The credit market, which has been tightening and benefitting from positive market technicals (demand and supply for bonds) over the past several years, has seen a recent change in dynamics. While hyperscalers (Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, and now Oracle) funded much of their capital expenditure (capex) outlays in 2025 with free cash flow from their core businesses, September saw a noted shift in issuer behaviour as hyperscalers all moved to raise capital externally. Moreover, each of the hyperscalers has demonstrated continued momentum and acceleration in their core businesses as of Q3’25, resulting in broader markets granting “permission” for these players to continue their capex spend.

Oracle, Meta, and Alphabet (Google) have led the charge, issuing large amounts of debt to finance their artificial intelligence (AI) ambitions, and accomplishing these debt issuances at sub-5% weighted average interest rates.

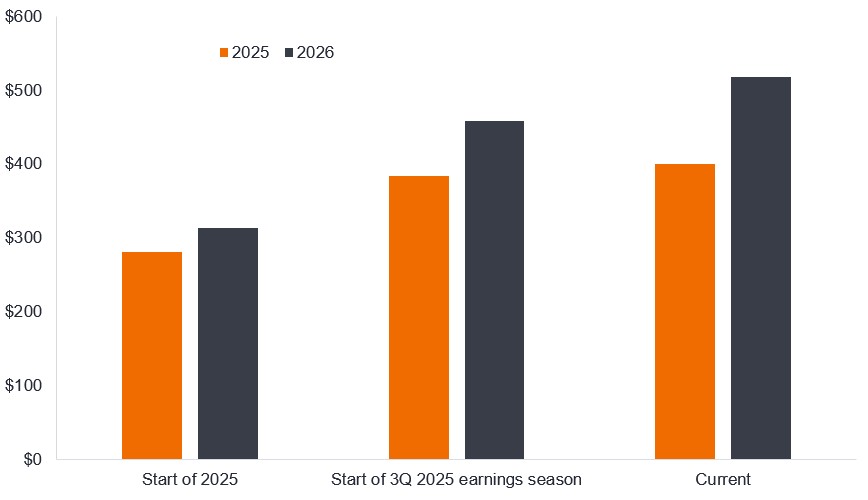

As shown in Figure 1, consensus estimates for hyperscaler capex spending in calendar year 2026 have risen from US$314 billion at the start of the year, equating to 12% year-on-year (yoy) growth, to US$458 billion through the start of the Q3’25 earnings season to US$518 billion today, equating to 29% yoy growth.

Consensus capex spending estimates for AI hyperscalers (US$ billion)

AI hyperscalers include Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, Oracle.

Source: Factset, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, 31 October 2025. There is no guarantee that past trends will continue or forecasts will be realised.

‘AI Arms Race’ for leadership

A common refrain is that to win in AI, you must spend big and fast. The leading tech firms perceive a once-in-a-generation opportunity (and threat): in other words, whoever builds the most advanced AI models and platforms could dominate the landscape for years. This dynamic has created a race to scale up computational power, sign long-lived leases on land, and launch unprecedented investments in human capital. While several of the hyperscalers can continue to fund their build-out campaigns with either existing cash on balance sheet or free cash flow generated by their core businesses, they are increasingly looking to public and private debt markets to assist. Much of this mix shift in funding has been driven by the relatively lower cost that debt possesses versus utilising retained earnings or equity.

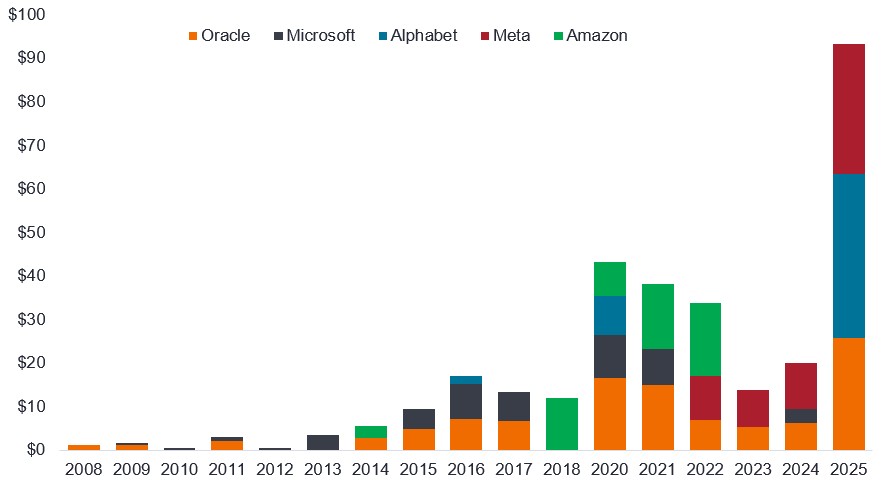

Oracle kicked off the tech issuance frenzy with a blockbuster US$18 billion bond offering, including a rare 40-year tranche priced at 165 basis points (bps) over the corresponding US Treasury. The proceeds are earmarked for cloud infrastructure and partnerships with OpenAI. Meta had “just” US$29 billion of corporate debt at the beginning of October. Since that time, the company has effectively raised another US$57 billion, US$27 billion through the Beignet transaction (a joint venture between Meta and Blue Owl to fund a ~2GW data centre campus in Louisiana that will remain off-balance sheet) and a regular on-balance sheet US$30 billion corporate bond deal. The US$30 billion issuance represented the fifth largest individual bond deal of all time in the investment grade markets, and the largest ever that was not directly used to fund merger and acquisition (M&A) activity. Alphabet followed closely thereafter, issuing €6.5 billion in Europe and US$17.5 billion in the US, effectively growing the debt on its balance sheet by nearly 70% in one day.1

Figure 2: Big Tech issuance (US$ billion)

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, debt issuance in US dollars, 1 January 2008 to 6 November 2025. Note: Meta issuance excludes Beignet deal.

Despite strong fundamentals and investor appetite, Alphabet and Meta paid a clear premium to access the debt market with sizeable new issue premiums (paying an incremental 10-15 basis points as compared to their existing debt).2 The pricing reflects both the scale of their ambitions and the market’s cautious stance on the amount of debt likely coming to the capital markets in 2026 and 2027. In short, while debt is a more attractive financing source for hyperscalers, and credit investors remain willing to fund the AI revolution through numerous vehicles, relative compensation is required.

Scale of issuance: ‘Known unknowns’

Future issuance remains a known unknown: the AI capex super-cycle is expected to continue over the coming years, although the duration and scale remain uncertain, reshaping both the tech sector and many linked industries. In the process, Big Tech’s financial profile is evolving – from cash-rich, asset-light models to capex-heavy, leverage-involved structures that are positioned to make a play for long-term AI leadership. That said, there are several factors working in the hyperscalers’ favour when it comes to managing excessive financing costs: each of them, excluding Oracle, possess stellar credit ratings (AA- or higher)3, and there are a range of novel financing methods outside of traditional channels, including joint ventures and the private markets, though these ancillary financing methods further reduce visibility on future issuance.

Spreads: Tight no more?

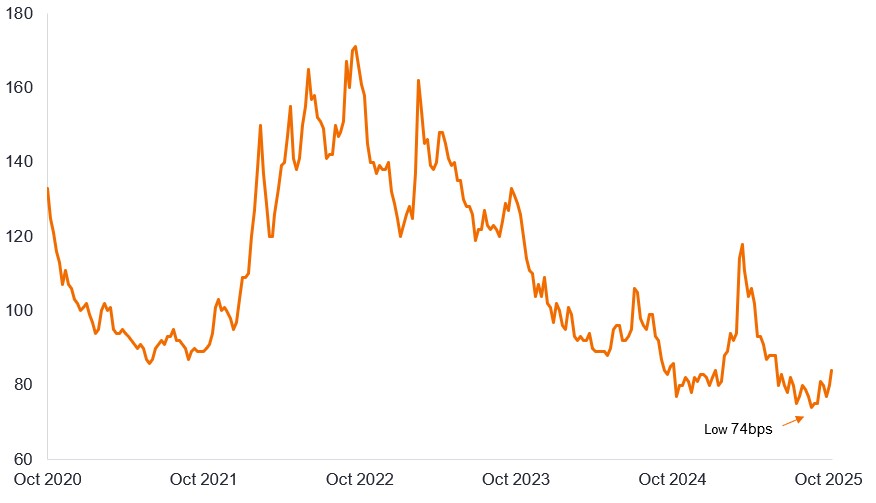

For much of the year, credit spreads have been grinding tighter. US investment-grade spreads touched their narrowest levels in 15 years, with the option-adjusted spread (OAS) falling to 74bps by mid-September.4 But the recent deluge of supply – particularly from tech – may have changed the game.

Figure 3: Average credit spread on US investment grade corporate bonds (basis points)

Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA US Corporate Index, option-adjusted spread over government bonds (Govt OAS), 31 October 2020 to 7 November 2025. One basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point, 1bp = 0.01%Past performance does not predict future returns.

The market’s ability to absorb these large deals, with marketwide spreads only widening by 10bps from their tights by 7 November 2025, is impressive.5 But it is also telling. Investors demanded a premium, and that premium has likely halted further tightening in the technology sector, which has demonstrated strong performance over the last three years.

Credit investors will also likely demand extra compensation until there is clarity around the defined “winners” of this supercycle. Despite the exceptional fundamentals in this cohort, observed through a mix of continued growth and free cash flow generation, we anticipate the shift in financial policy may leave technology spreads range-bound.

These changes are already emerging. In mid-September 2025, 10-year BBB technology spreads traded on average 12bps tighter than broader non-financial corporates; seven weeks later, that premium no longer exists as technology BBBs trade almost in-line with broader non-financial corporates.6

Conclusion: AI debt is reshaping credit markets

The AI arms race is not just a tech equity story – it is a credit story. Oracle, Meta, and Alphabet demonstrate that 1) the credit market currently remains open to large AI capex related funding, but 2) investors are not chasing deals blindly. The premium pricing of recent deals for high-quality issuers suggests a slightly more cautious, selective market. From a fundamental perspective, we believe this is merely a simple matter of supply versus any indication of underlying deterioration in credit quality. These companies are not highly levered and possess strong operating fundamentals and pristine balance sheets.

As we look ahead, the interplay between AI investment, corporate issuance, and credit spreads will remain central. The future may be uncertain, but one thing is clear: Big Tech’s debt binge may have altered the technical picture in credit.

1Source for all deals in paragraph: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, 6 November 2025. Note: According to Morningstar Pitchbook “Meta completes massive, $30b bond deal amid industry-wide AI land grab scramble”, the four other bigger deals were Verizon ($49bn in 2013), Anheuser Busch InBev ($46bn in 2016), CVS Health ($40bn in 2018) and Pfizer ($31bn in 2023).

2Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, 6 November 2025.

3Source: Issuing company websites, credit ratings agencies, correct at 11 November 2025.

4Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA US Corporate Index, Govt OAS, 15 years to 7 November 2025.

5Source: Bloomberg, ICE BofA US Corporate Index, Govt OAS, 19 September 2025 to 7 November 2025.

6Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson Investors, 19 September 2025 to 7 November 2025.

Fixed income securities are subject to interest rate, inflation, credit and default risk. The bond market is volatile. As interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and vice versa. The return of principal is not guaranteed, and prices may decline if an issuer fails to make timely payments or its credit strength weakens.

References made to individual securities do not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector, and should not be assumed to be profitable.

ICE BofA US Corporate Index tracks the performance of US dollar denominated investment grade corporate debt publicly issued in the US domestic market.

Balance sheet:A financial statement that summarises a company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity at a particular point in time.

Basis point:One basis point (bp) equals 1/100 of a percentage point, 1bp = 0.01%.

Callable bond: A bond that can be redeemed or paid off by the issuer prior to the agreed maturity date.

Capex: Money invested to acquire or upgrade fixed assets such as buildings, machinery, equipment, technology, or vehicles in order to maintain or improve operations and foster future growth.

Cash flow: The net balance of cash that moves in and out of a company. Positive cash flow shows more money is moving in than out, while negative cash flow means more money is moving out than into the company.

Cloud computing: The provision of IT services remotely by specialised service providers over the internet.

Corporate bond: A bond issued by a company. Bonds offer a return to investors in the form of periodic payments and the eventual return of the original money invested at issue on the maturity date.

Credit rating: An independent assessment of the creditworthiness of a borrower by a recognised agency such as S&P Global Ratings, Moody’s or Fitch. Standardised scores such as ‘AAA’ (a high credit rating) or ‘B’ (a low credit rating) are used, although other agencies may present their ratings in different formats.

Credit spread: The difference in yield between securities with similar maturity but different credit quality. Widening spreads generally indicate deteriorating creditworthiness of corporate borrowers, and narrowing (tightening) indicate improving.

Default: The failure of a debtor (such as a bond issuer) to pay interest or to return an original amount loaned when due.

Fundamentals: The underlying financial and operational factors, such as profitability, cash flow and management quality, that indicate a company’s ability to meet its financial obligations.

High yield bond: Also known as a sub-investment grade bond, or ‘junk’ bond. These bonds usually carry a higher risk of the issuer defaulting on their payments, so they are typically issued with a higher interest rate (coupon) to compensate for the additional risk.

Hyperscalers: Companies that provide infrastructure for cloud, networking, and internet services at scale.

Inflation: The rate at which prices of goods and services are rising in the economy.

Investment grade bond: A bond typically issued by governments or companies perceived to have a relatively low risk of defaulting on their payments, reflected in the higher rating given to them by credit ratings agencies.

Issuance: The act of making bonds available to investors by the borrowing (issuing) company, typically through a sale of bonds to the public or financial institutions.

Leverage: The ratio of a company’s loan capital (debt) to the value of its ordinary shares (equity).

Maturity: The maturity date of a bond is the date when the principal investment (and any final coupon) is paid to investors. Shorter-dated bonds generally mature within 5 years, medium-term bonds within 5 to 10 years, and longer-dated bonds after 10+ years.

Supercycle: A prolonged period of expansion and above-average growth in a particular market, asset class or sector.

Yield: The level of income on a security over a set period, typically expressed as a percentage rate. For a bond, at its most simple, this is calculated as the coupon payment divided by the current bond price.

Volatility: A measure of risk using the dispersion of returns for a given investment. The rate and extent at which the price of a portfolio, security or index moves up and down.