Rather than viewing this week’s policy-setting meeting by the Federal Reserve (Fed) as a discrete event, it could be more aptly characterized as a postscript to December’s rate decision.

When announcing what was framed as a “hawkish rate cut”, the central bank telegraphed that that 25-basis point (bps) reduction in the overnight rate would be the last until greater clarity emerged on the trajectories of inflation and the U.S. labor market. That decision raised some eyebrows, as many wondered why cut at all when neither side of the Fed’s dual mandate seemed to be tipping into territory where greater accommodation was merited.

Rather than rehash that decision, we think it’s best to do what the Fed states underpins its actions: follow the data. As indicated in this decision’s accompanying statement and recent data releases, the weakness in the U.S. labor market that forced the Fed off the sidelines in September has stabilized and inflation remains sticky. Consequently, the Fed had little alternative but to exercise the patience it intimated in December.

Surprisingly steady

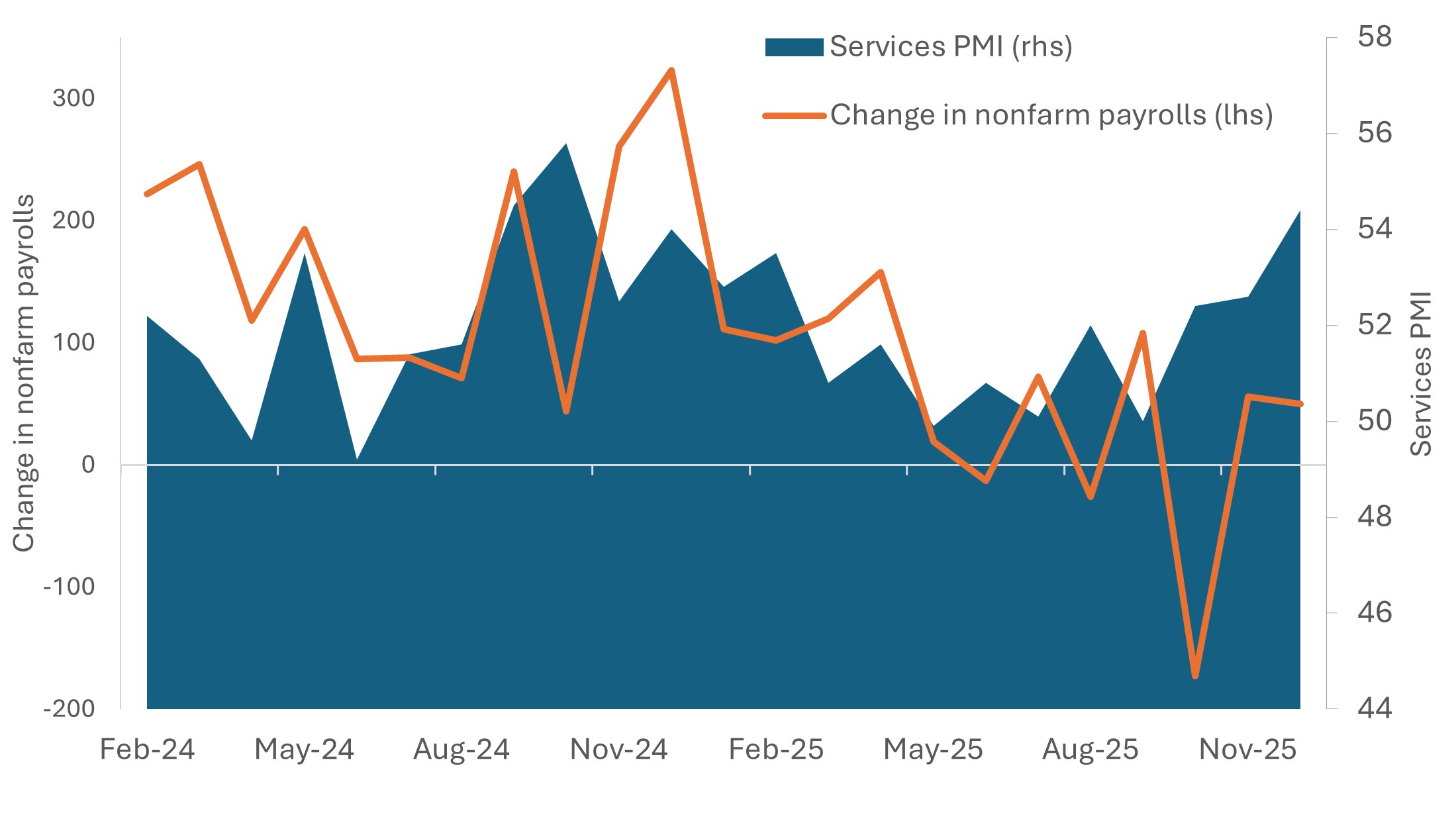

Starting with what alarmed the Fed last year, payroll gains have remained worryingly weak but, importantly, have yet to roll over. The 49,000 monthly additions averaged across 2025 are less than half of what is largely considered necessary to absorb workers into an expanding economy. Still, payroll gains have yet to string together successive months of contraction.

Similarly, while off its post-pandemic low, the layoffs rate, at 1.1%, resides below its long-term average. This possibly fragile equilibrium is reinforced by the four-week average of weekly initial jobless claims falling to just over 200,000 after having spent much of mid-2025 above 230,000. A qualifier must be inserted, however, as visibility into labor market health has been hampered by both the late-year government shutdown and large-scale changes to the U.S. immigration system, which may affect both supply and demand dynamics.

While nonfarm payroll gains averaged a meager 49,000 in 2025, the important services sector ventured further into expansion territory late in the year, portending a potential stabilization in the labor market.

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, Bloomberg, as of 28 January 2026. Note: Based on Institute for Supply Management’s services purchasing index.

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, Bloomberg, as of 28 January 2026. Note: Based on Institute for Supply Management’s services purchasing index.

Likely righting the labor market has been sturdier-than-expected economic growth. The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tracker indicates the U.S. economy expanding at an impressive annualized 5.4% clip in the first quarter. Other indicators appear less sanguine, but while manufacturing surveys remain mired in contraction territory, the services sector – as measured by the Institute for Supply Management’s Purchasing Manager’s Index, has climbed higher into expansion for four successive months.

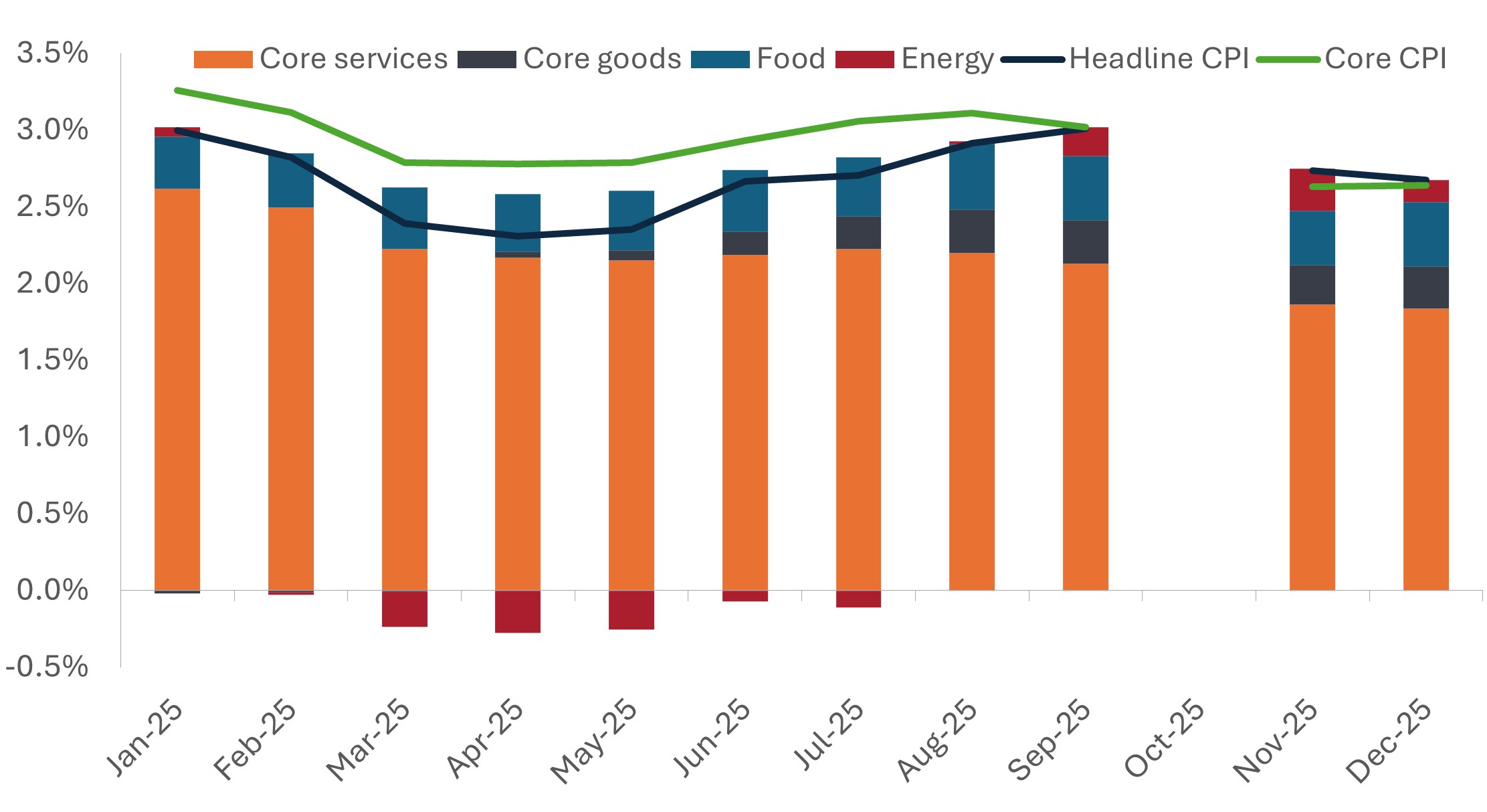

With the labor market stabilizing, the Fed’s decision to stand pat was further buttressed by inflation still residing well above the central bank’s 2.0% target. The headline consumer price index fell only modestly in December – to 2.68% –while the core rate held steady at 2.6%.

While core services – a main driver of inflation – saw its contribution to headline inflation fall over 2025, core goods notably started to increase – likely a consequence of tariffs.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 28 January 2026. Note: October inflation data unavailable due to government shutdown.

As expected, core services comprised the largest share of the headline rate. But what likely captured the Fed’s attention is the persistent increase in the contribution of core goods to aggregate inflation in the months since President Trump’s Liberation Day tariff barrage. To be determined is whether these duties represent a one-time increase in prices or are sufficient to solidify a much-feared increase in inflation expectations. Such an outcome risks morphing into an upward spiral and can alter consumer behavior, especially in lower-income quintiles that are more affected by rising prices.

What to watch next

With the acute threat of the labor market rolling over having subsided, the Fed’s plan of taking a wait-and-see stance through much of 2026 remains intact. At its December conclave, surveyed members anticipated only one 25 bps cut this year. Futures markets see the possibility of a second reduction by year’s end. Neither scenario reflects impending doom.

Stabilization has also bought the Fed time to better gauge tariffs’ knock-on effects on consumer prices. Had employment weakness accelerated, the Fed would have faced the dilemma of easing policy – possibly before the inflation battle was won. Should range-bound inflation resume its downward trend – a condition possibly premised on goods prices and the U.S. dollar stabilizing – the Fed will likely have the latitude to maintain what we view as a dovish bias.

That stance is inextricably linked to perhaps the most widely followed drama in economic policy circles: Who will succeed Chairman Jerome Powell, and how will that change impact future monetary policy? While President Trump’s preference is a more accommodative, possibly pliant, central bank, the staggering of senior members’ tenures likely makes outside influence easier said than done. It is worth noting, though, that dark-horse candidate Christopher Waller was one of two voters opting for a rate cut at this meeting.

Staying invested, limiting risks

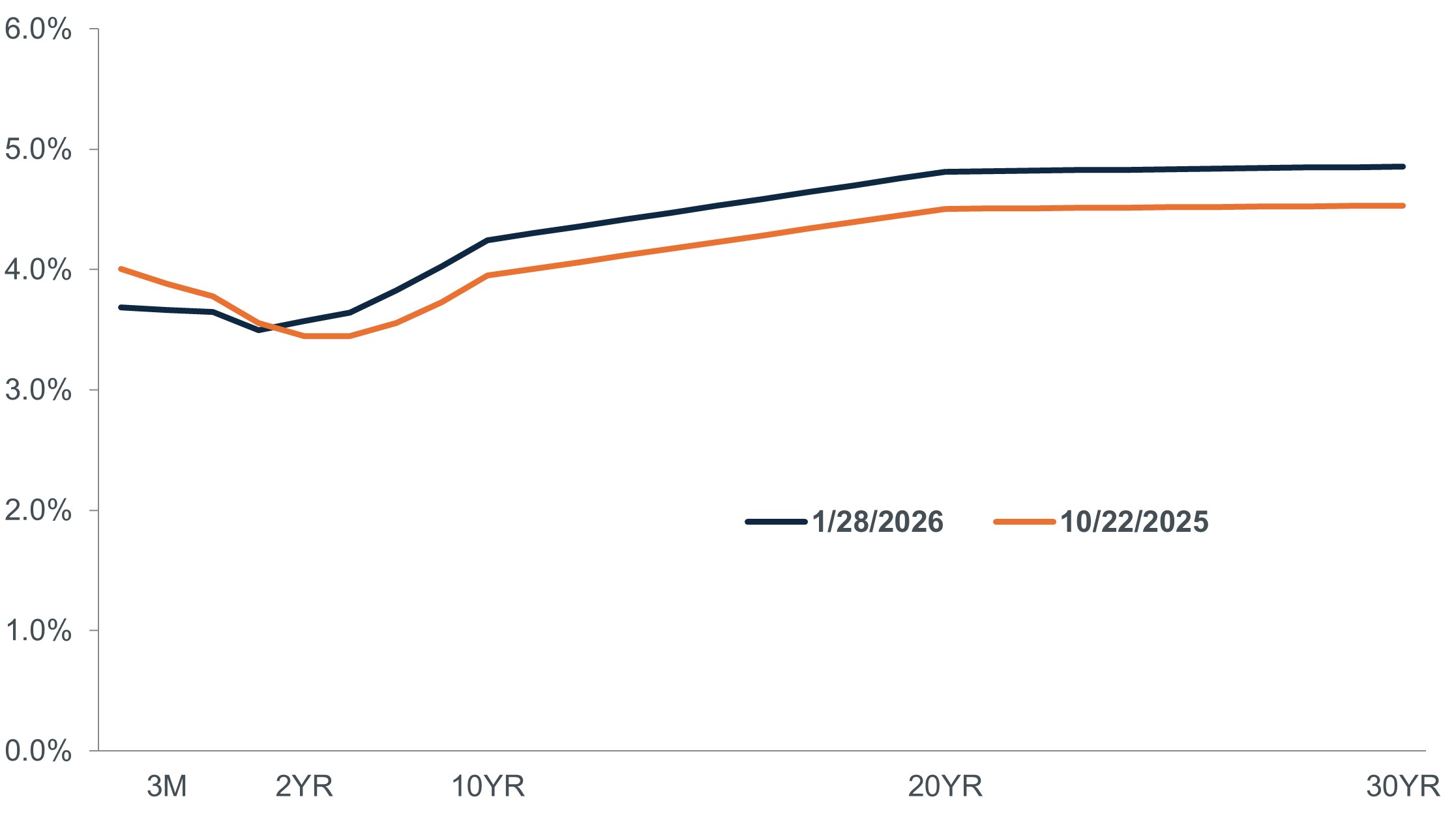

In the absence of either economic contraction weighing on corporate health or accelerating inflation inflicting capital losses, bond investors are looking at the opportunity to stay invested in range-bound markets and harvesting yields that remain attractive. We consider this mostly the case with shorter- to mid-dated maturities, as the overnight rate, which tends to have greater influence on the front end of the curve – in Chairman Powell’s words – is likely near the upper end of its range moving forward.

Longer-dated yields have historically proven more volatile and thus merit greater circumspection. In contrast to the range-bound 2-year yield – oscillating between 3.40% and 3.65% – that of the 10-year note has risen 30 basis points since its October low, resulting in the steepest yield curve since 2021. The culprit for this move is uncertain. It could reflect the higher projected U.S. debt burden, the prospect of a less independent Fed, or the “sell America” trade that is a consequence of norm-breaking trade and security policies rattling domestic and foreign investors alike.

With the Fed having been expected to be on hold, the front end of the Treasuries curve has been rangebound while longer-dated maturities have had to contend with factors like policy volatility and U.S. federal debt.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 28 January 2026.

Even with a steeper yield curve offering potentially higher returns, investors would have to be comfortable with assuming a higher degree of economic and geopolitical risk when allocating to longer-dated maturities. We believe short- to-mid-dated notes continue to offer attractive carry with lower levels of volatility. And while sticky inflation likely diminishes the chance of shorter-dated bonds benefiting from an imminent rate cut, we see little evidence of the type of economic acceleration that could send inflation higher, forcing the Fed to reverse course.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

10-Year Treasury Yield is the interest rate on U.S. Treasury bonds that will mature 10 years from the date of purchase.

Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point. 1 bp = 0.01%, 100 bps = 1%.

Carry is the excess income earned from holding a higher yielding security relative to another.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) is an unmanaged index representing the rate of inflation of the U.S. consumer prices as determined by the U.S. Department of Labor Statistics.

Duration measures the sensitivity of a bond’s or fixed income portfolio’s price to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates and vice versa.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. Monetary policy tools include setting interest rates and controlling the supply of money.

Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI) is an index of the prevailing direction of economic trends in the manufacturing and service sectors, based on a survey of private sector companies.

Volatility measures risk using the dispersion of returns for a given investment. The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index moves up and down.

Yield curve plots the yields (interest rate) of bonds with equal credit quality but differing maturity dates. Typically bonds with longer maturities have higher yields.

U.S. Treasury securities are direct debt obligations issued by the U.S. Government. With government bonds, the investor is a creditor of the government. Treasury Bills and U.S. Government Bonds are guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the United States government, are generally considered to be free of credit risk and typically carry lower yields than other securities.

Queste sono le opinioni dell'autore al momento della pubblicazione e possono differire da quelle di altri individui/team di Janus Henderson Investors. I riferimenti a singoli titoli non costituiscono una raccomandazione all'acquisto, alla vendita o alla detenzione di un titolo, di una strategia d'investimento o di un settore di mercato e non devono essere considerati redditizi. Janus Henderson Investors, le sue affiliate o i suoi dipendenti possono avere un’esposizione nei titoli citati.

Le performance passate non sono indicative dei rendimenti futuri. Tutti i dati dei rendimenti includono sia il reddito che le plusvalenze o le eventuali perdite ma sono al lordo dei costi delle commissioni dovuti al momento dell'emissione.

Le informazioni contenute in questo articolo non devono essere intese come una guida all'investimento.

Non vi è alcuna garanzia che le tendenze passate continuino o che le previsioni si realizzino.

Comunicazione di Marketing.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- Gli emittenti di obbligazioni (o di strumenti del mercato monetario) potrebbero non essere più in grado di pagare gli interessi o rimborsare il capitale, ovvero potrebbero non intendere più farlo. In tal caso, o qualora il mercato ritenga che ciò sia possibile, il valore dell'obbligazione scenderebbe.

- L’aumento (o la diminuzione) dei tassi d’interesse può influire in modo diverso su titoli diversi. Nello specifico, i valori delle obbligazioni si riducono di norma con l'aumentare dei tassi d'interesse. Questo rischio risulta di norma più significativo quando la scadenza di un investimento obbligazionario è a più lungo termine.

- Alcune obbligazioni (obbligazioni callable) consentono ai loro emittenti il diritto di rimborsare anticipatamente il capitale o di estendere la scadenza. Gli emittenti possono esercitare tali diritti laddove li ritengano vantaggiosi e, di conseguenza, il valore del Fondo può esserne influenzato.

- Il Fondo potrebbe usare derivati al fine di conseguire il suo obiettivo d'investimento. Ciò potrebbe determinare una "leva", che potrebbe amplificare i risultati dell'investimento, e le perdite o i guadagni per il Fondo potrebbero superare il costo del derivato. I derivati comportano rischi aggiuntivi, in particolare il rischio che la controparte del derivato non adempia ai suoi obblighi contrattuali.

- Qualora il Fondo detenga attività in valute diverse da quella di base del Fondo o l'investitore detenga azioni o quote in un'altra valuta (a meno che non siano "coperte"), il valore dell'investimento potrebbe subire le oscillazioni del tasso di cambio.

- Se il Fondo, o una sua classe di azioni con copertura, intende attenuare le fluttuazioni del tasso di cambio tra una valuta e la valuta di base, la stessa strategia di copertura potrebbe generare un effetto positivo o negativo sul valore del Fondo, a causa delle differenze di tasso d’interesse a breve termine tra le due valute.

- I titoli del Fondo potrebbero diventare difficili da valutare o da vendere al prezzo e con le tempistiche desiderati, specie in condizioni di mercato estreme con il prezzo delle attività in calo, aumentando il rischio di perdite sull'investimento.

- Il Fondo potrebbe perdere denaro se una controparte con la quale il Fondo effettua scambi non fosse più intenzionata ad adempiere ai propri obblighi, o a causa di un errore o di un ritardo nei processi operativi o di una negligenza di un fornitore terzo.

Specific risks

- Gli emittenti di obbligazioni (o di strumenti del mercato monetario) potrebbero non essere più in grado di pagare gli interessi o rimborsare il capitale, ovvero potrebbero non intendere più farlo. In tal caso, o qualora il mercato ritenga che ciò sia possibile, il valore dell'obbligazione scenderebbe.

- L’aumento (o la diminuzione) dei tassi d’interesse può influire in modo diverso su titoli diversi. Nello specifico, i valori delle obbligazioni si riducono di norma con l'aumentare dei tassi d'interesse. Questo rischio risulta di norma più significativo quando la scadenza di un investimento obbligazionario è a più lungo termine.

- Il Fondo investe in obbligazioni ad alto rendimento (non investment grade) che, sebbene offrano di norma un interesse superiore a quelle investment grade, sono più speculative e più sensibili a variazioni sfavorevoli delle condizioni di mercato.

- Alcune obbligazioni (obbligazioni callable) consentono ai loro emittenti il diritto di rimborsare anticipatamente il capitale o di estendere la scadenza. Gli emittenti possono esercitare tali diritti laddove li ritengano vantaggiosi e, di conseguenza, il valore del Fondo può esserne influenzato.

- Il Fondo potrebbe usare derivati al fine di conseguire il suo obiettivo d'investimento. Ciò potrebbe determinare una "leva", che potrebbe amplificare i risultati dell'investimento, e le perdite o i guadagni per il Fondo potrebbero superare il costo del derivato. I derivati comportano rischi aggiuntivi, in particolare il rischio che la controparte del derivato non adempia ai suoi obblighi contrattuali.

- Qualora il Fondo detenga attività in valute diverse da quella di base del Fondo o l'investitore detenga azioni o quote in un'altra valuta (a meno che non siano "coperte"), il valore dell'investimento potrebbe subire le oscillazioni del tasso di cambio.

- Se il Fondo, o una sua classe di azioni con copertura, intende attenuare le fluttuazioni del tasso di cambio tra una valuta e la valuta di base, la stessa strategia di copertura potrebbe generare un effetto positivo o negativo sul valore del Fondo, a causa delle differenze di tasso d’interesse a breve termine tra le due valute.

- I titoli del Fondo potrebbero diventare difficili da valutare o da vendere al prezzo e con le tempistiche desiderati, specie in condizioni di mercato estreme con il prezzo delle attività in calo, aumentando il rischio di perdite sull'investimento.

- Il Fondo potrebbe perdere denaro se una controparte con la quale il Fondo effettua scambi non fosse più intenzionata ad adempiere ai propri obblighi, o a causa di un errore o di un ritardo nei processi operativi o di una negligenza di un fornitore terzo.

- Oltre al reddito, questa classe di azioni può distribuire plusvalenze di capitale realizzate e non realizzate e il capitale inizialmente investito. Sono dedotti dal capitale anche commissioni, oneri e spese. Entrambi i fattori possono comportare l’erosione del capitale e un potenziale ridotto di crescita del medesimo. Si richiama l’attenzione degli investitori anche sul fatto che le distribuzioni di tale natura possono essere trattate (e quindi imponibili) come reddito, secondo la legislazione fiscale locale.