Geopolitics and the importance of geography

The realignment of geopolitics is one of three macro drivers as we see them for investing through the next decade. Here, bestselling author, journalist, and broadcaster, Tim Marshall, explores why geography is so important in shaping global tensions, while Janus Henderson CEO Ali Dibadj provides his take on the implications for investors.

9 minute read

Key takeaways:

- Geography plays an important role in explaining the actions of world powers and the realignment of geopolitics.

- 2024 will be a pivotal year of elections – particularly significant given escalated tensions across the world stage.

- The actions of Russia, China, and the US will have meaningful implications for the global economy and changes need to be skilfully navigated by investors.

Tim Marshall was the Foreign Editor and then Diplomatic Editor for Sky News, reporting from various warzones and conflicts. He is the author of Prisoners of Geography, The Power of Geography, and most recently The Future of Geography: How Power and Politics in Space Will Shape Our World. Tim was a guest presenter at Janus Henderson’s 2024 investment conference in London. Here, he provides his views on the current tensions in geopolitics.

Q: You obviously focus heavily on maps Tim, why are they so important and what do they tell us about how the world’s changing?

A: All leaders are constrained by geography, with their choices limited by mountains, rivers, seas, and concrete. To follow world events, you need to understand people, ideas, and movements, but if you don’t take geography into consideration, you’ll never have the full picture.

Changes in how the world is mapped provide insight into the dominant political powers of the time. My generation grew up with a world map that had Europe, and more specifically the UK, in the middle. This reflected the mindset of the 16th century when the Mercator projection reflected Europe’s position as the economic, military, and diplomatic centre of the world. But times have changed – and maps now show that centre to have shifted conceptually. Most people would agree that, based on the above criteria, the centre has moved from Europe, with the Indo-Pacific region and the United States and China being the focus of attention.

Q: How pivotal a year do you see 2024 being in geopolitical realignment terms?

A: It’s definitely an interesting year of elections, but also anniversaries. As per the table, we’ve had Taiwan, which didn’t go as China hoped. The outcome for Russia isn’t in question and it will be ‘by how much will Mr Putin win?’ The degree of opposition on the streets will, however, be interesting. It looks likely that Mr Modi will almost certainly win the Indian election. For the EU, the rise of the right and the far right is set to continue. The US is anybody’s guess. In South Africa, the African National Congress is under real pressure and has not yet named an election date. Israel is likely to be a reckoning for Mr Netanyahu. And the UK is looking likely to be in October.

Figure 1: 2024 – a year of elections and anniversaries

| Elections | Anniversaries |

| Taiwan | January 13 | NATO, 75th |

| Russia | March 17 | Kosovo, 25th |

| India | April / May | Russian annexation of Crimea, 10th |

| European Union (EU) | June 6-9 | People’s Republic of China, 75th |

| US | November 3 | |

| South Africa, Israel, UK? | TBC |

On the anniversaries, it’s the 75th for NATO, but 25 years since the high point of NATO and Western power. It’s the 10th anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, based on the first invasion. And matching NATO, it is the 75th anniversary of the formation of the People’s Republic of China. These two anniversaries provide a timely contrast between the two, with NATO (and the multipolar world it represented) a mature force at risk of declining, while the ambition of China becomes ever stronger.

Q: You talk about the world changing from a bipolar to multi-polar model, and potentially now back again. What does this mean?

A: My generation grew up in a bipolar world with 1945-1989 shaped by two world leaders – the US and Russia. The international backdrop was set by the Breton Woods Monetary Conference of 1944 where 44 countries established the World Bank, set the gold standard, and chose the American dollar as the currency of exchange. It was essentially an expression of America’s view of how the world should be. While there were subsequent challenges to this view, it prevailed and in 1989, with the failure of Communism, strengthened further leading us into a unipolar world, with the US at the height of its power. By 2008, this had shifted. Whether following the 9/11 attacks and the American focus on Afghanistan and Iraq, or with the 2008 financial crisis, the dominance of the US weakened, and the multipolar world emerged with new players on the global stage.

Figure 2: Moving back to a bipolar world?

A multipolar world is much harder to understand. In the bipolar world and the Cold War, there were binary choices for countries to make. In the multipolar world it gets more complicated. For example, you’ve got Saudi Arabia free to play China off against America. You’ve got Turkey, a NATO ally and friend, buying its missile defence system from Moscow. There are dozens of examples of this fluidity making a multipolar world complex and difficult to understand. In my view the strength of China and the strength of the US will see us move back to a form of bipolar world, with the re-emergence of a binary choice for countries to make.

Q: How do you view the conflict between Russia and the Ukraine?

A: This is where the maps come in. I don’t argue that geography determines everything, but it is a key factor. In Russia it’s very cold, some of the ports freeze, and to get out to the sea lanes you need icebreakers. Generally, Russia feels hemmed in. There is just one warm-water port, and where is it? It’s in Crimea, annexed by Russia from the Ukraine in 2014.

Figure 3: Geographical importance of Ukraine to Russia

© JP Map Graphics Ltd, taken from Prisoners of Geography by Tim Marshall (Elliott & Thompson, 2015)

Secondly, the narrowest point of the North European plain is Poland. If you want to invade Russia, that’s the route you take. So, when looking westwards Russia seeks to plug that gap. But with the fall of Communism, this plan didn’t work. The fall-back option was to control the flat land in front of it, which is Ukraine and Belarus.

So, what happens next? Ukraine’s on the back foot, they’re running out of munitions and soldiers. Russia has four times as many men, its GDP is close to ten times greater, and it is gearing up to produce (or buy from North Korea) the missiles it needs. At the same time, support for Ukraine is trickling away. If Mr Trump wins the US election he will likely withdraw backing, and support from elsewhere is not enough to sustain the war effort. This could force Ukraine to the negotiation table, at which point the detail of the peace deal will be critical. Will it be a sticking plaster allowing Russia to take the rest of the country in the next 5-10 years? Or will there be security guarantees that allows for investment to rebuild Ukraine?

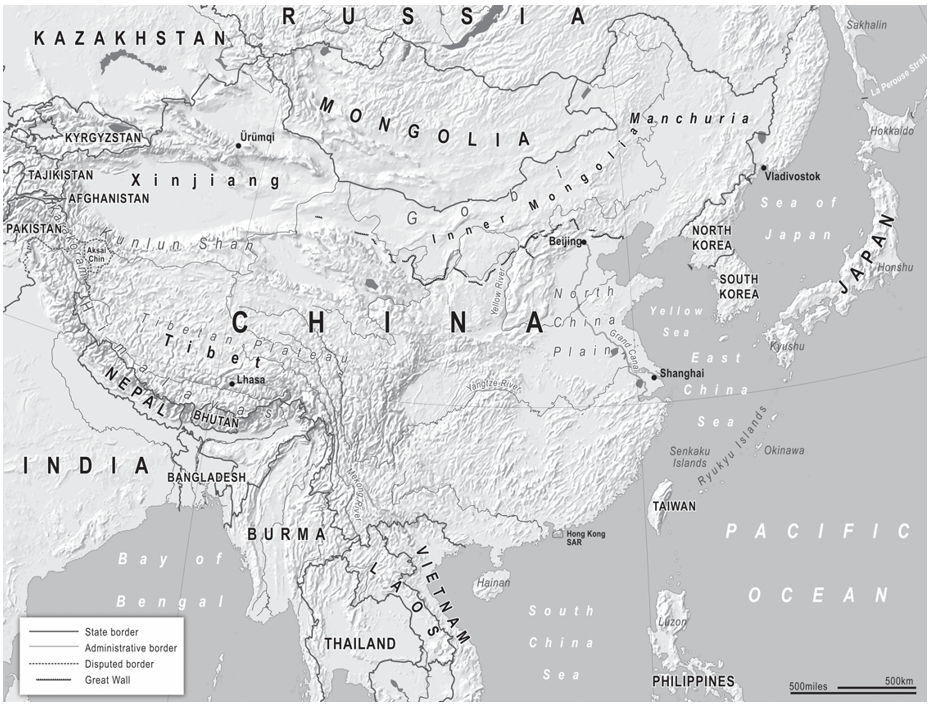

Q: And what role does geography play when it comes to China?

A: From a geographic perspective, China looks eastwards and sees a wall in front of it. America has friends everywhere. Treaty allies allow the Seventh Fleet in the Bay of Tokyo, 30,000-40,000 American troops in Okinawa, Japan, 30,000 American troops in South Korea, Taiwan bristles with American weapons, and the Philippines has recently granted basing rights to the US.

Figure 4: China’s view eastwards and American allies

© JP Map Graphics Ltd, taken from Prisoners of Geography by Tim Marshall (Elliott & Thompson, 2015)

China is an exporting country. It doesn’t matter that no one’s going to blockade it, the fact is they could. Great powers work on what could be and try to turn it to their advantage. So, China has to remove the biggest brick in that wall, Taiwan. They’ve tried diplomatically for years to flip countries’ support, with some success, but that still leaves it without control of Taiwan.

Will China invade Taiwan? I don’t think so this decade. Blockade? Maybe. Taking the Kinmen Islands, which is just off the mainland? Maybe. But to get to the mainland of Taiwan, it’s 120 miles of very rough water. There are only a couple of months a year you could do it. You’d need 400,000 troops, so they would be seen coming two to three months ahead. There are only five landing beaches – so the route is well telegraphed. And you would have to make sure you don’t hit the semiconductor factory in Taipei!

But more than the military considerations, is the economic aspect. There would be a worldwide global recession if there was a proper war in the South China Sea. As an exporting country with declining GDP, economic problems, weakening demographics, and competition from all parts of the globe, why would China risk it? My view is that I don’t think they would.

And would the Americans fight? If they did, it would be a very long war. If they didn’t though, all their allies would fall away. What’s the point of the Philippines or South Korea supporting America if they didn’t fight for Taiwan? They would likely shift allegiances to China, simply because they didn’t have a choice. If America wants to be the dominant power in that part of the Pacific, and the world, they have to support Taiwan. If not, their allies will fall away.

Geopolitical realignment is one of the three macro drivers that we see as meaningfully impacting the investment landscape in the decade ahead. For investors, the shifts will have multiple layers, making it important to assess opportunities though both a macro and a micro lens. Navigating the knock-on effects of cross-border disputes, election results, onshoring, and supply chain adjustments is becoming as important as analyzing companies themselves. With 340+ investment professionals and 90 years’ experience of navigating change, we assess the implications on a daily basis and actively position portfolios for our clients – and their clients – for a brighter investment future.”

Ali Dibadj, Chief Executive Officer