JH Explorer in Tunisia: Sailing through rough seas

Portfolio Manager Sorin Pirău from the Emerging Markets Debt Hard Currency Team highlights the key takeaways from his recent trip to Tunisia.

9 minute read

Key takeaways:

- President Kais Saied and his appointed government have the ability to improve governability and deliver on a reform agenda. Whether they will do so is a different question; one which will decide Tunisia’s economic fate over the medium term.

- Recent easing of the massive pressure on Tunisia’s public and external finances means the government can delay subsidy reform ahead of the 2024 presidential election. Over the short term, the country has many options to fund itself, either by reviving its stalled International Monetary Fund programme or by leveraging its geopolitical position to attract further donor inflows.

- Tunisia’s deal with the EU to fight illegal migration in return for financial support underscores the country’s geopolitical leverage, but it also creates a moral hazard for the country; one that clouds the outlook for bold reforms and tough policy adjustments in the near future.

| The JH Explorer series follows our investment teams across the globe and shares their on-the-ground research at a country and company level. |

On our way back home from attending the IMF Annual Meetings in Morocco, we paid a visit to Tunisia, a country that is not on every emerging market debt investor’s radar due to its benchmark weight of less than 0.12%.1 However, this small nation, which is considered the birthplace of the Arab Spring, cannot be overlooked if one wants to understand the major trends shaping the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

Across many countries in the MENA region, the tortuous road to democracy – one involving authoritarian backlashes and civil strife – has also shaped relationships with outside powers like the EU and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), all of whom are trying to achieve their own strategic objectives, such as limiting migration flows or maintaining regional stability and security.

With that in mind, we went to Tunis wanting to understand if market fears of an imminent restructuring were justified, or whether the various factions in Tunisian society would once again be able to forge a peaceful consensus on how to escape the economic malaise that had gripped the country.

IMF bailout: on ice for now, but there for a rainy day

In the closing months of 2022, the Tunisian economy looked to be heading towards a brick wall. The government had negotiated a $1.9bn bailout programme with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), intended to stabilise fiscal and external balances through a comprehensive public sector wage reform and an effort to restrain fuel subsidies and limit contingent liabilities stemming from SOEs. However, due to a delay in receiving financing assurances from Tunisia’s bilateral partners (which only came in the first quarter of 2023) and the government stalling on the adjustment of petrol prices, the programme never went to the IMF Board for final approval.

As expected, this led to a significant weakening of Tunisian sovereign bond prices in the first four months of 2023. During this period, the 2026 maturity briefly traded below 50 cents on the dollar and the October 2023 maturity dropped below 85 cents on the dollar, reflecting market fears that a restructuring was imminent.

What ultimately saved the day was a combination of two factors: external support and better-than-expected performance of macro fundamentals. The World Bank, the EU, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Japan, the African Export-Import Bank and others provided much needed stopgap funding, with only some of this help (like the EU’s €900m Macro-Financial Assistance) contingent on an IMF programme. Even better, the current account deficit (CAD) outperformed the IMF projections of 7.2% of GDP by more than 3 percentage points, thanks to strong export growth, tourism receipts and remittances.2

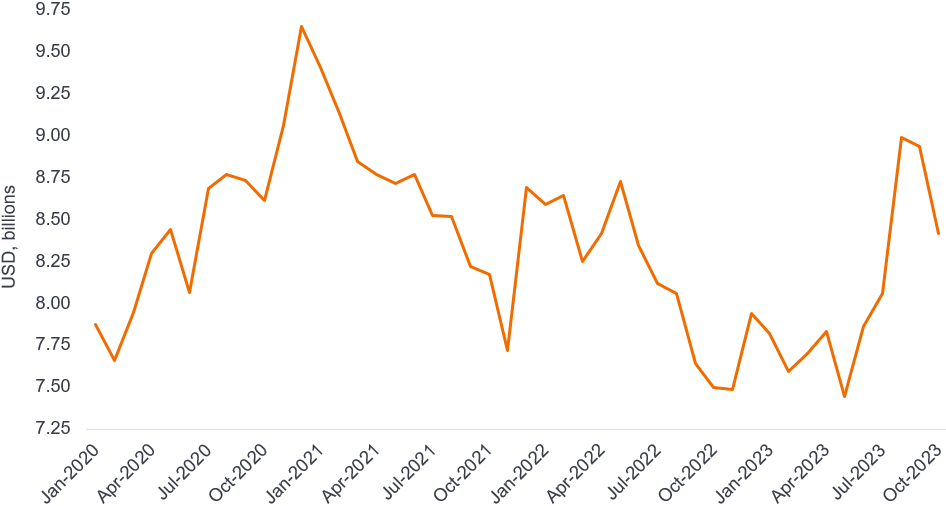

Taken together, this led to a strengthening of foreign exchange (FX) reserves, which touched $8.4bn ahead of the €500m October 31st Eurobond maturity, which was repaid in full after our trip. Figure 1 shows the resilience of Tunisia’s FX reserves despite fears earlier in 2023 that they would suffer a sharp decline.

Figure 1: Tunisia’s gross international reserves

Source: Janus Henderson Investors and Macrobond. Data as at 1 October 2023.

The economy’s external resilience has provided the government with the “luxury” of treating the IMF programme like an option of last resort: something that can be avoided if the economy continues to overperform, yet a useful backstop in case of a crisis. Currently, the programme can best be described as “suspended until further notice”.

Wage reforms progressing, but subsidy bill remains a bone of contention

During our discussions in Tunis with various multilateral institutions, local banks, foreign embassies and government authorities, it was encouraging to hear that some critical parts of the reform agenda agreed back in October 2022 were already being implemented. Key among these is the wage bill reform, a set of measures agreed in the summer of 2022 with the Nobel prize winning trade union UGTT, aimed at reining in the country’s ballooning wage bill through a combination of a recruitment freeze, early retirement schemes and an audit of State-Owned Enterprise (SOE) employees.3

The major bone of contention with the IMF remains the subsidy bill, which at 7% of GDP remains one of the highest in our investment coverage universe. Subsidies have recently become a subject of totemic significance after President Saied publicly expressed his opposition to cutting any subsidies for fuel, electricity and food.

The Central Bank of Tunisia will drive the country’s efforts to navigate a tough 2024 and any attempts to undermine its credibility and independence will likely be taxed by investors and the international community.

Nevertheless, the prevailing view on the ground was that after the upcoming presidential elections scheduled for the autumn of 2024, there will be room for compromise, as the president is likely to moderate his opposition if compensatory measures are put in place to protect the poor and the IMF allows for a more gradual adjustment of energy prices.4 The upcoming Article IV mission in December 2023 (which was recently postponed for early 2024) was highlighted to us as one possible avenue to restart discussions with the Fund. The publication of the related IMF report, scheduled for the first quarter of 2024 and which should contain an updated Debt Sustainability Analysis and set of macroeconomic forecasts, will be eagerly awaited by investors.5

Volatile local political environment

In July 2021, President Saied initiated a so-called “self-coup” by firing the prime minister, suspending parliament and assuming all executive power. Since then, the country has been in a continuous state of political flux. A constitutional referendum expanding the president’s power and fresh parliamentary elections held in December 2022 were boycotted by a large part of the population who had become disillusioned by their first decade of democratic experience.

The president’s authoritarian tendencies have put off some voters, but he remains by far the most popular politician in the country, despite his handling of the ongoing cost of living crisis and penchant for political repression.

The dismissal early in 2023 of four ministers followed by the sacking in August 2023 of Najla Bouden, the Arab world’s first female prime minister, and the firing in October 2023 of Economy Minister Samir Saied, an ardent supporter of the IMF programme who was ousted hours before we landed in Tunis, highlights the volatile policy environment and the degree of control the president currently exerts in the domestic political sphere.

Geopolitics trump domestic politics

That said, local politics tend to be relegated to the backseat when geopolitical concerns take centre stage. This was clearly on display earlier in the summer of 2023 when – despite the president’s dismantling of state institutions and wave of arrests targeting politicians, civil society activists, trade unionists, judges and journalists – the EU was willing to overlook the country’s democratic recession in a quest to fulfil its own strategic objective of limiting irregular migration flows over the Mediterranean Sea.

The “Strategic Partnership Agreement” signed in July 2023 saw Tunisia committing to cooperate on the fight against the smuggling and trafficking of migrants in exchange for financial aid.6 The deal had a rocky start, with Tunisia returning €60m in October as a sign of dissatisfaction with the European Commission’s insistence that the bulk of the aid package should only be disbursed in conjunction with an IMF programme.

However, the expectation in Tunis was that given the importance attached to the migration issue by many European states a solution may be found, perhaps after the European Parliament elections in the Spring of 2024, through which some of the financial aid could be delinked from an IMF programme or the Fund could be convinced to take a more “pragmatic” approach in its negotiations. Whether or not this can be achieved remains to be seen, but in our view the manner in which Tunisia decides to play its geopolitical cards in 2024 will be a key credit risk driver and something we will be monitoring closely.

Summing up

For better or worse, the political fragmentation and policy paralysis that characterised Tunisia’s credit story for the past decade is history. The president and his appointed government have the ability to improve governability and deliver on a reform agenda, a break from past form that saw two IMF programmes failing due to poor implementation. Whether he has the willingness to do so, is an entirely different question and something that will drive Tunisia’s economic fate over the medium term.

A better macro performance has allowed the government to delay subsidy reform and push the IMF programme into 2024. Supported by bilateral and multilateral funding, President Saied will only engage with the IMF under his own terms and with an eye on the upcoming elections.

Over the short term, the country has many options to fund itself, either by reviving its stalled IMF programme, or by leveraging its geopolitical position to attract further donor inflows. The country’s unexpected external performance in 2023 leaves it in a favourable position to meet its upcoming Eurobond maturities in February 2024 and January 2025 absent any major external or domestic shock.

The migration issue will keep EU countries involved and willing to help as long as Tunisia remains engaged. In our view, Tunisia will continue to play up its geopolitical significance particularly in its relationship with the European Union, with whom it had recently signed a “Strategic Partnership” deal to fight illegal migration in return for financial support. The moral hazard this creates means that the outlook for bold reforms and tough policy adjustments in the near future is rather dim.

1 Tunisia’s weight in the benchmark JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified (EMBIGD) as of 31 October 2023. EMBIGD tracks liquid US dollar emerging market fixed and floating-rate debt instruments issued by sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities and is a widely followed benchmark. Tunisia – besides its benchmark $1bn maturity in 2025 – also has two EUR-denominated bonds outstanding (€850m maturing in February 2024 and €700m maturing in July 2026). Its July 2026 EUR-bond is included in the EURO EMBIGD benchmark.

2 As of November 2023, Central Bank of Tunisia projects the CAD for 2023 to come in at “slightly above 4%”.

3 Four Tunisian organizations, the UGTT, the Tunisian Confederation of Industry, Trade and Handicrafts, the Tunisian Human Rights League, and the Tunisian Order of Lawyers received the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize for their achievement of an “alternative peaceful political process in 2013 when the country was on the brink of civil war and subsequently guaranteed fundamental rights for the entire population”. In 2022, public sector wages and salaries accounted for 14.7% of GDP, one of the highest levels in the world.

4 The IMF programme focuses mainly on reining in energy subsidies (electricity and fuel) which are much more regressive than food subsidies, vastly favouring the car-and energy-consuming parts of the population, that are the least in need for help.

5 Under Article IV of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement, the IMF holds bilateral discussions with members, usually every year. A staff team visits the country, collects economic and financial information, and discusses with officials the country’s economic developments and policies.

6 The financial package consisted of €900m in macro-economic support contingent on an IMF programme and a further €150m in budgetary support and €105m earmarked for improving the country’s border control capabilities.

UGTT: The Union Générale Tunisienne du Travail (UGTT) – or Tunisian General Labour Union – has a membership of more than one million and has historically been viewed as an umbrella for social movements in Tunisia. In recent years, the UGTT has worked together with Tunisian Human Rights League-LTDH, the Tunisian Confederation of Industry, the Trade and Handicrafts-UTICA and the Tunisian Order of Lawyers. Collectively labelled the National Dialogue Quartet, they received the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize for their contribution to the building of a pluralistic democracy in Tunisia.

State-owned Enterprise (SOE): A legal entity created by a government with a view to participating in commercial activities on the government’s behalf.

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC): A political and economic alliance of six Middle Eastern countries—Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, and Oman – established in 1981. The aim of the GCC is to achieve unity among its members based on their common objectives and similar political and cultural identities.

African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank): Afreximbank, headquartered in Cairo, was established in 1993 with the purpose of financing, promoting and expanding intra-African and extra-African trade.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF): The IMF is a global organization that works to achieve sustainable growth and prosperity for all its 190 member countries. It does so by supporting economic policies that promote financial stability and monetary cooperation, which are essential to increase productivity, job creation and economic well-being. The IMF is governed by and accountable to its member countries.

Monetary policy: The policies of a central bank, aimed at influencing the level of inflation and growth in an economy. It includes controlling interest rates and the supply of money. Monetary stimulus refers to a central bank increasing the supply of money and lowering borrowing costs. Monetary tightening refers to central bank activity aimed at curbing inflation and slowing down growth in the economy by raising interest rates and reducing the supply of money.

GDP: The value of all finished goods and services produced by a country, within a specific time period (usually quarterly or annually). It is usually expressed as a percentage comparison to a previous time period and is a broad measure of a country’s overall economic activity.

Current account deficit: A current account deficit (CAD) exists when the value of goods and services imported by a country exceeds the value of the goods and services that it exports.

The World Bank: The World Bank plays a key role in the global effort to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity. Working in more than 100 countries, the World Bank provides financing, advice and other solutions that enable countries to address the most urgent challenges of development.

Eurobond: A bond denominated in a currency not native to the country where it is issued.

Article IV Consultation: A regular, usually annual, comprehensive discussion between the IMF staff and representatives of individual member countries concerning the member’s economic and financial policies. The basis for these discussions is in Article IV of the IMF Articles of Agreement (as amended, effective 1978) which direct the Fund to exercise firm surveillance over each member’s exchange rate policies.

Volatility: This measures risk using the dispersion of returns for a given investment. The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index moves up and down.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

There is no guarantee that past trends will continue, or forecasts will be realised.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

High-yield or “junk” bonds involve a greater risk of default and price volatility and can experience sudden and sharp price swings.

Beta measures the volatility of a security or portfolio relative to an index. Less than one means lower volatility than the index; more than one means greater volatility.

These are the views of the author at the time of publication and may differ from the views of other individuals/teams at Janus Henderson Investors. References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable. Janus Henderson Investors, its affiliated advisor, or its employees, may have a position in the securities mentioned.

Past performance does not predict future returns. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested.

The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation.

Marketing Communication.