Paul O’Connor, Head of the UK Multi-Asset Team, gives his reaction to the UK election result and what it means for the Brexit process.

For more than three decades, UK general elections have had only a modest impact on UK financial markets, with investors paying only fleeting attention as power flipped between centre-right and centre-left administrations. This one is different. This time, the two main parties presented the electorate with two highly polarised visions of the future. The stark choice offered here was between a Conservative Party offering a smooth, hard Brexit and the most radically left-wing UK Labour Party proposition for over 40 years.

Get Brexit done

Although the votes were not all counted at the time of writing, it is clear the electorate has given a huge victory to Boris Johnson’s Conservative government. The expected working majority of around 80 seats gives his government almost total control of parliament. This is a devastating rejection of Labour’s policies and rightly or wrongly will be taken as a strong vote for “getting Brexit done”, the dominant message of the Conservative campaign.

Continuity in economic policy

In terms of the traditional areas of economic policy, the Conservative victory clearly represents more continuity than change. While the details of Boris Johnson’s planned economic policies are still fairly scant, ambitions on the fiscal side have already been outlined in some detail in the September spending review. The big picture here is of a modest fiscal stimulus in 2020, boosting Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth by less than 0.5% in that year but with little additional thrust after that, given the pledge to balance the budget over a three-year window. Compared to the typical Conservative governments of recent years, the Johnson administration seems likely to tilt fiscal stimulus more towards government spending than taxation and more towards blue-collar Britain than higher earners and companies.

Financial markets are clearly breathing a sigh of relief today as they face a more conventional package of economic policies rather than the many radical aspects of Jeremy Corbyn’s plans. The direct impact on growth forecasts of the Conservative plans is likely to be marginally positive but barely enough to inspire economists to change growth forecasts, given some of the other influences that also now have to be taken into consideration. It is no surprise that financial markets are uncertain whether the next move in UK interest rates will be up or down.

Brexit – a game changer

Of course, this election was not really about traditional economic policies and nor will the aftermath be either. This election was all about Brexit. The choices that Boris Johnson’s government makes on this front will have substantial economic and political impacts on the UK and beyond for many years to come.

One thing we know is that the immediate priority of the new government will be to seek parliamentary approval for the withdrawal agreement to get the Brexit process formally started by the 31 January deadline. That previous hurdle is now simply a formality. Of course, the withdrawal agreement only covers the UK’s departure from the European Union (EU). That was meant to be the relatively easy bit of the process – it nevertheless involved over three years of intense political conflict. The bigger challenge and the greater uncertainty surrounds the next phase, when the EU and the UK get to work on establishing the terms for future relations in trade and other areas such as defence, security and foreign trade co-operation.

As things stand, the two sides have agreed on an end-2020 deadline for finalising a trade deal and a transition period until then which ensures that very little changes for business during this phase. The critical issue beyond that one-year time horizon is that the Conservative Party manifesto has pledged not to extend the transition period beyond 2020, which means that the UK looks set to engage the EU next year to negotiate a trade deal that can be completed by the end of 2020.

Bare-bones Brexit

Under this scenario, the UK looks set to exit the transition period with a bare-bones trade deal, similar to Canada’s free-trade with the EU. That deal would probably involve tariff-free trade in goods but with border checks and non-tariff trade barriers, reflecting the UK’s desire to achieve some form of regulatory independence. It is worth noting that the EU has a sizeable trade surplus in goods with the UK, measured at £94bn in 2018. However, in services, where the UK has run a trade surplus with the EU for over a decade, there is little hope for meaningful progress on establishing new trade relations in 2020. That will leave a large cloud of uncertainty overshadowing more than 80% of the UK economy, which means that this clean-break Brexit will effectively be quite a hard Brexit.

Fast and hard or soft and slow?

The big question here is whether Boris Johnson’s government will continue down this path, regardless of the adverse economic consequences or whether there will be a pivot towards a softer Brexit. The length of the transition period is a key indicator of the choice between a fast, hard Brexit or a softer and slower outcome. The most enthusiastic Brexiteers oppose many of the conditions associated with the transition period, such as financial contributions to the EU, free movement of labour and the UK remaining under the jurisdiction of the European court of justice. While the size of Boris Johnson’s majority gives him some scope to resist the hardliners and lean towards a more economically pragmatic Brexit, it is far from clear that this is a path he wants to take. It is equally plausible that he will view the threat of a no-deal exit at the end of 2020 as leverage in the negotiations and will show no sign of changing course until late in 2020, if at all.

In a rut

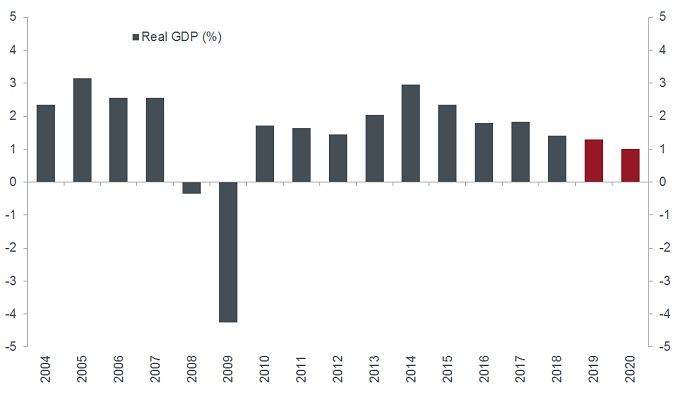

Based on what we know so far, the policy package of the new government seems unlikely to lift the UK economy out of its post-referendum torpor. Brexit-related uncertainty and weakening global growth have weighed heavily on UK macro momentum in recent years. UK GDP has not grown faster than 2% in real terms since 2015 and growth has slowed every year since then. Consensus forecasts are for growth of just 1.3% this year and 1% next year, extending a 7-year trend of deceleration. While some hold hope for a lift in business confidence from the government’s fiscal stimulus and the near-term reduction in political uncertainty, we see limited scope for a big uplift in sentiment and investment unless the government extends the Brexit transition period.

UK GDP growth and consensus forecasts (%)

Source: Bloomberg, as at December 2019.

Source: Bloomberg, as at December 2019.Notes: Red bars and dotted line represent current median consensus forecasts.

Fade the surge

While the election certainly delivered a greater than expected majority for the Conservative Party, the market response to this outcome was quite predictable. The short-term impact is a clear relief rally, as markets focus on dispelling the risks associated with a Jeremy Corbyn-led government. Sterling has always been the clearest barometer of investor sentiment with regard to Brexit. Here, we would note that the pound has now bounced over 12% from its October low, taking it to around 4% below its average level in the five years before referendum. We do not see much scope for sustained upside in sterling from here, given the sizeable uncertainties still surrounding the Brexit process and the ongoing adverse impact of Brexit on the UK economy.

Glossary:

Fiscal: Connected with government taxes, debts and spending. Fiscal policy is government policy related to setting tax rates and spending.

Leverage: The use of borrowing to increase exposure to an asset/market. This can be done by borrowing cash and using it to buy an asset, or by using financial instruments such as derivatives to simulate the effect of borrowing for further investment in assets.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.