A version of this article recently appeared in Forbes.

Recently, we learned we are less employed than we thought we were.

A quarter million jobs vanished, yet no one new was fired and no one new quit: Those jobs never existed in the first place. Only our estimate of the truth changed; not the truth itself.

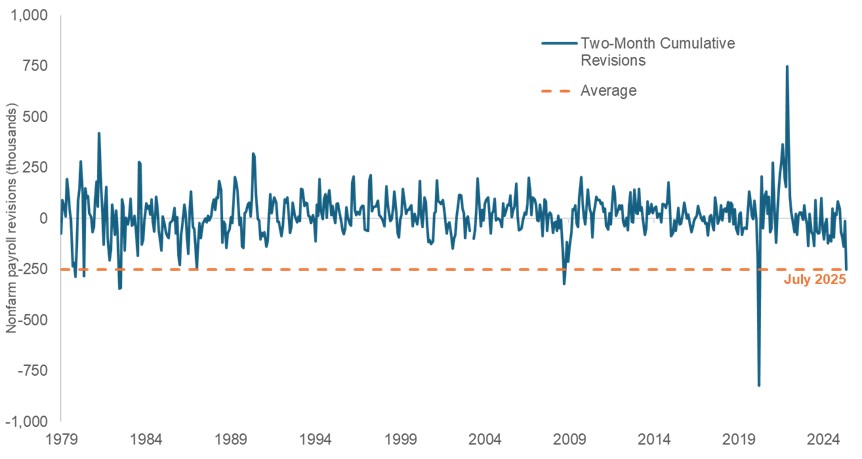

The two-month downward revision in jobs hadn’t been this negative since COVID, and before that, the Global Financial Crisis in October 2008. Before that, it hadn’t happened in decades, with only a handful of occurrences in 1979, 1980, and 1982.

Exhibit 1: Two-month U.S. nonfarm payroll revisions

The combined May and June jobs revisions reached levels seldom recorded and when they did were typically associated with major economic events like the Global Financial Crisis.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of July 2025.

In response, the U.S. equity markets fell between 1% and 2%, and Treasury bond yields collapsed, especially at the front end of the yield curve, as the market began pricing in a substantially higher expectation of Federal Reserve rate cuts. President Trump ordered the firing of the commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), citing “a lengthy history of inaccuracies and incompetence.” Should he have?

Revision history

Historically, revisions to employment data have been frequent and fairly modest. The monthly nonfarm payroll report is always revised twice, so there are three numbers: the preliminary estimate, the first revision the following month, and the second revision in the month following that. There are also annual revisions.

The average magnitude of the revisions since 1979 are between 40,000 and 60,000 jobs. Sometimes we find out we are more employed than we thought we were, and sometimes less.

For the July report, the May seasonally adjusted estimate was revised down 120,000 jobs from its first estimate and the June estimate was revised down 133,000 jobs. Each of those adjustments was historically extreme – worse than 95% of relevant monthly revisions since 1979. The two-month combination was basically a once-in-a-decade event, as the chart above shows.

These are big numbers. But ultimately, they are just one source of data. Jobs numbers help us think about the health of the economy, but they are just one piece of the puzzle.

What makes job numbers particularly useful is that they may be forward-looking: Rather than estimating historical consumer purchases, job creation can presage future spending. That’s why revisions could matter, too. Consider this analogy: You drive differently if you think your exit is three miles away than you do if you think it’s a quarter mile away.

But we can’t live our lives in the past, constantly revising what we used to think about ancient history. So, when should a revision of the past change your perspective of the future?

Estimates versus. reality

Surely, a revision of past data should have some effect. One famous quote attributed to John Maynard Keynes summarizes this view: “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

Of course, not all facts matter to the same degree, or at the same time. Yesterday’s future is tomorrow’s past. Eventually, other data should matter more than the jobs numbers. If the BLS announced an inadvertent and unnoticed typo in a jobs number from eight years ago, that should presumably have almost no effect on your views today, since so much additional data has already come in about spending, saving, production, consumption, inflation, and more.

In other words, those quarter million jobs either existed or did not. Estimates and revisions won’t change what actually happened. Even knowing the exact true number is only a proxy for the actual information you would be interested in. And as time has passed, other data have come out that may be more valuable than a more accurate – but more historically distant – estimate.

There is a devastating counterpoint, however, as anyone who has ever been in any kind of personal or professional relationship would know. If a piece of information about the ancient past can change or color your perception of the entire relationship, then almost no amount of time can reduce that emotional impact. In any fight with a loved one, the biggest pain isn’t whatever action they did or did not take, or your best estimate of that action, or even the revisions of your best estimates of their action. What matters is the possibility that they never loved you at all. Was it all a lie?

President Trump’s firing of the BLS commissioner may be controversial. But both the administration and its critics worry about the same thing: Data ought to be as accurate and objective as possible.

This issue is a lot like reading the news. The loud front pages say one thing, usually preliminary news. Later retractions or corrections are quiet and unnoticed. As a society, we can begin to split into and live in two different worlds: those who did not know the truth and did not see the retraction, and those who knew the truth or saw the retraction. Therefore, we no longer even have the same facts. Some of us begin to live in the hallucinated, unrevised, un-retracted world – a world much like the Mandela effect, where we swear we remember things that in fact never happened.

Trust is a fragile thing. A good-faith revision here or a retraction there can be fine. But if you notice a consistent bias or pattern in the revisions and retractions, if the errors are rarely in your favor, you may stop subscribing to that source of news or data. If you are in a relationship, you may look to end or fix it. If you are the President of the United States, you may seek a new commissioner. The primary challenge in each of these cases is the same: Trust much be restored

In the revision economy and the retraction life, beliefs can bend, but faith can snap.