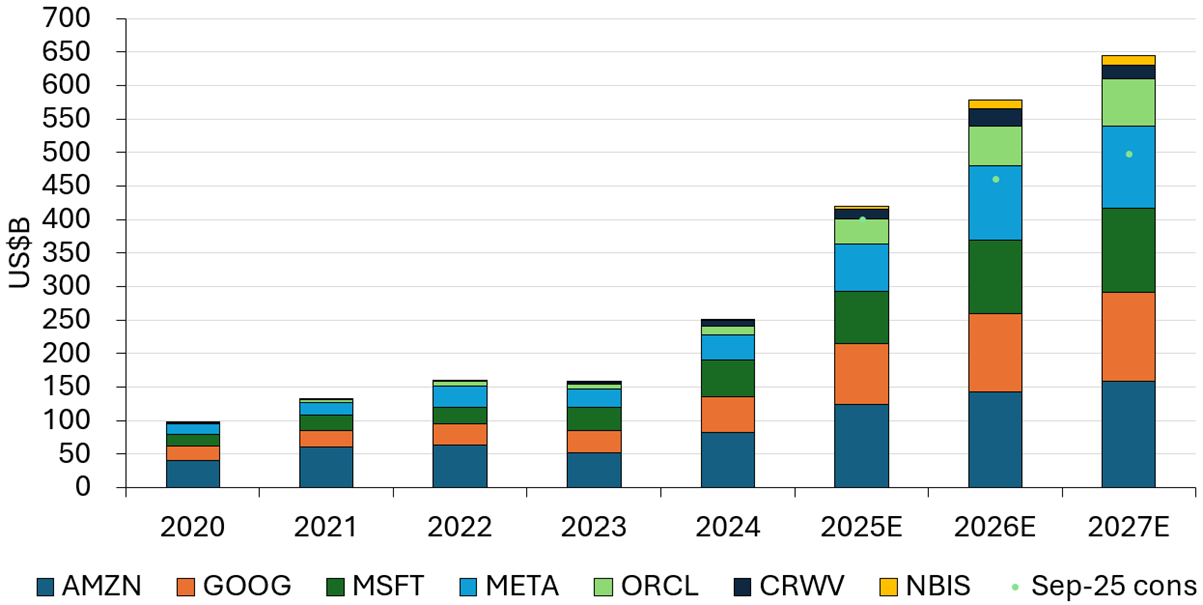

Before we talk about our outlook for the year ahead it is important to review how sustainable equities have fared. Artificial intelligence (AI) dominated stock market returns in 2025. Hyperscalers like Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet and Meta committed over US$400bn to AI infrastructure, with total capital expenditure (capex) expected to reach US$600bn in 2026 (Figure 1). Companies exposed to this tsunami of capital – leading edge semiconductors, memory, networking, electrical equipment, power generation – delivered strong returns, leaving most other sectors languishing (with the exception of banks and defence).

Figure 1: Hyperscaler and neocloud AI capex

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, company reports, Bloomberg (estimates) and Bernstein analysis as at 27 January 2026. There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Physical AI – a new era of industrialisation

The advent of AI represents a major narrative shift. For many years we have talked about digitalisation, electrification and decarbonisation. Digitalisation has been all about reducing the capital intensity of economic growth; driving efficiencies around resource consumption; enabling electrification; promoting clean technologies and reducing carbon emissions. Now digitalisation is becoming resource and energy intensive. It requires massive capital formation with vast energy needs. Digital has suddenly become very physical. We are entering a new era of industrialisation – of physical AI manifested in robotics and intelligent autonomous machines.

The technological visionaries are trying to sell a future where computers and robots take on a lot of work currently done by humans. And unsurprisingly, replacing humans will require vast amounts of resources and energy. Coincident to this we have geopolitical fragmentation with a shift towards regional hegemony. Multilateral co-operation has waned. Tariffs and imperatives around supply chain security and economic resilience are leading to a rupturing of historical trading patterns. This is also contributing to the new era of industrialisation. AI datacentres, the reshoring of production capacity of critical industries, power generation, energy and mining – whichever direction you look, capex is back.

Opportunities remain amid energy transition headwinds

From an environmental perspective, at first glance, there is not much to cheer about. 2025 was one of the three hottest years ever recorded, with the three-year global temperature average breaching the 1.5°C Paris Agreement. There were climate extremes on every continent – scientists tracked 157 extreme weather events including deadly heatwaves, floods and typhoons. Meanwhile, carbon emissions kept on climbing, hitting a record high in 2025, and at same time global climate diplomacy stuttered badly with the UN Climate Change Conference ‘COP 30’ in Brazil failing to deliver a commitment to phase out fossil fuels. Although renewable energy growth is robust it is being outpaced by overall global energy demand growth, with fossil fuels filling the gap.

While the US government has retrenched on its environmental commitments and climate seems to have fallen far down the global agenda, all is not lost. There is still strong policy commitment from other parts of the world, corporates remain committed to decarbonisation and there is continuing momentum in clean technology innovation and investment. On the policy front the EU continues to lead the way, implementing its Green Deal agenda and advancing the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which enters full force in January 2026.

China continues clean tech dominance in 2026

From a corporate perspective, a PwC study in late 2025 found that 84% of large companies were either maintaining or increasing their climate commitments. We can attest to this from our company engagements. China is leading the way in clean tech investment and deployment. Although it is true that China continues to invest in coal power, this is mainly for the purposes of back-up generation and energy security. Importantly, China has been investing hundreds of billions in clean technology industries over the past decade and is achieving dominance in production of solar, batteries and electric vehicles.

Thanks to China, 2025 was a year of record global investment in renewable energy technology – reaching US$2 trillion, which was double the amount invested in fossil fuels. Electric vehicles (EVs) also had a record year of sales in 2025 reaching over 25% of global car sales. While the focus has been on the lack of commitment from the US much of the rest of world has been making steady progress. More than 50% of Chinese car sales are now EVs and Chinese exports are now penetrating other Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries with Vietnam at 40%, Thailand at 20% and Indonesia at 15%. The EU is at 26%, the UK at 33%, and even Turkey is up to 17%; and there is a similar story in many Latin American countries.1

Nature action plans and policy momentum signal reshaping business models

Looking beyond climate and clean tech there were encouraging developments in other environmental and social trends. 2025 was the year that biodiversity entered the mainstream. The new Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) released its final recommendations, prompting many firms to start evaluating their impacts and dependencies on nature. Biodiversity loss became recognised as a material risk – for sectors like agriculture, food and beverage, building materials, and fashion. While supply chain disruptions from ecosystem degradation were identified as threats to business continuity.

Accordingly, 2025 saw the first wave of corporate “nature action” plans: companies set targets on issues like zero-deforestation, regenerative agriculture, and ecosystem restoration to mitigate these risks. Governments, especially in Europe, accelerated “nature-positive” policies. The EU moved toward mandating biodiversity disclosures and planning for Digital Product Passports (by 2026 in industries such as textiles and electronics) to track a product’s materials and environmental footprint across its life cycle. Regulators also introduced or enforced Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes and circular economy laws, pushing companies to design out waste and take responsibility for products at end-of-life. As a result, by the end of 2025 more companies were embedding circular design and nature-based considerations (like sustainable sourcing and habitat protection) into operations.

GLP-1 drugs: A potential game-changer for healthcare and food demand

A major social theme last year was public health and nutrition. There was growing awareness of the links between nutrition, chronic disease, and societal costs. Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) in particular came under scrutiny. These cheap, convenient foods have been implicated in obesity and other health problems, sparking debate about the food industry’s role in long-term societal health. This has coincided with the wider availability of novel weight loss drugs such as GLP-1s, which are being viewed as having potentially revolutionary impacts on public health.

Against this backdrop dietary habits are shifting, and many food and beverage companies have delivered poor investment returns as they race to adapt. Supply chain labour conditions and human rights also stayed in focus. Investors filed resolutions urging companies to improve supply chain transparency and address risks like modern slavery and child labour. Europe’s pending Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), slated for enforcement starting 2026 will require companies to identify and mitigate human rights and environmental risks in their global supply chains. Anticipating this, many multinationals in 2025 began ramping up supply chain audits and engagement with suppliers on social standards.

What is in store for investors as we look ahead to this year?

AI related investment is still in its early stages, and we expect it to remain a dominant theme in 2026. Hyperscaler capex is projected to increase by up to 50% compared to last year with 14 gigawatts (GW) of new datacentre capacity planned.2 We are mindful, however, of physical limitations to the pace of growth. The resources and investment required for even 1 GW datacentre are vast – up to 600 football field worth of land filled with 200,000 tonnes of equipment comprising cables, fibre, transformers, memory, switchgear, cable trays, chillers and batteries – and a supply constraint in a single critical component could act as a brake on everything else. We are investing in many of these critical enabling industries, but we are being disciplined on valuation – we see risk in highly rated AI-related stocks which are vulnerable to a downshift in the pace of growth.

The AI revolution will continue to be a double-edged sword for sustainability in 2026. On one side the energy footprint of AI is enormous and growing. While renewables will meet some of this demand (we expect hyperscalers will invest even more in renewable energy Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) seeking to avoid criticism that AI = more climate pollution) a good portion will also be met by fossil fuels since the lead times for new nuclear capacity remain long. So, as AI deployment expands, we expect it to boost short-term carbon emissions. On the other side, AI offers powerful tools to advance sustainability: 2025 already saw AI used to optimise energy systems and supply chains.

In 2026, we anticipate AI applications will help cut emissions – for example, smarter grid management to integrate renewables, AI-driven designs for more efficient buildings or EV batteries, better climate modelling and precision agriculture using AI. The social impacts of AI are arguably going to be far more consequential than its environmental impacts. From economic productivity, and the pace of innovation, to employment and broader societal impacts, AI stands to be one of most disruptive social phenomena since the agricultural and industrial revolutions. We expect there to be both extreme positives and negatives and there will be intense debate around the extent of government intervention and regulation. There will be ever greater scrutiny and challenge on responsible AI, and companies that do not do enough to prevent social harm could lose their license to operate. Just because COP 30 was a failure doesn’t mean clean technology secular investment trends are over. In fact, it is quite the opposite. Clean technology secular investment trends are in rude health, and even accelerating, driven by a strong backdrop in overall energy demand growth, cost competitiveness in many markets (solar and Chinese EVs in particular are highly competitive), and unwavering corporate commitment to decarbonisation.

We expect another record year for renewable installations; global solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity could jump by well over 250 GW and wind power by ~100GW given project pipelines. That means new renewable capacity will dwarf new fossil capacity added – possibly 5x-10x as much clean power as new coal/gas power in 2026. On the transport front EV sales are likely to exceed 30% of global car sales with the upshot that oil demand for passenger vehicles may peak soon.

Conclusion: Keep calm and compound on

In conclusion, we believe the secular investment trends associated with sustainable investments remain very much intact. Liquidity and monetary conditions appear supportive for equity markets, and we may well see another strong year for many of our investment themes. Importantly, rising emissions do not signal the end of the energy transition – rather, they underscore the imperative to accelerate investment in sustainable technologies.

Looking at the bigger picture, we believe that we are at the dawn of a new age, where the impact of AI across the physical world will create myriad products and markets, hitherto unimagined – just as the advent of smart phones opened up a whole new world of possibilities and enterprises that could not have been forecast previously.

Ultimately, this exciting phase for the world means that we want to be “long capital” while remaining vigilant of any potential shifts in growth trajectories.

Keep calm and compound on – the case for sustainable growth remains as compelling as ever, and we hope 2026 can reinforce our view by rewarding patience and commitment to the cause.

1Source: IRENA, ‘Global Landscape of Energy Transition Finance’ (2025).

2Source: Goldman Sachs, ‘AI to drive 165% increase in data center power demand by 2030’, 4 February 2025.

Asset allocation: The allocation of a portfolio between different asset classes, sectors, geographical regions, or types of security to meet specific objectives of risk, performance, or time horizon.

Benchmark: A standard (usually an index) that an investment portfolio’s performance can be measured against. For example, the performance of a UK equity fund may be benchmarked against the FTSE 100 Index, which represents the 100 largest companies listed on the London Stock Exchange.

Capital expenditure: Money invested to acquire or upgrade fixed assets such as buildings, machinery, equipment, or vehicles in order to maintain or improve operations and foster future growth.

Circular design: The practice of creating durable, reusable, repairable and recyclable products that generate zero waste to support a circular economy.

Circular economy: An economy where markets provide incentives to reuse products and materials, rather than scrapping them and extracting new resources. All forms of waste are returned to the economy or used more efficiently.

Equity: A security representing ownership, typically listed on a stock exchange. ‘Equities’ as an asset class means investments in shares, as opposed to, for instance, bond. To have ‘equity’ in a company means to hold shares in that company and therefore have part ownership.

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG): Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factors relate to the quality and functioning of the natural environment, the rights, well-being and interests of people and communities, and the governance of companies & their stakeholders.

Hyperscalers: Companies that provide infrastructure for cloud, networking, and internet services at scale. Examples include Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure, Meta, Alibaba Cloud, and Apple.

Liquidity/Liquid assets: Liquidity is a measure of how easily an asset can be bought or sold in the market. Assets that can be easily traded in the market in high volumes (without causing a major price move) are referred to as ‘liquid’.

Neocloud: A cloud provider that primarily offers GPU-as-a-Service (GPUaaS). Neoclouds concentrate on providing infrastructure specifically tailored to the demanding requirements of data-intensive workloads – particularly those related to AI, machine learning (ML), and analytics.

Return on equity (ROE): A company’s net income (income minus expenses and taxes) over a specified period, divided by the amount of money its shareholders have invested. It is used as a measurement of a company’s profitability compared to its peers. A higher ROE generally indicates that a management team is more efficient at generating a return from investment.

Valuation metrics: Metrics used to gauge a company’s performance, financial health, and expectations for future earnings, e.g. P/E ratio and ROE.

Volatility: The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security, or index, moves up and down. If the price swings up and down with large movements, it has high volatility. If the price moves more slowly and to a lesser extent, it has lower volatility. The higher the volatility, the higher the risk of the investment.

All opinions and estimates in this information are subject to change without notice and are the views of the author at the time of publication. Janus Henderson is not under any obligation to update this information to the extent that it is or becomes out of date or incorrect. The information herein shall not in any way constitute advice or an invitation to invest. It is solely for information purposes and subject to change without notice. This information does not purport to be a comprehensive statement or description of any markets or securities referred to within. Any references to individual securities do not constitute a securities recommendation. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

Whilst Janus Henderson believe that the information is correct at the date of publication, no warranty or representation is given to this effect and no responsibility can be accepted by Janus Henderson to any end users for any action taken on the basis of this information.