A Fed meeting where a 25 basis-point (bps) rate cut was largely baked in, without an accompanying Summary of Economic Projections, and in this instance, missing several data releases due to the government shutdown, seemed like a recipe for a fairly mundane affair.

That was not the case, however, as Fed Chairman Jerome Powell caught the attention of markets by intimating that a December rate cut was far from a “foregone conclusion.” While recent Fed speeches were peppered with talk of “balanced” risks, it was clear to many that, as evidenced by the resumption of cuts in September, the U.S. central bank had possibly become more vexed with a weakening labor market.

The decision

As had been highly telegraphed, the Fed reduced its benchmark overnight lending rate from an upper bound of 4.25% to 4.00%. Underpinning the move was softening labor data over the course of the year along with the reality that the policy rate was still well above the Fed’s favored gauge of core inflation, which sat at 2.91% at the time of its last report in August. In addition to a rate cut, doves were treated to the announcement that the Fed would end quantitative tightening, seeking to maintain a balance sheet level of roughly $6.6 trillion. For market doves, that was largely where the treats ended.

What could be interpreted as a hawkish trick came in the form of Chairman Powell’s press conference, where it was revealed that this decision was not unanimous. While the vote for a 50bps cut by Stephan Miran was expected as he’s midway through his Fed “residency”, Jeffrey Schmid’s choice for no change was more notable. Debates with Schmid and other like-minded voters were likely behind Powell’s emphasis that a December cut – something that had been heavily priced in by futures markets – was not a certainty.

Balancing the risks

By its own admission, the Fed finds itself in a tight spot as it seeks to calibrate monetary policy. Inflation risk is to the upside and labor market risk is to the downside; the Fed cannot prioritize both.

With inflation elevated but stable, the assumption was that stemming labor market softness took precedent. The recent large downward annual revisions, along with still-available private sector jobs data remaining on a downward trajectory, certainly merited attention. And tariffs – thus far – not pushing up inflation in a persistent manner gave the Fed latitude to address emerging labor market woes.

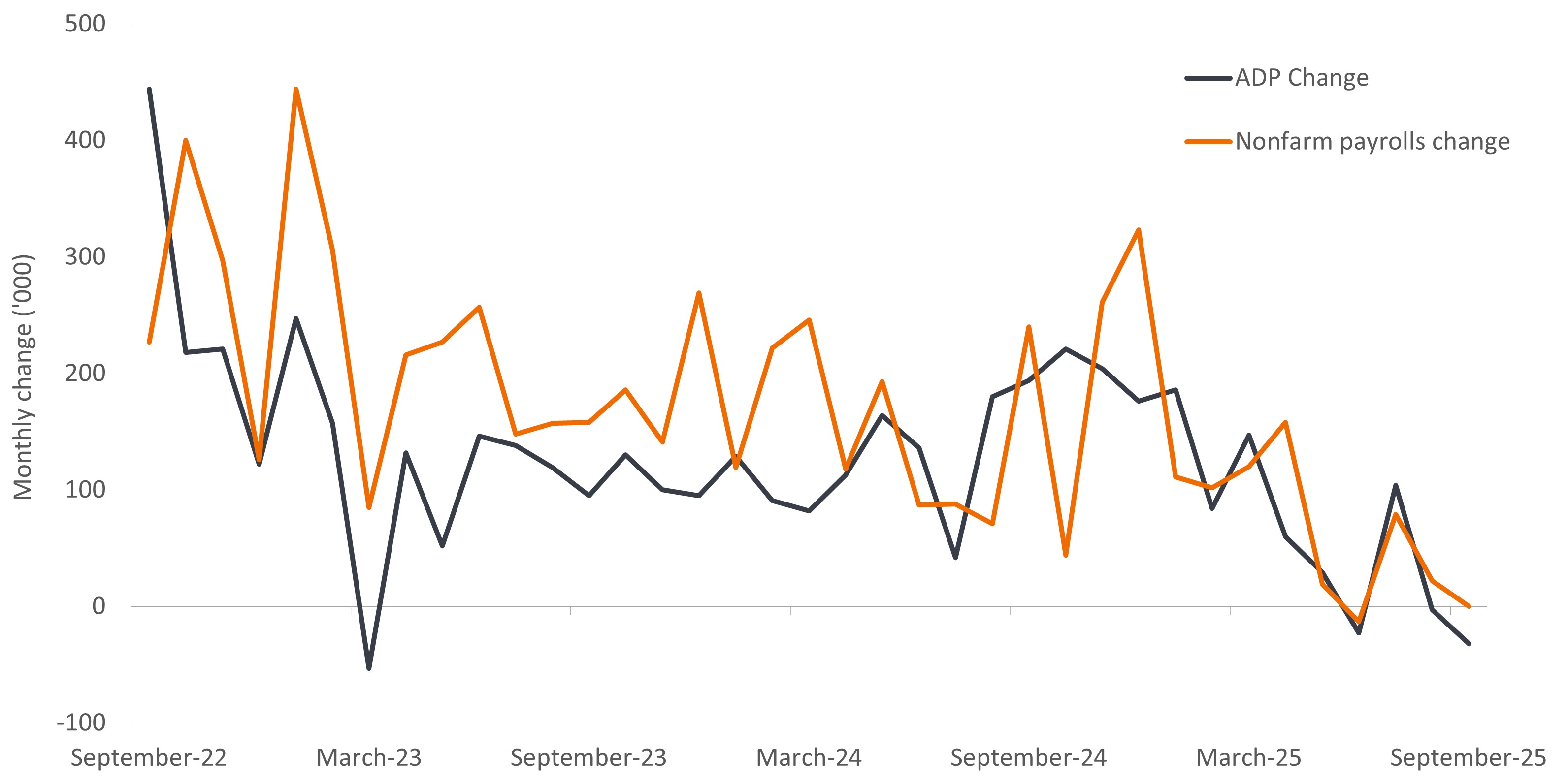

Exhibit 1: U.S. government and ADP labor market data

Still-available private payroll data echo the ongoing downward trend of government jobs data.

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, as of 29 October 2025.

So how can one interpret what appears to be mixed bag of policy prescriptions? A possible explanation is that the Fed is painfully aware not only of its fateful post-pandemic “transitory” inflation call but also its more dire 1970s policy error when it prematurely declared victory over inflation, thus causing a second – and fiercer – wave. Chairman Powell has been adamant that maintaining credibility is essential for Fed policy, and especially forward guidance, to be effective.

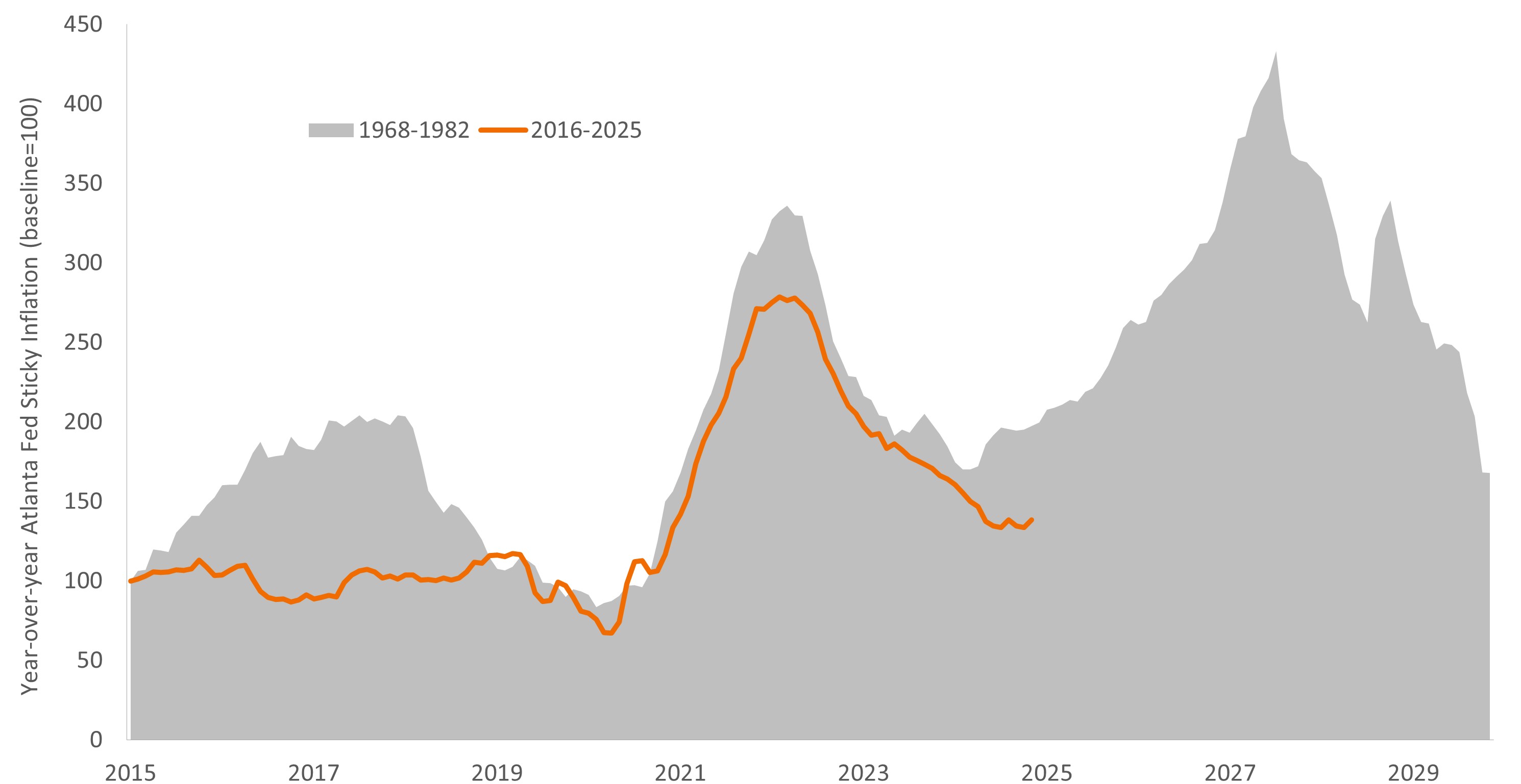

Exhibit 2: Trajectory of sticky U.S. inflation, 1970s and today

While seeking to support a softening labor market, the Fed likely remains aware of past policy errors of prematurely declaring victory over inflation.

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, as of 29 October 2025.

Another, equally likely, explanation is that the current economic environment merits a finely balanced policy stance. The U.S. economy is expected to grow in 2026, albeit at a slightly slower pace than this year. Still, the expansion has proven more resilient than anticipated, largely driven by personal consumption, the steady engine of the U.S. economy. But this reliance on household spending may be what caused the majority of the Fed to believe that at least one more rate cut in 2025 was necessary. A softening labor market in an economy dependent on personal consumption is a volatile combination and one that can roll over quickly.

Complicating matters is a convergence of forces that could swing the U.S. – and possibly global – economy one way or the other. In addition to spurring a historic investment cycle within the technology infrastructure sector, artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to unlock productivity gains – a key ingredient to economic growth. An unanswered question, though, is to what degree AI deployment will impact the size of the labor force. Federal policy, from immigration to tariffs, is also likely to influence the labor market and household spending decisions. On the positive side of the ledger, aggressive easing by many regions should prove supportive of growth, as should possible fiscal initiatives in China and Germany.

Awaiting clarity

A succession of policy prescriptions across developed markets may prove sufficient to extend the global economic cycle. At the very least, a divergence in growth trajectories presents fixed income investors with the opportunity to source duration and credit risk as dictated by local conditions. Higher-quality corporate credits could benefit from tailwinds in regions – like the eurozone – that were proactive in supporting flagging growth. In others where conditions merit additional policy support, investors can consider modestly extending duration.

Up until this meeting, the expectation was that U.S. duration would be at the top of the list for many bond investors. And while the Fed’s October decision did completely upend that tactic, it did remind investors that economic conditions are perhaps more uncertain than anticipated and that this still is a time for patience.

Until we gain further clarity, fixed income investors may want to consider fortifying their portfolios by seeking geographical diversification, identifying higher-quality corporate credits that stand do perform well even if their region’s (or global) economic cycle stalls, and only sourcing duration where the upside risks to inflation seem manageable.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Diversification neither assures a profit nor eliminates the risk of experiencing investment losses.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

Basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point. 1 bp = 0.01%, 100 bps = 1%.

Duration measures a bond price’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates. The longer a bond’s duration, the higher its sensitivity to changes in interest rates and vice versa.

Monetary Policy refers to the policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. It includes controlling interest rates and the supply of money.

Quantitative Easing (QE) is a government monetary policy occasionally used to increase the money supply by buying government securities or other securities from the market.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Marketing Communication.