Not too long, not too short – the argument for absolute return

Market inefficiencies will always exist due to imperfect information and unpredictable investor behaviour. Investors can misjudge the prospects for a company; markets can over-react to negative news. This can create opportunities for those investment strategies capable of generating positive returns, whatever the prevailing market conditions.

5 minute read

Key takeaways:

- Valuations on both equities and bonds have been strained, inviting questions as to what alternative strategies investors can use to manage risk across their portfolios.

- Highly accommodative government and central bank policies have pushed the relationship between bonds and equities into uncertain territory.

- The Janus Henderson Absolute Return Fund has been approved for classification as an Article 8 product, reflecting efforts to embed environmental and social considerations into the investment process.

Equity long/short ‘absolute return’ strategies focus on exploiting market inefficiencies to generate absolute returns (ie. a return greater than zero) in various market environments.

The long and short of it

Classic ‘long’ investing involves putting your money into assets (whether that be stocks, bonds or property) in the hopes/expectation that they can rise in value over time. ‘Short’ investing is a form of investment that can profit if the underlying asset falls in value. The most common technique is to borrow an asset (for a fee), and then sell it, with the intention of buying it back for less than you sold it for and returning it to the original owner by the agreed date. If correct, the strategy can make money from assets that are depreciating. But they can lose money if the underlying asset increases in value.

More flexible strategies are also able to actively adjust the proportion of long or short investments held, which can improve their adaptability. Holding a relatively large proportion of long investments can make a strategy more sensitive to prevailing market conditions, indicating optimism about the prospects for stock markets, whereas being net short (holding a greater proportion of shorts than longs), can indicate the expectation that markets might struggle, or that share prices are too high. Net exposure can be adjusted at an overall portfolio level, by sector, region, or even at a stock level, allowing investors to target their exposure in line with their views.

But… why absolute return?

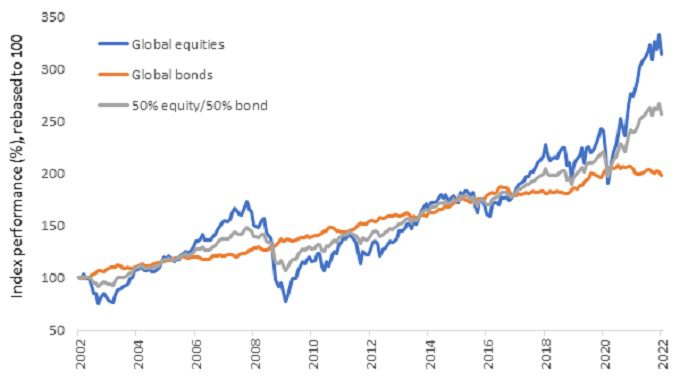

Traditional asset allocation strategies built around equities and bonds have been a useful tool for investors over the past two decades (Exhibit 1) – and this has continued throughout most of the pandemic era. Allocations to bonds helped to mitigate the worst of the market falls seen during that initial period of shock and uncertainty in March 2020. Meanwhile, stock markets rebounded sharply in response to large-scale intervention from central banks and governments to support economies and protect jobs.

Source: Refinitiv Datastream, 31 December 2002 to 31 January 2022. Rebased to 100 at start date. Past performance does not predict future returns.

Note: ‘Global equities’ is the MSCI World Total Return Index (in US dollars). ‘Global bonds’ is the JPM GBI Global All Traded Index. ‘50% equity/50% bond’ represents a simple 50/50 strategy equally allocated to equities and government bonds.

November 2020 was a significant moment, with markets responding positively to news of Pfizer’s vaccine breakthrough, optimism that continued throughout most of 2021, despite the uncertainty created by emergent strains with different transmissibility and potency. This has left both equities and bonds currently looking arguably expensive. This, in turn, is leading investors to seek alternative strategies investors that can help them better manage risk across their portfolios.

Could traditional diversification strategies fail to protect clients in the next downturn?

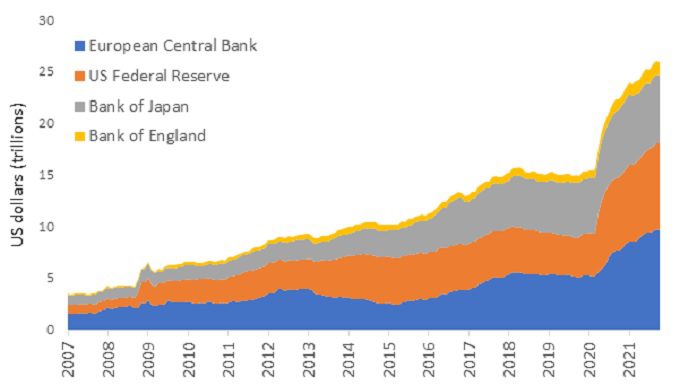

History shows us that diversification is not something that should be taken for granted. Governments and central banks have pursued highly accommodative policies, which has pushed the relationship between bonds and equities into uncertain territory. For the world’s major central banks, the purchase of massive quantities of government bonds (and other assets), aimed at increasing economic activity, has led to significant increases in the size of their balance sheets (Exhibit 2).

While this largesse helped to finance governments during the pandemic, it has also helped to inflate asset prices. Central banks now face the high-stakes task of finding some way to unwind their stimulus measures (‘tapering’), without precipitating a new crisis. The US Federal Reserve has been the first major central bank to act, dialling back its bond purchases from $120 billion per month in November 2021, with the intention of ending them by March 2022. Elsewhere, in late 2021 the Bank of England surprised markets by increasing interest rates for the first time since 2018. Markets have reacted negatively to this surprisingly hawkish stance, with both equities and bonds[1] losing ground in January 2022.

Products that meet the needs for modern investors

Demand continues to grow for long/short equity strategies as the correlation between stocks continues to fall from the peak we saw during the early days of the pandemic. The past few months has also seen a rotation from growth to value, supported by rising interest rates and higher-than-expected inflationary pressures. This is likely to be a more favourable environment for absolute return strategies where stock selection is based on company fundamentals, as is the case with our Janus Henderson Absolute Return Fund.

Finally, we are also celebrating confirmation that the Janus Henderson Absolute Return Fund has been approved for classification as an Article 8 fund, effective from 25th February 2022. This was positive recognition of our efforts to embed environmental and social considerations in our investment process. In accordance with the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), Article 8 labelled portfolios promote, among other characteristics, environmental and social characteristics.

Queste sono le opinioni dell'autore al momento della pubblicazione e possono differire da quelle di altri individui/team di Janus Henderson Investors. I riferimenti a singoli titoli non costituiscono una raccomandazione all'acquisto, alla vendita o alla detenzione di un titolo, di una strategia d'investimento o di un settore di mercato e non devono essere considerati redditizi. Janus Henderson Investors, le sue affiliate o i suoi dipendenti possono avere un’esposizione nei titoli citati.

Le performance passate non sono indicative dei rendimenti futuri. Tutti i dati dei rendimenti includono sia il reddito che le plusvalenze o le eventuali perdite ma sono al lordo dei costi delle commissioni dovuti al momento dell'emissione.

Le informazioni contenute in questo articolo non devono essere intese come una guida all'investimento.

Comunicazione di Marketing.

Important information

Please read the following important information regarding funds related to this article.

- Le Azioni/Quote possono perdere valore rapidamente e normalmente implicano rischi più elevati rispetto alle obbligazioni o agli strumenti del mercato monetario. Di conseguenza il valore del proprio investimento potrebbe diminuire.

- Un Fondo che presenta un’esposizione elevata a un determinato paese o regione geografica comporta un livello maggiore di rischio rispetto a un Fondo più diversificato.

- Il Fondo potrebbe usare derivati al fine di conseguire il suo obiettivo d'investimento. Ciò potrebbe determinare una "leva", che potrebbe amplificare i risultati dell'investimento, e le perdite o i guadagni per il Fondo potrebbero superare il costo del derivato. I derivati comportano rischi aggiuntivi, in particolare il rischio che la controparte del derivato non adempia ai suoi obblighi contrattuali.

- Qualora il Fondo detenga attività in valute diverse da quella di base del Fondo o l'investitore detenga azioni o quote in un'altra valuta (a meno che non siano "coperte"), il valore dell'investimento potrebbe subire le oscillazioni del tasso di cambio.

- Se il Fondo, o una sua classe di azioni con copertura, intende attenuare le fluttuazioni del tasso di cambio tra una valuta e la valuta di base, la stessa strategia di copertura potrebbe generare un effetto positivo o negativo sul valore del Fondo, a causa delle differenze di tasso d’interesse a breve termine tra le due valute.

- I titoli del Fondo potrebbero diventare difficili da valutare o da vendere al prezzo e con le tempistiche desiderati, specie in condizioni di mercato estreme con il prezzo delle attività in calo, aumentando il rischio di perdite sull'investimento.

- Il Fondo comporta un elevato livello di attività di acquisto e di vendita e pertanto sosterrà un livello più elevato di costi di operazione rispetto ad un fondo che negozia con meno frequenza. I suddetti costi di operazione si sommano alle spese correnti del Fondo

- Il Fondo potrebbe perdere denaro se una controparte con la quale il Fondo effettua scambi non fosse più intenzionata ad adempiere ai propri obblighi, o a causa di un errore o di un ritardo nei processi operativi o di una negligenza di un fornitore terzo.