Navigating the shifting EM debt landscape

Thomas Haugaard, Portfolio Manager, discusses shifts in the emerging markets debt hard currency investment landscape and the team’s investment thoughts on navigating the asset class in an uncertain global environment.

12 minute read

Key takeaways:

- Developing and emerging economies are making progress on recovering from the economic shocks of the past three years, with our analytical forecasts indicating a slight uptick in overall credit quality in the EM debt hard currency (EMDHC) space.

- Dispersion and dislocations in the EMDHC universe remain high, presenting active managers with an opportunity to identify idiosyncratic value and diversification opportunities against the backdrop of an uncertain global macro environment.

- Some spread widening is likely near term from the slightly tight levels currently, but we still see EMDHC as a relatively bright spot in terms of carry, economic growth dynamics relative to the rest of the world, increasing scope for monetary easing and the likelihood, based on historical precedent, that the end of Fed tightening is a tailwind for EMDHC bonds unless it leads to a more significant slowdown in the US economy.

Today, developing countries are still working through the effects of the unprecedented economic shocks of the past three years. COVID, as well as contributing to inflation, created dislocations globally. The Ukraine-Russia conflict, fuelling higher commodity and food prices, disproportionally hit commodity importers and poorer countries in the EM universe.[1] Meanwhile, the second order effects of aggressive US monetary tightening aimed at taming inflation (including US dollar strength; higher US Treasury yields), continue to feature in the financial stresses dogging various weaker EM countries servicing hard currency denominated sovereign debt or seeking access to capital markets.[2]

High dispersion and desynchronisation

A notable aspect of these shocks is that their impact country-to-country has been anything but uniform. This is due to factors such as demographic differences, the different health policy responses to COVID, different fiscal and financial policies (some countries reacted with significant fiscal stimulus measures; others did not), different adaptive capabilities and the asymmetrical impact of these shocks on poorer developing economies.

We now have a high level of dispersion or dislocation across the global economy. A good example of this is China. Back in 2022, China cut key interest rates – and then again 2023 – against a backdrop of disruptions to trade, manufacturing and consumer spending, following its harsh zero-COVID policy.[3] In 2023, despite China’s much heralded reopening, we saw China slashing its growth target to a multi-decade low of “around 5%” for 2023, and even that target may not be achieved, according to several economists.[4]

This historically high dispersion is also evident within the EM universe when you look at credit risk ratings and credit spreads among EM countries. A big gap exists between the Investment Grade (IG) countries – financially strong countries like some higher income Middle Eastern countries that have benefited from rising commodity prices in recent years – and a group of countries (bigger than in the past) in the high yield sovereign bucket that are distressed or facing significant funding issues. As at 31 August 2023, spreads on IG sovereigns are well below their long-term averages, partly influenced by index composition changes in recent years, while spreads on high yield sovereigns – despite significant spread compression in the CCC rating band since March 2023 – remain above historical averages.[5]

From an investment perspective, as investors in EM hard currency debt, we believe the prudent response to this current high level of desynchronisation is to be diversified across different types of economic structures and economic policy responses as economies transition to something that is hopefully a bit more stable. Diversification, at least from our perspective, seems even more valuable than in the past.

Fiscal consolidation needed, but progress is evident despite tight social constraints

The rise in debt levels and tougher external financing conditions have increased pressure on many EM countries and inevitably brought scrutiny to their primary balances. Most emerging markets continue to have fiscal deficits wider than their pre-COVID trends and thus some fiscal consolidation is needed to get back to where things were before COVID.[6] Notably, debt-related issues have impacted countries like Zambia, Sri Lanka, Ghana, Pakistan, Tunisia, Egypt, El Salvador, Kenya and Lebanon. The risk of broader contagion from the group of distressed countries to the overall EM debt asset class is, in our view, limited. Sentiment has been lifted by constructive news on a debt restructuring agreement between official creditors and Zambia – cheered as a success for the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments initiative set up during the pandemic to help streamline debt restructurings; approval of an International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme for Pakistan; and progress on local debt restructurings in Ghana and Sri Lanka. While there is still a long road ahead to regain market access, recent progress bodes well for future restructuring processes.

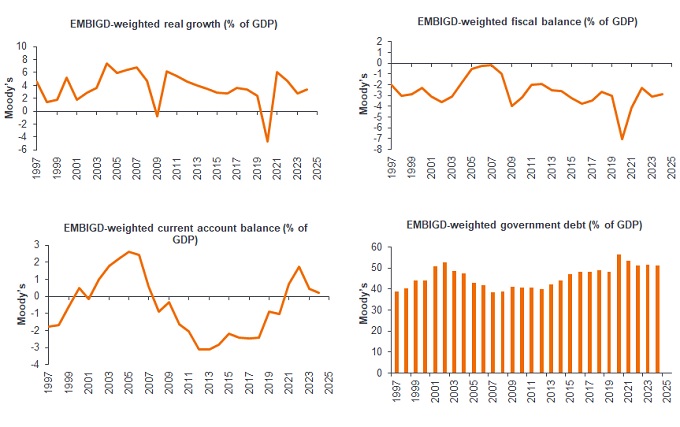

While debt accumulation in China has continued to reach new highs, this skews the picture for emerging markets where in fact the average debt-to-GDP on an EMBI-weighted basis has fallen from the peak in 2020 (Exhibit 1 – chart 4).

Exhibit 1: The debt profile for emerging markets has improved

Source: Moody’s, JP Morgan, 1 January 1997 to 30 June 2023. EMBIGD, the JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index, tracks liquid US dollar emerging market fixed and floating-rate debt instruments issued by sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities. There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Overall credit quality expected to improve slightly

While a slowing global economy (weaker external demand) does weigh on emerging markets, our proprietary forward-looking credit ratings model indicates a small improvement in overall credit quality for the EM hard currency universe, as represented by the JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index (EMBIGD).

Key positives in this respect include relatively good EM growth dynamics in aggregate, and ample prospects for monetary easing. Our base case is that the emerging market/developed market economic growth differential shifts significantly higher in 2024 given the widening disparity in forecasted global growth dynamics.[7] Many EM countries also have ample scope for monetary policy easing due to the higher starting point for real rates and improving inflation dynamics.[8]

Diamonds in the rough – pockets of opportunity

Although spreads in the IG segment are well below long-term averages, pockets of opportunity (reasonably attractive value) remain, particularly in the high yield segment among single-B and double-B rated credits, but on a case-by-case basis. Specific opportunities include countries undertaking longer-term reforms, value opportunities among sovereigns moving forward successfully with debt restructuring, and idiosyncratic opportunities in smaller countries in the frontier space.

Eastern Europe: Among the countries we have been investing in longer term and continue to be invested in are “reform stories” and stories with some kind of fiscal policy anchor. Currently, one of the biggest reform stories in the EM space is Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan is basically a zero-to-hero story from an autocratic dictatorship some years ago to what resembles a transition economy; one that has adopted more market-friendly reforms and is on a path of to a more market-oriented structure. Added to that, the country has relatively little debt and has large external buffers (substantial reserves). It is also a major exporter of gas, copper, gold and many things that the world needs.

Asia: Economies in Asia are typically well-positioned for the US-China rivalry and the consequent de-risking of supply chains globally. An example of a good reform story in Asia has been Indonesia. The country is facing an election next year, so this is a country we will be following closely. So far, continuity is our base case, as most contenders for the presidency are somewhat aligned with the reform-agenda of outgoing president Jokowi. Elections in Indonesia are no longer as disruptive as in the past, and the economy is still expected among the fastest growing in EM even in an election year.

Elsewhere in Asia, one country that we have long invested in is Mongolia. Located in the backyard of China, Mongolia is commodity rich and its cost of extracting these resources is low. The country also has reasonably sound economic policies and good relationships with multilaterals like the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Sub-Saharan Africa: We see a number of opportunities in Sub-Saharan Africa. IMF programmes are basically sealed in most of these countries after seeing financing costs to unpleasant levels. IMF presence introduces a degree of comfort regarding the direction of policy.

Among the countries we have visited on research trips in the past and which we have invested in for many years are high-growth economies like Benin, Senegal and Ivory Coast. We like countries that are growing quickly because higher growth makes fiscal consolidation that much easier, even in a post-COVID environment where social constraints have tightened as poverty and broad social conditions have deteriorated.

These three countries now have IMF programmes, which means that policies are hopefully changing for the better. This could lead to lower funding costs and a normalisation of market access. The IMF not only helps with financial relief; that money also comes with conditionalities on how to ensure that a country has market access, which supports having relatively good policies. Currently, the outlook for Ivory Coast and Senegal is less clear than that for Benin, given upcoming elections in both these countries.

Looking ahead

The global market environment, risk sentiment and growth dynamics are among the key drivers of EM debt. Post the banking tremors earlier in 2023, we have seen risk appetite improve globally as the US economy has shown resilience, particularly labour markets, along with progress on inflation. Looking at the move higher in US Treasury yields since March 2023 and the degree of EMBI spread-tightening (once adjusted for the distressed CCC-and-below segment), markets are currently (as at 31 August 2023) pricing in a soft landing/no landing for the US economy.

Our view on the macro backdrop and outlook is not so benign. Economic momentum in other major economies has worsened – with Germany in technical recession and the Chinese economy having deteriorated. We expect the Chinese authorities to adopt more targeted fiscal policies to support balance sheets, but the property market slump has hurt confidence. Elevated youth unemployment and an unwillingness of households to spend savings also remain persistent headwinds. Within the EM space, this will likely weigh on commodity exporters to China.

Our base case is for a rangebound US dollar, China muddling through and EM a bright spot in a relative sense – with growth accelerating in 2024, allowing for some fiscal consolidation and selective value in EM hard currency debt.[9] Our assumption is that risk aversion, an important input to model sovereign credit spreads, is more likely to move higher in the coming three to six months, which implies pressure on market spreads overall in that timeframe. With that in mind, we support a more defensive strategy, from a credit risk (beta) perspective, with a focus on maintaining the yield/carry through overweight positions in select high yield issuers.

That said, we believe today’s higher EMDHC yields will help underpin support from EM dedicated investors. Meanwhile, progress on inflation buoys our conviction that US Treasury yields could be a supportive tailwind for the asset class next year. Typically, when the Fed stops tightening, the following couple of years have delivered solid total returns for EMD.

—–

[1] By and large, developing countries are vulnerable to rising food, fuel and medicine prices. More than half of the countries classed as developing are commodity importers.

[2] A strengthening US dollar means countries that have issued debt denominated in US dollars see their debt repayments increase relative to the size of their respective economies.

[3] In August 2023, the People’s Bank of China slashed its 1-year loan prime rate (LPR) by 10 basis points to a record low of 3.45%. Source: Trading Economics, Y Charts.

[4] Data released in Q3 of 2023 suggests a fading rebound in China from the reopening of its economy at end-2022. Nomura Holdings Inc., for example, has lowered its 2023 growth forecast for China to 4.6%. Source: Bloomberg, 18 August 2023. In a similar vein, Morgan Stanley economists have revised their China growth forecast down to 4.7% for 2023 and 4.2% for 2024. Source: Morgan Stanley, 15 September 2023.

[5] Index composition here refers to the composition of the JP Morgan EMBIG Diversified Index. The Emerging Market Bond Index Global Diversified (EMBIGD) is a widely followed and uniquely weighted (country weights capped at 10%) USD-denominated emerging markets sovereign index. CCCs refer to bonds rated CCC by a credit rating agency. Credit ratings refer to the assessment by a credit rating agency as to the creditworthiness of the entity issuing the bond – in other words, the ability of the issuing entity to meet its financial obligations, including its bond payments. Bonds rated CCC are considered speculative, or non-investment grade.

[6] Fiscal consolidation describes government policy intended to reduce deficits and the accumulation of debt. Fiscal consolidation is often a balancing act involving tough choices. On the one hand, high debt leaves countries exposed to interest rate shocks, limits their capacity to respond to future shocks and reduces long-term growth potential. On the other hand, reducing deficits by cutting spending or raising revenues can, and usually does, hamper growth.

[7] The International Monetary Fund, in its latest World Economic Outlook (dated 25 July 2023), projects that growth across advanced economies will slow from 2.7% in 2022 to 1.5% in 2023 and 1.4% in 2024. Conversely, EM and developing economies are expected to expand 4.0% in 2023 – in line with the 4% figure for 2022 – and rise to 4.1% in 2024. It is also important to remember that the EM investible universe includes frontier countries with growth rates in the mid-to-high single digits. Historically, an improving EM-DM differential has signalled stronger relative performance. Improving EM/DM growth differentials also suggest the likelihood of a more benign investment flow scenario in 2024.

[8] Recent policy rate cuts in China, Brazil, Chile and Costa Rica point to the prospect of a broader EM easing cycle in the coming months. The direction of policy interest rates in EM – some keeping rates on hold and others easing – is beginning to diverge with those in major developed countries, where rates still have a steady-to-upward bias.

[9] S&P Global Ratings Economics’ recession model implies that the probability of a recession starting within the next 12 months has moderated since the beginning of 2023 but remains elevated at 30-35%. Source: S&P Global Ratings, “Economic Research: U.S. Business Cycle Barometer: Recession Risk Still Elevated Amid Uncertain Growth Prospects”, 20 September 2023. The primary factor in the evolution of recession probability in S&P’s model is the inverted US yield curve, which, S&P says, has predicted seven of the past seven recessions.

Important information:

Beta measures the volatility of a security or portfolio relative to an index. Less than one means lower volatility than the index; more than one means greater volatility.

JP Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index Global (EMBI Global) tracks total returns for traded external debt instruments in the emerging markets.

US Treasury securities are direct debt obligations issued by the US Government. With government bonds, the investor is a creditor of the government. Treasury Bills and US Government Bonds are guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the United States government, are generally considered to be free of credit risk and typically carry lower yields than other securities.

High-yield or “junk” bonds involve a greater risk of default and price volatility and can experience sudden and sharp price swings.

Credit Spread is the difference in yield between securities with similar maturity but different credit quality. Widening spreads generally indicate deteriorating creditworthiness of corporate borrowers, and narrowing indicate improving.